25 Vascular

AAA

The abdominal aorta is the most common site of an arterial aneurysm. Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are usually located below the renal artery (infrarenal aorta).

The abdominal aorta is 1-3 cm in diameter in most individuals, and a diameter >3 cm at the level of the renal arteries is considered to be an aneurysm. Unlike thoracic aortic aneurysms, an AAA involves all aortal layers and does not create an intimal flap or false lumen. An AAA typically occurs in people aged >60 years and occurs at a higher rate in smokers, men, and people with a history of coronary artery disease.

Pathogenesis

The key pathophysiological event in abdominal aortic aneurysm development is atherosclerosis.

Risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) development include:

Advancing age (esp. >60 years)

Smoking

Hypertension

Family history of AAA

Male sex

Symptoms

Patients typically have few symptoms with AAAs, which are usually incidentally found on screening ultrasound or CT scan of the abdomen. Physical examination can reveal a pulsatile abdominal mass at or above the level of the umbilicus. Once the aneurysm ruptures, only about 50% of the patients survive to come to the hospital. They present with profound hypotension, abdominal or back pain followed by syncope, and possible pulsatile mass on examination. An AAA can rupture into the retroperitoneum and create an aortocaval fistula with the inferior vena cava, leading to venous congestion in retroperitoneal structures (e.g. bladder). The fragile and distended veins in the bladder can rupture and cause gross hematuria (as in this patient).

The symptoms and signs can also mimic other abdominal pathologies, such as renal colic, mesenteric ischemia, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and biliary disease. This patient's acute onset of symptoms, age, and profound hypotension suggest ruptured AAA, which must be ruled out before the other etiologies. He should be immediately taken to the operating room for emergent surgical repair of the ruptured AAA. Mortality with this condition is approximately 50%, so early recognition and operative intervention is essential.

Elderly patients with AAA rupture can present with ECG changes indicating ischemia (e.g. the ST depressions seen in this patient), but profound hypotension and back pain are more concerning for AAA rupture than acute coronary syndrome.

Diagnosis

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) are diagnosed and followed by abdominal ultrasound, which has a near 100% sensitivity and specificity.

The USPSTF recommends a one-time screening for AAA by ultrasonography in men aged 65 to 75 who have ever smoked (currently smoking or have smoked 100 cigarettes or more in the past).

Treatment

Indications for surgical repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) include:

Size at which the risk of rupture exceeds the risk of mortality from the operation repair (greater than 5.5 cm in diameter)

Rapidly increasing size (greater than 0.5 cm in 6 months or greater than 1 cm in a year).

Symptomatic (e.g. abdominal/back/flank pain, limb ischemia)

AAAs can be surgically repaired via open surgery or endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR). All things being equal EVAR has been associated with a lower perioperative (30-day) morbidity and mortality.

Possible complications of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair include:

Renal failure due to atherosclerotic emboli of the renal arteries, contrast (needed in endovascular approach) induced nephropathy, or occlusion of renal arteries with graft placement

Ischemic colitis due to inferior mesenteric artery occlusion by stent-graft placement (abdominal pain, distension, leukocytosis, fever)

Spinal cord ischemia due to disruption of the artery of Adamkiewicz at the T12 level leading to anterior cord syndrome

Bowel ischemia is one known complication (1-7% incidence) of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. It results from inadequate colonic collateral arterial perfusion to the left and sigmoid colon after loss of the inferior mesenteric artery during aortic graft placement. Patients present with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. Fever and leukocytosis may also be present. This adverse effect can be minimized by checking sigmoid colon perfusion following placement of the aortic graft.

Acute Arterial Limb Ischemia

Acute arterial limb ischemia is most often due to arterial embolism and is most commonly seen in the lower extremity compared to the upper extremity.

Two common causes of arterial embolization are atrial thrombi in patients with underlying atrial fibrillation and mural thrombus formation in patients with a recent heart attack.

Symptoms of arterial occlusion (aka the “6 P’s”):

Pain: severe, constant, ischemic rest pain, sudden onset

Pulselessness: unilateral loss of previously palpable pulses distal to the occlusion

Paralysis: reflects the degree of neural or muscle ischemia

Pallor: skin is pale or “cadaveric”

Paresthesias: “pins and needles” feeling that reflects peripheral nerve ischemia

Poikilothermia: skin is cold distal to the occlusion

Reperfusion of the affected limb with thrombolytics or surgery must be accomplished within 6 hours as skeletal muscle can only tolerate this duration of ischemia before becoming necrotic.

Anticoagulation with IV heparin is the first step in treating a patient with suspected acute arterial occlusion. Patients should receive an IV bolus followed by a continuous heparin drip.

Following anticoagulation with heparin, emergent referral for vascular surgical evaluation is required as acute arterial ischemia is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.

Fogarty balloon catheter embolectomy is the surgical procedure of choice in patients with acute arterial limb ischemia.

Fasciotomy should be performed to prevent compartment syndrome which can occur if there is significant edema of the muscle following re-perfusion.

Thoracic Aneurysms

Thoracic aortic aneurysms are usually clinically silent unless a complication such as an aortic dissection or rupture occurs. Less common symptoms include hoarseness from recurrent laryngeal nerve compression and aortic regurgitation from aortic valve stretching.

The majority of ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms are considered degenerative meaning that a combination of genetic and mechanical factors results in cystic medial necrosis which in turn weakens the integrity of the aortic wall.

The major cause of descending thoracic aortic aneurysms is atherosclerosis and its associated risk factors including hypertension, smoking and hypercholesterolemia.

In older patients, hypertension, smoking and hypercholesterolemia are the three most important risk factors for thoracic aneurysm formation with long standing hypertension being the most commonly tested.

Hypertension → hypertrophy of media of vasa vasorum → diminished blood flow to the aortic wall → loss of smooth muscle in aortic media → aortic wall weakens

Younger patients with connective tissue disorders affecting the collagen and/or elastic tissue in the wall of the aorta are especially prone to thoracic aortic aneurysms:

Marfan syndrome

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

Loeys-Dietz syndrome

Defects in copper metabolism

The two major complications from thoracic aneurysm are aortic dissection and hemorrhage.

Syphilis is an important infectious cause of thoracic aortic aneurysms. _Treponema pallidum _invades the vaso vasorum of the ascending and transverse portions of the aortic arch resulting in a weakening of the aortic arch.

Suspect a syphilitic aneurysm in a patient with long standing syphilis and a new diastolic murmur in the right 2nd intercostal space indicating aortic valve insufficiency due to dilation of the aortic valve and valve ring.

Aortic Dissection

A tear in the tunica intima is thought to be the primary event leading to an aortic dissection.

Hypertension is thought to be the most important predisposing risk factor for aortic dissection in patients over 60 years old.

There are several risk factors that predispose patients younger than 40 to aortic dissection:

Connective tissue disorders- Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome

Bicuspid aortic valve

Coarctation

Vasculitis - Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis, rheumatoid arthritis, syphilitic aortitis

Crack cocaine use

The classic presentation of an aortic dissection includes diaphoresis + sudden-onset severe tearing chest pain which radiates to the back between the scapulae and migrates inferiorly as the dissection progresses soon after the onset of the pain.

Unequal pulses in the upper extremities are sometimes observed due to (partial) occlusion of the left subclavian artery or brachiocephalic trunk.

Under systemic pressures, this initial intramural aortic hemorrhage quickly gives rise to an unstable medial hematoma which may:

Proceed proximally toward the heart and into the RCA causing posterior MI (most common coronary vessel implicated in aortic dissection).

Rupture through the adventitia can cause massive hemorrhage (most common cause of death due to aortic dissection).

Rupture into pericardial sac can cause cardiac tamponade.

The Stanford Classification divides aortic dissections into Type A and Type B:

Type A dissections are proximal aortic dissections and must involve the ascending aorta. Type A dissections can have ascending and descending aortic involvement. Type A dissections are the most common and most dangerous.

Type B dissections are limited to the descending aorta ONLY.

Chest x-ray is a common radiograph in patients with suspected aortic dissection who are stable. The most classic finding on chest x-ray in patients with an aortic dissection is a widened mediastinum (sensitive but nonspecific). Other findings include:

Loss of the aortic knob

Tracheal deviation to the right

Calcium sign (displacement of the intimal calcium layer in the aorta)

Chest x-ray is NOT sufficient to make or rule out a diagnosis of aortic dissection. Therefore, CT or transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) are the two preferred radiographic studies due to their accuracy and speed of use. TEE has the added benefit of being able to be performed at bedside, is quicker and exposes the patient to less radiation compared to CT. MRI is most accurate but is not used due to the relatively long time it takes to get results in an emergent situation compared to CT or TEE.

If a dissection is suspected and the patient is unstable, CT, MRI, and angiogram should not be done. In this situation, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is the best confirmatory test that can be used in unstable patients.

Type B dissections are medically managed while Type A dissections are considered medical emergencies and require surgery.

The initial treatment of aortic dissection whether Type A or Type B involves rapid correction of blood pressure using beta blockers (often labetalol) and an afterload reducing agent like clevidipine, nicardipine or nitroprusside.

It is important that beta blockers are given before nicardipine/clevidipine/nitroprusside to prevent reflex tachycardia.

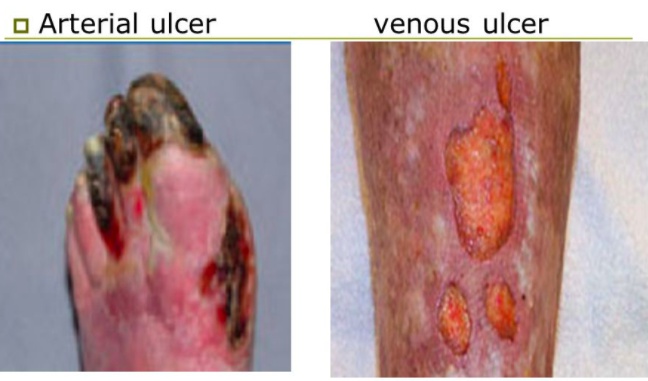

Vascular Ulcers

Venous

Venous ulcers are caused by incompetent venous valves that prevent efficient venous return from the lower extremities. Result in pooling of blood and increased pressure.

This increased pressure damages capillaries causing loss of fluid, plasma proteins and erythrocytes into the tissue. Erythrocyte extravasation causes hemosiderin deposition and the classic coloration of stasis dermatitis. Inflammation of venules and capillaries as well as fibrin deposition and platelet aggregation cause microvascular disease and ultimately ulcerations will occur. Stasis dermatitis most classically involves the medial leg below the knee and above the medial malleolus. Xerosis is the most common early finding; lipodermatosclerosis and ulcerations characterize late disease.

Venous ulceration should be considered when the patient has signs of venous insufficiency including:

Varicose veins

Venous stasis dermatitis - deposition of hemosiderin leading to hyperpigmentation

Heaviness and pain in the legs that decreases with elevation

Edema

lower extremity edema and dermatitis:

Venous stasis ulcers are classically located on the medial aspect of the ankle and calf but can occur anywhere between the ankle and knee. Ulcers on the dorsum of the foot or toes are NOT likely to be venous in origin.

The best initial assessment of venous insufficiency associated with venous stasis ulcers is doppler duplex scan (duplex ultrasound).

Treatment of venous ulcers involves:

Elevation

Compression stockings

Unna's boots - a compression dressing impregnated with zinc oxide to promote healing

Arterial

Arterial ulcers form secondary to occlusive arterial disease and should be suspected in a patient with significant risk factors for peripheral vascular disease such as:

Smoking

Hypertension

High cholesterol

Diabetes

Patients with arterial ulcers will present with symptoms of claudication and leg pain that is worse at night since keeping the legs at heart level will decrease perfusion compared to standing.

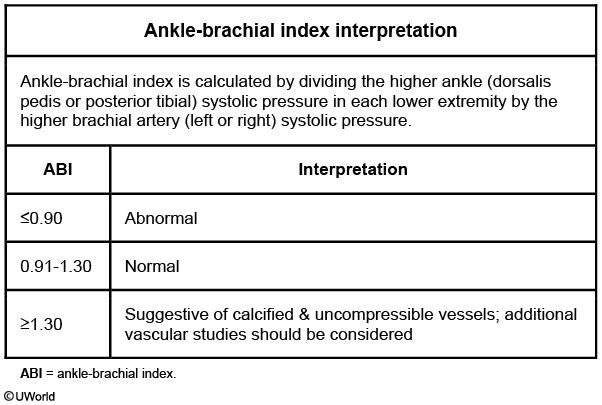

Arterial ulcers are a symptom of advanced peripheral vascular disease (PVD). The first step in working up a patient for PVD with suspected arterial ulcers is taking the Ankle Brachial Index (ABI). For more information on peripheral vascular disease see https://med.firecracker.me/topics/1215.

Unlike venous stasis and diabetic ulcers, arterial ulcers are painful.

Arterial

Venous

Site

Dorsum of toes, feet and ankle,sites of increased pressure

Medial gaiter region (between knee and ankle)

Wound base

Necrotic tissue

Granulation tissue

Appearance

"Punched out"

Shallow, irregular margins

Pain

Painful

Generally painless

DVT

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is the formation of a clot in a large vein, generally of the lower extremity.

Most DVTs occur in veins distal to the popliteal vein, such as in the posterior tibial, though many are asymptomatic. Remember the saphenous vein is a superficial vessel.

Thrombi proximal to the popliteal vein (e.g. femoral or iliac veins), pose a risk of embolization to the lungs. Patients with proximal thrombi often have concomitant pulmonary embolism, though they may not have symptoms of PE.

Virchow’s triad describes the pathophysiological risk factors for venous clot formation:

Venous stasis, such as prolonged immobility or proximal occlusion

Damage to the vascular endothelium

Hypercoagulability, which may be from inflammation, inherited conditions (e.g. Factor V Leiden), pregnancy, cancer, or cigarette smoking

Key elements of the patient’s history that suggest DVT include thrombotic risk factors such as:

Recent surgery (especially orthopedic surgery)

Pregnancy (current or recent)

Cancer

Long-distance plane travel

Prolonged bedrest

Tip: You can remember historical elements as associated with one or more of Virchow’s triad (stasis, endothelial damage, and hypercoagulability.)

While some DVTs are asymptomatic, classic signs and symptoms are unilateral leg pain, swelling, and warmth.

The diagnosis of DVT is most commonly confirmed by compression ultrasound (venous duplex ultrasonography) of the lower extremities. Veins with DVTs will have a non-compressible venous lumen.

In patients with low pre-test probability of DVT, a negative compression ultrasoundor D-dimer excludes the diagnosis.

D-dimer has a high negative predictive value for DVT and is considered comparable to ultrasound in excluding DVT.

In patients with moderate or high pre-test probability of DVT,the false-negative rate of D-dimer increases, and a negative D-dimer is not sufficient to rule out DVT.

In patients with moderate or high pre-test probability of DVT, compression ultrasonography is the best initial test to evaluate patients for DVT before starting anticoagulation.

Starting anticoagulation in a hemodynamically stable patient 48-72 hours after surgery is generally safe and does not significantly increase the risk of bleeding. Inferior vena cava filters can be used in patients in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated (eg, massive gastrointestinal bleed, hemorrhagic stroke).

Unfractionated heparin would generally not be started alone as it is an intravenous medication and needs to be continued until the INR is therapeutic, which can take several days. The goal is to discharge the patient on oral warfarin quickly.

This patient therefore will need to be started on intravenous unfractionated heparin for immediate treatment of the DVT (as it acts quickly) and then on warfarin (typically in the evening of the same day). Heparin is continued for 4-5 days until the INR is at therapeutic levels (goal 2–3).

Both low molecular weight heparin (eg, enoxaparin) and rivaroxaban are not recommended in end-stage renal disease (ESRD); they are metabolized by the kidney, so their use in patients with ESRD is associated with increased bleeding risk. Intravenous unfractionated heparin is not contraindicated in ESRD.

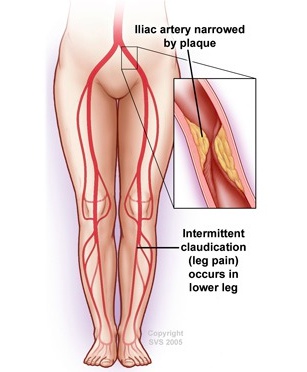

PVD

Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) is the occlusion of the peripheral blood supply secondary to atherosclerosis. See atherosclerosis topic for more details on pathogenesis and risk factors.

Cigarette smoking is by far the strongest risk factor for PVD, even more so than it is for coronary artery disease. Patients with PVD who smoke should be strongly encouraged to stop smoking, as smoking cessation improves symptoms associated with PVD and reduces the rate of associated cardiovascular events.

Many patients with PVD have concomitant coronary or carotid artery disease. Patients with PVD are therefore at markedly higher risk of stroke and ischemic heart disease.

Symptoms

Since peripheral vascular disease is an occlusive disease, symptoms are related to peripheral ischemia, most importantly intermittent claudication, or leg pain with activity that improves with rest, often described as cramping, tightness, or tiredness. Severe disease may cause leg pain even at rest.

Decreased perfusion to the skin results in dry skin, skin ulcers, and loss of hair growth in the affected areas.

The most common site for peripheral artery occlusion or stenosis is in the superficial femoral artery (SFA) at the level of the adductor (Hunter's) canal. Other sites include the popliteal and aortoiliac artery.

Aortoiliac disease may cause erectile dysfunction in addition to buttock and hip claudication.

The patient described is suffering from arterial occlusion at the bifurcation of the aorta into the common iliac arteries (aortoiliac occlusion, Leriche syndrome). Leriche syndrome is characterized by the triad of bilateral hip, thigh and buttock claudication, impotence and symmetric atrophy of the bilateral lower extremities due to chronic ischemia. Impotence is almost always present in men with this condition; in the absence of impotence, an alternate diagnosis should be sought. The pulse is soft or absent bilaterally from the groin distally in this condition. Men with a predisposition for atherosclerosis, such as smokers, are at the greatest risk of this condition. Because impotence is not uncommon in this age group, and the complaints of hip and thigh pain with walking may also be attributed to osteoarthritis, there is a risk of missing this diagnosis if a thorough vascular examination is not performed.

Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosing peripheral artery disease in patients with atypical leg symptoms or claudication is the ankle-brachial index (ABI), the ratio of the systolic blood pressure of the ankle versus that of the arm.

A normal ABI is between 0.9 and 1.3.

An ABI <0.9 is diagnostic for peripheral arterial stenosis and occurs in patients with claudication without resting pain.

An ABI <0.4 is diagnostic for severe peripheral arterial stenosis and occurs in patients with claudication with resting pain.

Patients with an ABI > 1.3 have noncompressible vessels indicative of severe arterial disease from calcified arteries. This is often seen in patients with diabetes and concomitant medial artery calcification.

CT-angiography is the gold standard for locating areas of occlusion in patients with peripheral vascular disease.

Arterial ultrasound of the lower extremities is another noninvasive modality for diagnosing PAD. Arterial duplex ultrasound can be used to localize the site and severity of vascular obstruction. However, it is less sensitive and specific than ABI for the initial diagnosis of PAD. It is generally performed in symptomatic patients with abnormal ABI who are being considered for interventional procedures.

Treatment

The first treatment for PVD is always increased exercise to promote collateral circulation.

Cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, improves walking distance and is approved for treatment of intermittent claudication. Although some sources recommend pentoxifylline, it has not consistently improved walking distance in randomized clinical trials and is not recommended.

Patients who fail lifestyle and medical therapy or who have rest pain (ABI < .4), arterial ulcers, or gangrene should be treated with surgical revascularization with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) with or without stenting OR bypass grafting.

If the limb ischemia is irreversible, amputation is the final treatment.

Varicose Veins

Varicose veins are the most common form of venous disorder of the lower extremity and is the distention of the tortuous superficial veins from incompetent valves in the deep, superficial, or perforator systems. These occur most commonly in the greater saphenous vein and its tributaries, esophagus, anorectum, and scrotum.

The main mechanism by which varicose veins occur is from incompetence of venous valves that cause elongation, dilatation, and tortuosity.

There are multiple risk factors which increase the probability of developing varicose veins including:

Increasing age

Female gender

Oral contraceptives

Pregnancy

DVT

Diagnosis of varicose veins is based on clinical presentation and physical exam findings. Examination will reveal:

Visible long, dilated and tortuous superficial veins along the thigh and leg.

Evidence of venous stasis including ulceration, hyperpigmentation and induration.

Sensation of "heaviness" in the legs.

Patients with varicose veins will have a positive Brodie-Trendelenberg test or Trendelenberg Test (valvular competence test). With patient supine, raise leg and compress saphenous vein at thigh, then have the patient stand; if the veins fill quickly from top down then incompetent valves are present.

The best initial treatment for varicose veins is conservative management consisting of leg elevation and/or elastic compression stockings.

If conservative management fails and/or patients request treatment for cosmetic reasons, the preferred treatment is either injection sclerotherapy or laser ablation rather than surgery for vein ligation and stripping. Careful consideration must be made before ligation is attempted since the saphenous vein may be needed should the patient ever require bypass surgery (CABG).

Superficial thrombophlebitis

Superficial thrombophlebitis is inflammation or thrombosis of a superficial vein that causes pain.

Superficial thrombophlebitis is most often associated with varicose veins in the lower extremity and the site of IV infusion in the upper extremity.

Clinical findings are classically:

Palpable cord

Pain

Mild fever

Treatment for uncomplicated superficial thrombophlebitis is alleviation of symptoms with warm compresses and aspirin for pain relief.

Anticoagulation is NEVER the answer as a treatment option for uncomplicated superficial thrombophlebitis as it is not a risk factor for PE or DVT.

Ischemic Orchitis

This patient likely has ischemic orchitis secondary to damage to or thrombosis of the pampiniform plexus. This is most likely to occur in patients with large or densely adhesed hernia sacs.

Severe pain with the testicle appears to be slightly swollen and very tender to palpation.

The condition is usually self-limited (E), so urgent exploration (B) is not indicated.

Last updated