11 Cardiac Arrest

Cardiac Arrest

Immediate CPR and defibrillation as early as possible are the cornerstones of resuscitation and are the most important factors in determining outcome.

Although the CPR sequence was Airway-Breathing-Compressions (ABCs), it was changed in 2010 to Compressions-Airway-Breathing (CAB) due to evidence that immediate initiation of compressions improved survival.

CPR should be initiated with a compression-to-breath ratio of 30:2. Compressions should be 100-120 bpm (the speed of “Stayin’ Alive”) and approximately 5cm (2”) deep.

Compressing over 120 bpm or leaning on the chest between compressions does not allow adequate ventricular filling and should be avoided.

After intubation, compressions should be performed continuously, and breaths should be given at a rate of 6-10 breaths per minute. ACLS guidelines recommend 10 breaths per minute, but staying on the low end of that is recommended since hyperventilation can lead to increased intrathoracic pressure which decreases venous return and compromises cardiac output.

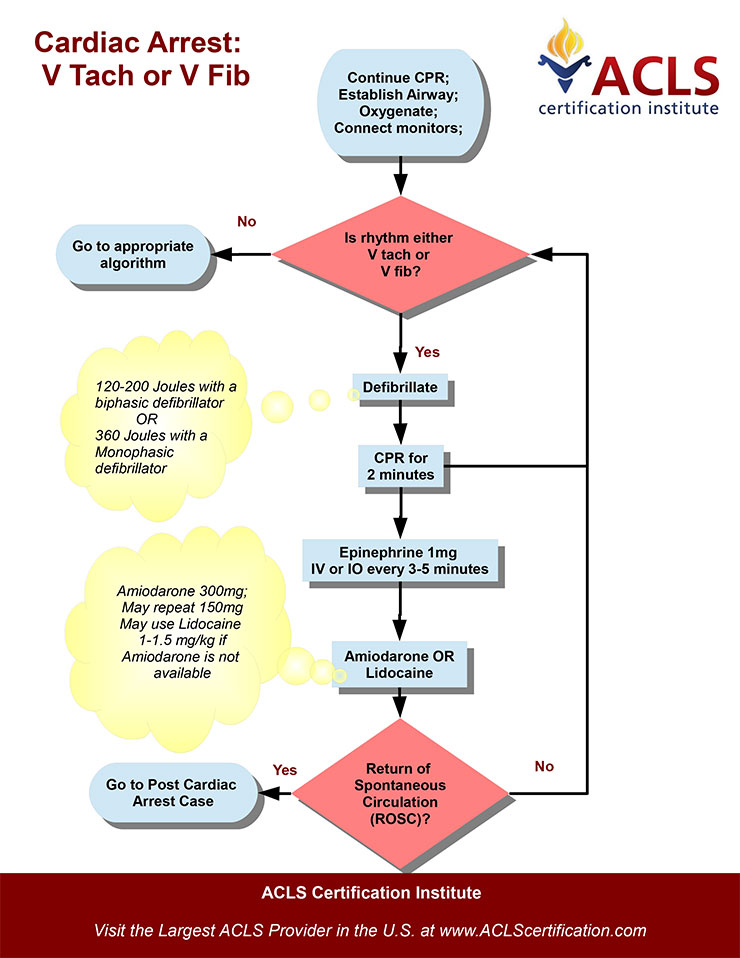

Ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia are the only rhythms that should be defibrillated. Do not shock asystole or pulseless electrical activity.

Airway management in cardiac arrest should focus on maintenance of a patent airway and minimizing interruptions to CPR.

Two advanced methods of airway protection are intubation and supraglottic airway insertion. Intubation is more common, however, some studies have shown supraglottic airways may lead to better survival.

Pharmaceuticals used in ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia cardiac arrest include epinephrine, amiodarone, lidocaine, and magnesium.

All medications in adult cardiac arrest are given at fixed doses, NOT calculated by weight.

Drugs may be given intravenously, intraosseosly, or endotracheally, in that order of preference.

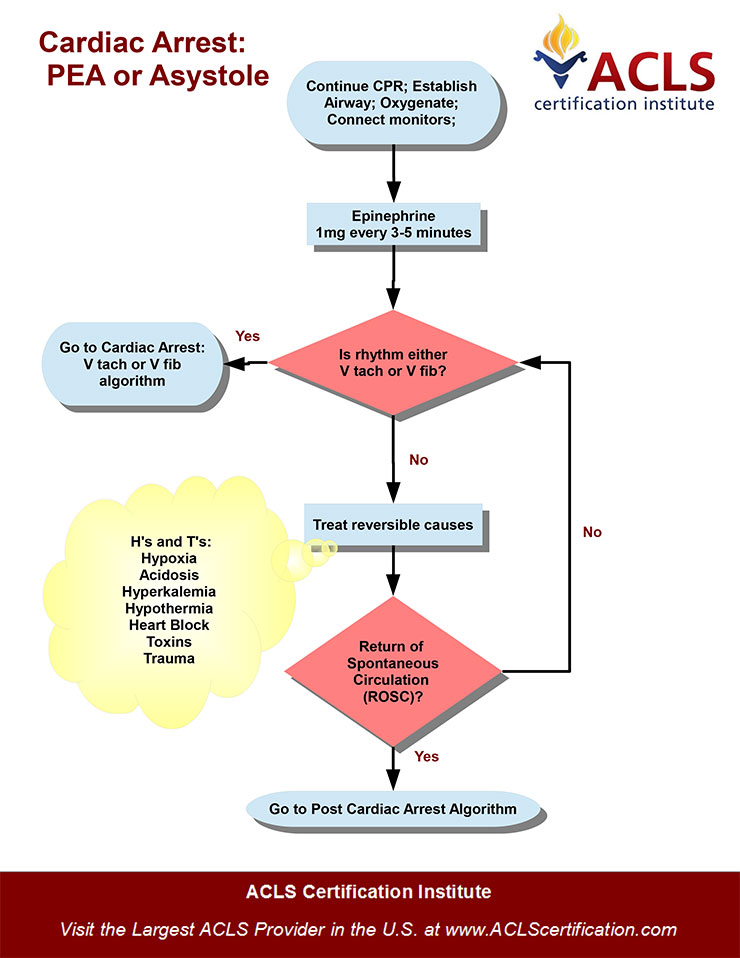

In PEA/asystole cardiac arrest, use only epinephrine.

Atropine is an anticholinergic that is no longer used in PEA/asystole as of the 2010 ACLS guidelines.

Epinephrine is the primary medication used in any cardiac arrest as it is both an inotrope and vasopressor. Dose: 1mg IV/IO every 3-5 minutes. 2-2.5mg can be diluted in 10cc NS and given endotracheally.

Amiodarone is a class III antiarrhythmic used for refractory ventricular fibrillation. Dose: 300mg IV or IO once, followed by a 150mg dose after 3-5 minutes if still indicated.

Lidocaine is a class IB antiarrhythmic that can be given in v. fib/v. tach cardiac arrest if amiodarone fails. Dose: 1-1.5mg/kg IV/IO initially; repeat administration in 5-10 minutes with 0.5 to 0.75 mg/kg IV to a maximum 3 doses or total of 3mg/kg. Use caution when administering lidocaine due to its potentially cardiodepressive toxicity.

Magnesium is given for torsades de pointes because it decreases calcium influx into the myocardium. Dose: 1-2g slowly (30-60seconds) IV/IO initially. Repeat dose in 5-15min.

Note: Vasopressin was removed from the treatment algorithm in the 2015 ACLS update.

Approach

Cardiac arrest is the failure of effective heart contractions. In other words, the absence of a pulse.

There are many causes of cardiac arrest. Some of the most common are listed here by organ system with examples:

Cardiac: myocardial infarction, valve dysfunction

Pulmonary: primary respiratory failure, airway obstruction, pulmonary embolus

Metabolic: hypo/hyperkalemia, hypo/hypermagnesemia, hypo/hyperglycemia

Toxic: digoxin, calcium channel blockers, cocaine, heroin, carbon monoxide

Environmental: hypothermia, drowning, electrocution

The 6 Hs and Ts mnemonic is commonly used to remember potentially reversible causes of cardiac arrest:

Hypoxia

Hypothermia

Hypovolemia

Hypo/hyperkalemia

Hypo/hyperglycemia

Hydrogen ions (acidosis)

Toxins (drug overdoses)

Tension pneumothorax

Tamponade

Thrombosis (myocardial infarction)

Thromboembolism (pulmonary embolism)

Trauma

Cardiopulmonary arrest is defined by the triad of apnea, pulselessness, and loss of consciousness.

The pulse should always be assessed in a large artery, e.g. carotid or femoral.

Breathing is assessed by checking for airway patency and looking, listening, and feeling for spontaneous breathing.

Loss of consciousness occurs within 15 seconds of cardiac arrest. Pupils will dilate within 1 minute of arrest, but will constrict with immediate, properly performed CPR. Some patients may briefly seize.

Primary respiratory arrest will result in transient tachycardia and hypertension, which then progresses to loss of consciousness, bradycardia, and finally pulselessness.

After several hours, dependent lividity and rigor mortis may occur. In days, the body will begin to rot and liquify. Temperature does not begin to decrease until many hours after arrest and is a poor initial indicator of time since arrest; in addition, hypothermia may cause cardiac arrest. Resuscitation should not be attempted in these patients.

The history and physical exam in cardiac arrest focus on determining a probable cause and prognosis.

History should include whether the arrest was witnessed, time of initial CPR, possibility of drug ingestions, initial ECG rhythm, and any interventions by EMS providers. Other important information includes baseline health status, previous end-organ disease, malignancy, infection, hemorrhage, or risk factors for CAD and pulmonary embolism.

Physical exam is extremely focused on the following:

Assessing the adequacy of the airway and ventilation

Confirm the diagnosis of cardiac arrest

Find evidence of a cause

Assess for complications of interventions

Monitoring during CPR includes a minimum of assessing large-vessel pulse for effective compressions. In the presence of a defibrillator, the patient should be assessed for a shockable rhythm every 2 minutes of CPR.

Since successful resuscitation ultimately depends on adequate coronary perfusion, assessment of the coronary perfusion pressure can be achieved with indwelling arterial and venous pressure catheters. An indwelling arterial pressure catheter alone can provide an estimate of diastolic pressure and improve the effectiveness of CPR. However, these techniques are rarely available in a primary cardiac arrest.

End-tidal CO2 measured after endotracheal intubation correlates with coronary perfusion pressure and cerebral perfusion. Since end-tidal CO2 is quick and relatively available, it is the one of the most common ways to monitor adequacy of CPR and return of spontaneous circulation in the emergency department.Note: When minute ventilation and CO2 are held constant (i.e., no NaHCO3 is given), only increased cardiac output or return of spontaneous circulation will increase end-tidal CO2.

Echocardiography may be used to assess prognosis. Patients found to have cardiac wall motion are much more likely to achieve return of spontaneous circulation than patients without cardiac wall motion.

Laboratory tests, with the exception of bedside blood glucose, are not often available fast enough to aid in treatment.

Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is defined as restoration of cardiac function. In contrast, successful resuscitation is defined by return of normal brain function.

Pharmaceuticals used in cardiac arrest include epinephrine, amiodarone, lidocaine, and magnesium.

Complications after cardiac arrest are caused by the underlying disorder, prolonged ischemia (particularly neurologic complications), or resuscitation (e.g. broken ribs).

Post-cardiac arrest care (after ROSC) is directed towards resolution of the underlying cause of the arrest, maintenance of hemodynamics, and prevention of complications from prolonged global ischemia.

Therapeutic hypothermia improves survival, is neuroprotective and has no absolute contraindications.

An average of 7.9% of EMS-treated cardiac arrest patients survive to hospital discharge.

The most important determinants of outcome are quality of CPR and time to defibrillation.

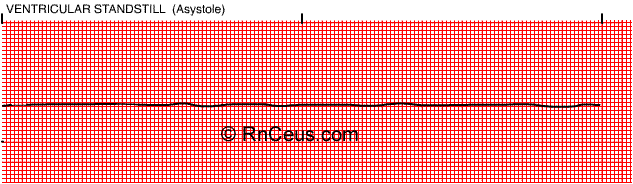

Asystole

Asystole is the absence of electrical and mechanical cardiac activity.

Causes of asystole include:

Primary or secondary cardiac conduction abnormalities

End-tissue hypoxia or metabolic acidosis

Excessive vagal stimulation

Pulseless electrical activity is any ECG rhythm (except VF or VT) without sufficient mechanical contraction to produce a palpable pulse or measurable blood pressure.

Patients with either asystole or pulseless electrical activity need immediate CPR to perfuse their tissues.

In addition to performing CPR and treating any underlying causes of the asystole or pulseless electrical activity, patients should be treated with a vasopressor such as epinephrine.

Defibrillation and synchronized cardioversion have no role in the treatment of patients with asystole or pulseless electrical activity.

Causes of Pulseless Electrical Activity include the 6Hs and the 5Ts.

The 6Hs:

Hypovolemia

Hypoxia

Hydrogen ions (Acidosis)

Hyperkalemia (or hypokalemia)

Hypoglycemia

Hypothermia

The 5Ts:

Toxins (Drugs)

Tamponade

Tension pneumothorax

Thrombosis (Myocardial or Pulmonary Embolism)

Trauma

Last updated