11 Endocrine

Adrenal Insufficiency

Clinical features of primary adrenal insufficiency

Etiology

Autoimmune Infections (eg, tuberculosis, HIV, disseminated fungal) Hemorrhagic infarction Metastatic

Clinical presentation

Fatigue, weakness, anorexia/weight loss, salt craving Gastrointestinal symptoms Postural hypotension Hyperpigmentation or vitiligo Hyponatremia, hyperkalemia May lead to acute adrenal crisis (abdominal pain, shock, fever, altered mental status)

Diagnosis

ACTH, serum cortisol & high-dose (250 µg) ACTH stimulation test Primary adrenal insufficiency: Low cortisol, high ACTH Secondary/tertiary adrenal insufficiency: Low cortisol, low ACTH

Adrenal insufficiency (hypofunction) is a deficiency of adrenal hormones secondary to adrenal or hypothalamic disease.

Causes

Causes include:

Adrenal atrophy or autoimmune destruction

Granulomatous infection (e.g. TB) of the adrenal gland

Infarction of the adrenal gland

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)

Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome (due to adrenal hemorrhage secondary to severe bacterial infection, most commonly Neisseria meningitidis)

DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation)

The adrenal cortex secretes:

Aldosterone (mineralocorticoid)

Cortisol (glucocorticoid)

Androgens (sex steroids)

Adrenal insufficiency may present with symptoms of all three.

Primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease) is failure of the adrenal cortex.

The most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency in the western world is autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex. It is due to autoantibodies against adrenal enzymes that are responsible for corticosteroid synthesis. Autoimmune adrenalitis can occur as an isolated disorder or in association with other autoimmune syndromes (eg, hypothyroidism, vitiligo).

Infiltrative disorders such as tuberculosis (most common cause worldwide) or histoplasmosis are common infective causes of primary adrenal insufficiency. PAI due to tuberculosis (TB) is uncommon in developed countries and typically seen in miliary disease. There is also a high infective rate in AIDS patients. PAI in HIV disease can be due to opportunistic infections (eg, cytomegalovirus, atypical mycobacteria, fungal infections) or inhibition of glucocorticoid synthesis by azole antifungal drugs.

Cancers that commonly metastasize to the adrenal glands and cause primary adrenal insufficiency include:

Lung cancer

Breast cancer

Melanoma

Hemorrhagic adrenal infarction is common post-operatively, in sepsis (frequently in cases of meningococcal sepsis), or in any hypercoagulable state.

Primary

The manifestations of primary adrenal insufficiency are due to decreased aldosterone and cortisol. Findings include:

Hyponatremia (volume contraction → HYPOtension)

Hyperkalemia

Hypoglycemia

Increased skin pigmentation (MSH shares same precursor as ACTH and primary adrenal insufficiency is a hyper-ACTH state)

Eosinophilia and hyperplasia of lymphoid tissue (eg, tonsils) are common but nonspecific findings.

Other symptoms may include constipation, diarrhea, and fatigue.

Hyponatremia and hyperkalemia can be suggestive of primary adrenal insufficiency.

Secondary

Secondary adrenal insufficiency is decreased ACTH from the pituitary due to failure of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, leading to decreased activity of the zona fasciculata and zona reticularis.

Pituitary adenomas are a common cause of suppressed ACTH.

Following long-term suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis with exogenous glucocorticoid therapy (e.g. prednisone), ACTH production is minimal and the adrenal cortex stops producing much endogenous cortisol. Secondary adrenal insufficiency may develop, particularly if the steroids are abruptly stopped.

Metabolism in the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex is NOT controlled by ACTH (it is stimulated by high potassium), so aldosterone is largely unaffected in patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency present with profound hypoglycemia (zona fasciculata) and low testosterone (zona reticularis).

There is no hyperpigmentation in secondary adrenal insufficiency because ACTH is not being produced. Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) is the gene that produces ACTH and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH).

Tertiary

Tertiary adrenal insufficiency is due to decreased corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus.

The most common cause of tertiary adrenal insufficiency is abrupt cessation of high-dose glucocorticoids. It can also be seen in patients with Cushing syndrome in the period following resection of an ACTH or cortisol-secreting tumor.

Diagnosis

The initial evaluation of adrenal insufficiency involves three components:

8 AM serum cortisol

Plasma ACTH levels

ACTH (cosyntropin) stimulation test

Following administration of the synthetic ACTH analog cosyntropin, plasma cortisol levels are measured.

If serum cortisol does not appropriately increase following cosyntropin administration, primary adrenal failure is present.

If serum cortisol is appropriately increased following cosyntropin administration, adrenal function is intact and hypothalamic-pituitary disease is likely.

Primary adrenal insufficiency

Secondary adrenal insufficiency

Elevated ACTH

Decreased ACTH

Low aldosterone

Normal aldosterone

Elevated renin

normal renin

Treatment

Maintenance therapy for patients with primary adrenal insufficiency is glucocorticoids (e.g. hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, or prednisone) as well as mineralocorticoid replacement with fludrocortisone.

Maintenance therapy for patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency is glucocorticoids (e.g. hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, or prednisone).

Note that in contrast to primary adrenal insufficiency, mineralocorticoid replacement is not required in patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Stress dosing (increased doses) of steroids are given in settings of increased stress, such as infection or surgery.

Adrenal Crisis

Shock is the most severe complication of adrenal insufficiency. This is known as adrenal crisis, and should be treated emergently in cases of high clinical suspicion.

Adrenal crisis may be precipitated by stress, such as surgery or sepsis. Suspect it in a patient with chronic illness or known adrenal insufficiency who has refractory hypotension, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia. Patients present with fever, altered mental status, weakness, and vascular collapse.

Treatment requires repletion of adrenal hormones. Patients in adrenal crisis should receive IV fluids, glucose, and corticosteroids (hydrocortisone or dexamethasone) until the shock is reversed.

Adrenal Excess

Pathogenesis

Cushing’s syndrome is a collection of physiologic changes resulting from chronic glucocorticoid excess, known as hypercortisolism. Several things can cause Cushing’s syndrome.

Normally, the hypothalamus produces corticotropin releasing hormone(CRH), which stimulates pituitary release of adrenocorticotropic hormone(ACTH, also called corticotropin). ACTH induces production of cortisol, a glucocorticoid, by the zona fasciculata of the adrenal glands. This is controlled by a negative feedback loop, in which high cortisol levels decrease both CRH and ACTH to prevent further cortisol production.

There are two major types of Cushing’s syndrome: ACTH-independent and ACTH-dependent. These are covered in more detail on their respective sections.

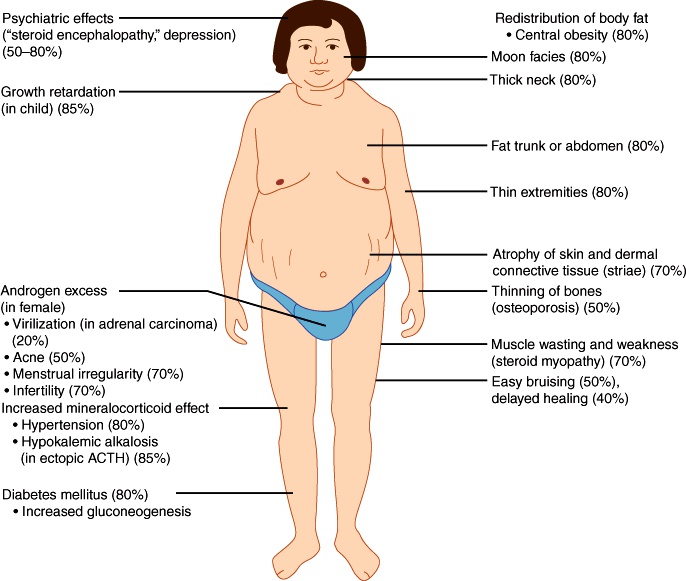

Symptoms

Patients with Cushing’s syndrome classically present with simultaneous development and increasing severity of obesity, glucose intolerance, skin changes, sex hormone imbalances, and osteoporosis. Several lab abnormalities may also be present.

Obesity in Cushing’s syndrome has several unique manifestations:

Central obesity (also called truncal, abdominal, or centripetal obesity)

Facial fat in the cheeks and temporal fossae, causing “moon facies”

Dorsocervical fat pad, causing “buffalo hump”

Supraclavicular fat pad: this is the most specific sign for Cushing’s syndrome

Glucose intolerance in Cushing’s syndrome is caused by the combination of cortisol-stimulated gluconeogenesis and obesity-induced peripheral insulin resistance.

Skin changes include:

Thinning and atrophy, with loss of subcutaneous fat

Easy bruisability, causing difficulty with venipuncture and maintaining IV lines

Abdominal striae, caused by stretching of thin, fragile skin

Hyperpigmentation is seen with excess ACTH, particularly ectopic ACTH

Imbalances in androgens,estrogen, and GnRH cause hirsutism, oily facial skin and acne, libido changes, and menstrual irregularities.

Osteoporosis is caused by reduced calcium absorption in the intestines and kidneys, decreased bone formation, and increased bone resorption.

Diagnosis

Lab abnormalities in Cushing’s syndrome include:

Hypokalemia

Hypercalciuria due to decreased renal calcium resorption

Metabolic alkalosis

Leukocytosis with relative lymphopenia

Hyperglycemia with glucose intolerance

Diagnosis and workup of Cushing’s syndrome involves four major steps:

Rule out exogenous glucocorticoids

Confirm hypercortisolism

Determine if it is ACTH-independent or ACTH-dependent

Localize the source

It is important to ask the patient about exogenous glucocorticoid use that could cause iatrogenic Cushing’s.

Hypercortisolism is confirmed with a minimum of two unequivocally abnormal tests. Tests that may be used include:

Overnight low-dose dexamethasone suppression test: dexamethasone, a glucocorticoid, normally suppresses cortisol production, so morning cortisol following a 1mg dexamethasone injection should be < 1.8 μg/dL. In Cushing’s syndrome, cortisol production is not susceptible to the normal negative feedback system, so morning cortisol following a 1mg dexamethasone injection will be > 1.8 μg/dL.

24-hour urinary free cortisol: abnormal is three times the upper limit of normal (normal value varies by lab). This is often done twice to confirm results.

Late-night salivary cortisol: using saliva or serum, measure the cortisol level in the late evening or at midnight. Normally, cortisol is lowest at this time; elevated levels are suggestive of Cushing’s syndrome. This is often done twice to confirm results.

To determine whether the hypercortisolism is ACTH-independent or ACTH-dependent, plasma ACTH levels are tested.

A low ACTH level, < 5 pg/mL, indicates that the negative feedback loop is intact and the hypercortisolism is due to excess adrenal production of cortisol. This is ACTH-Independent Cushing’s Syndrome.

A high ACTH level, > 10 pg/mL, indicates that the feedback loop is not intact and the hypercortisolism is due to excess ACTH. This is ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome.

A high-dose dexamethasone suppression test after confirming the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome will distinguish between Cushing’s disease and ectopic ACTH syndrome. This is identical to the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test, only with an 8mg dose instead of 1mg. Ectopic ACTH production is not susceptible to any negative feedback regulation, so after a high dose of dexamethasone, cortisol remains high in ectopic ACTH syndrome.

Because ACTH production by the pituitary, even a pituitary tumor, is still relatively susceptible to negative feedback regulation by glucocorticoids, a high dose of dexamethasone will suppress ACTH production in Cushing’s disease and cortisol will be < 5 μg/dL.

Imaging is used to localize the source. This includes:

Brain MRI to look for pituitary adenoma

Chest X-ray or CT to look for small-cell lung cancer

Adrenal CT to look for adrenal malignancy

Complications

Complications of Cushing’s syndrome include:

Diabetes mellitus, since cortisol is diabetogenic

Cardiovascular disease, particularly moderate diastolic hypertension. This is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in Cushing’s syndrome.

Increased risk of venous thromboembolism, possibly due to cortisol-induced increases in clotting factors and serum homocysteine.

Psychologic symptoms, particularly anxiety, depression, and paranoia.

Opportunistic infections, since cortisol causes immunosuppression.

Common opportunistic infections include:

Nocardia

Pneumocystis pneumonia

Cutaneous fungal infections

The major goal of treatment in Cushing’s syndrome is to normalize cortisol levels. Specific treatments vary depending on the cause of hypercortisolism.

After effective therapy, symptoms and signs of Cushing’s syndrome usually disappear gradually over 2-12 months. Patients may never fully return to normal, however, especially regarding psychiatric symptoms, glucose intolerance, hypertension, and osteoporosis.

ACTH Dependent

Pathogenesis

ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome is due to excess glucocorticoid caused by excessive production of ACTH.

Ectopic ACTH syndrome, the second most common cause of Cushing’s syndrome, is caused by production of ACTH by a tumor outside the pituitary.

Ectopic ACTH syndrome is most commonly caused by a small-cell lung carcinoma producing ACTH.

Plasma ACTH levels are increased due to ectopic production. CRH levels are low, due to inhibition by the excess circulating ACTH and cortisol.

Very rarely, Cushing’s syndrome is caused by a CRH-producing tumor. In this case, levels of CRH, ACTH, and cortisol are all increased.

Cushing's Disease

Cushing’s disease is Cushing’s syndrome that is caused by an ACTH-producing pituitary adenoma.

ACTH-producing pituitary adenomas are usually microadenomas.

Plasma ACTH levels are increased due to overproduction by the adenoma. CRH levels are low, due to inhibition by the excess circulating ACTH and cortisol.

Symptoms

Patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome classically present with the constellation of signs seen in hypercortisolism: obesity, glucose intolerance, skin changes, sex hormone imbalances, and osteoporosis. In ectopic ACTH, hyperpigmentation is particularly common. Several lab abnormalities may also be present.

Workup

When hypercortisolism is suspected, workup involves four major steps: rule out exogenous glucocorticoids, confirm hypercortisolism, determine if it is ACTH-independent or ACTH-dependent, and localize the source.

1. Ask about exogenous glucocorticoid use that could cause iatrogenic Cushing’s.

2. Confirm hypercortisolism with a minimum of two unequivocally abnormal tests. This can be done using a 24-hour urinary free cortisol test, a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test, or a late evening cortisol test.

3. Determine whether the hypercortisolism is ACTH-independent or ACTH-dependent by testing plasma ACTH levels.

A low ACTH level, < 5 pg/mL, indicates that the negative feedback loop is intact and the hypercortisolism is due to excess adrenal production of cortisol.

A high ACTH level, > 10 pg/mL, indicates that the feedback loop is not intact and the hypercortisolism is due to excess ACTH. This is ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome.

Some recommend a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test after confirming the diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome to distinguish between Cushing’s disease and ectopic ACTH syndrome. This is identical to the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test, only with an 8mg dose instead of 1mg.

+ Because ACTH production by the pituitary, even a pituitary tumor, is still relatively susceptible to negative feedback regulation by glucocorticoids, a high dose of dexamethasone will suppress ACTH production in Cushing’s disease and cortisol will be < 5 μg/dL. + Ectopic ACTH production is not susceptible to any negative feedback regulation, so after a high dose of dexamethasone, cortisol remains high in ectopic ACTH syndrome.

4. Use imaging to localize the source. In ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism, key studies are:

Pituitary MRI to look for a pituitary adenoma, which would give a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease.

Chest x-ray or CT to look for small-cell lung cancer, the most common cause of ectopic ACTH production.

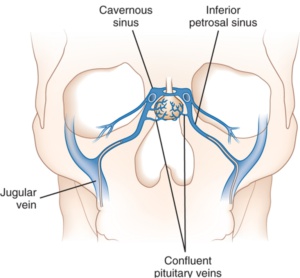

5. If imaging is inconclusive, with bilateral adrenal enlargement or normal pituitary, consider inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS).

The petrosal venous sinus drains blood from the pituitary, so ACTH can be measured there and compared to ACTH levels in the periphery to determine whether the pituitary is overproducing ACTH and causing the hypercortisolism.

This comparison is done both before and after stimulation with CRH (or desmopressin if CRH is unavailable), to provoke maximal release of ACTH.

An ACTH gradient greater from the pituitary suggests a central source, while an ACTH gradient greater from the periphery suggests a peripheral source.

IPSS can also be performed bilaterally to determine which side a pituitary tumor is on; however, this is not typically done since it is expensive, invasive, and not strongly supported in the literature.

Complications of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome are the same as complications in any hypercortisolism condition, and include diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and opportunistic infections.

Treatment

The major goal of treatment in Cushing’s syndrome is to normalize cortisol levels. Specific treatments vary depending on the cause of hypercortisolism.

Ectopic ACTH syndrome is treated with surgical excision of the tumor.

Cushing’s disease (ACTH-producing pituitary adenoma) is treated with transsphenoidal surgery to remove the tumor. In patients for whom fertility is an important concern (such as children under 18), pituitary irradiation can be used rather than surgical excision.

Medical therapy is occasionally used while waiting for surgery or if surgery is not a viable option.

Adrenal enzyme inhibitors are most commonly used to block steroid synthesis. Drug options include ketoconazole (first choice), metyrapone, aminoglutethimide, and etomidate.

Glucocorticoid receptor antagonists or anti-corticotroph tumor drugs (cabergoline or pasireotide) may also be used.

High-dose potassium replacement along with spironolactone to aid in potassium retention, particularly in ectopic ACTH syndrome.

After effective therapy, symptoms and signs of Cushing’s syndrome usually disappear gradually over 2-12 months.

ACTH-Independent Cushing's

Pathogenesis

Cushing’s syndrome is a collection of physiologic changes resulting from chronic glucocorticoid excess, known as hypercortisolism. ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome is due to excess glucocorticoid unrelated to ACTH production, commonly caused by pharmacologic glucocorticoids or adrenal tumors.

Iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome, seldom reported but probably the most common cause, is caused by chronic use of pharmacologic glucocorticoids.

The most common glucocorticoid implicated is prednisone.

Levels of CRH, ACTH, and endogenously-produced cortisol are decreased, because their production is inhibited by high levels of glucocorticoids.

Adrenal tumors, both carcinomas and adenomas, can cause Cushing’s syndrome.

Tumors can produce cortisol independently of ACTH stimulation, leading to excessive endogenous glucocorticoid.

Levels of CRH and ACTH are decreased because their production is inhibited by high levels of cortisol.

Symptoms

Patients with ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome classically present with the constellation of signs seen in hypercortisolism: obesity, glucose intolerance, skin changes, sex hormone imbalances, and osteoporosis. Several lab abnormalities may also be present.

Workup

When hypercortisolism is suspected, workup involves four major steps:

Rule out exogenous glucocorticoids

Confirm hypercortisolism

Determine if it is ACTH-independent or ACTH-dependent

Localize the source

1. Ask about medications to determine if the hypercortisolism could be iatrogenic. Drugs that might cause this include:

Prednisone

Other oral, topical, or inhaled glucocorticoids

Megestrol acetate, a progestin with glucocorticoid activity

Inhaled steroids taken with ritonavir, which can delay their clearance.

2. Confirm hypercortisolism with a minimum of two unequivocally abnormal tests. This can be done using a 24-hour urinary free cortisol test, a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test, or a late evening cortisol test.

3. Determine whether the hypercortisolism is ACTH-independent or ACTH-dependent by testing plasma ACTH levels.

A low ACTH level, < 5 pg/mL, indicates that the negative feedback loop is intact and the hypercortisolism is due to excess adrenal production of cortisol. This is ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome.

A high ACTH level, > 10 pg/mL, indicates that the feedback loop is not intact and the hypercortisolism is due to excess ACTH. This is ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, described in the ACTH-Dependent Cushing’s Syndrome topic.

4. Use imaging to localize the source. In ACTH-independent hypercortisolism, the most important imaging study is an adrenal CT scan with thin-slicing to look for adrenal tumors.

5. If imaging is inconclusive or shows bilateral adrenal enlargement, consider inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS). This is described further in the ACTH-Dependent Cushing’s Syndrome card.

Complications of ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome are the same as complications in any hypercortisolism condition, and include diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and opportunistic infections.

Treatment

The major goal of treatment in Cushing’s syndrome is to normalize cortisol levels. Specific treatments vary depending on the cause of hypercortisolism.

Iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome is treated by gradually weaning the patient off the offending medication. Gradual withdrawal is necessary because most patients who have been on glucocorticoids long enough to cause Cushing’s syndrome will have some level of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis insufficiency on discontinuing the medication.

Adrenal tumors are treated with surgical excision of the tumor.

This is always curative with adenomas.

With carcinomas recurrence is common so irradiation, chemotherapy, or medical therapies are often used in conjunction with surgery.

Medical therapy is occasionally used while waiting for surgery or if surgery is not a viable option.

Adrenal enzyme inhibitors are most commonly used, to block steroid synthesis. Drug options include ketoconazole (first choice), metyrapone, aminoglutethimide, and etomidate.

A medical adrenalectomy can also be accomplished using mitotane if bilateral surgical adrenalectomy is not possible.

After effective therapy, symptoms and signs of Cushing’s syndrome usually disappear gradually over 2-12 months.

Hyperaldosteronism

Hyperaldosteronism is a "catch-all" term referring to a spectrum of disease states related to excess aldosterone production.

Primary

Primary hyperaldosteronism results from overactive production of aldosterone with subsequent suppression of the renin-angiotensin system and low plasma renin levels.

Primary hyperaldosteronism most commonly presents with new hypertension or a further elevation in blood pressure, which is a result of (in order of prevalence):

Idiopathic (bilateral idiopathic hyperaldosteronism, most commonly)

Adenoma

Zona glomerulosa cells becoming reactive to ACTH (very rare!)

Conn syndrome is primary hyperaldosteronism due to an aldosterone-producing adrenal adenoma.

Adrenal adenomas are benign glandular tumors that may produce aldosterone (causing Conn syndrome), cortisol (causing Cushing syndrome), androgens (causing hyperandrogenism), or no hormones at all.

Normally, aldosterone is secreted by the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal gland in response to high Potassium and/or angiotensin II levels. Aldosterone acts on the distal convoluted tubule and collecting duct of the nephron to reabsorb sodium (back into the body) and secrete potassium and hydrogen ions (into the urine).

Therefore, the water follows the reabsorbed sodium leading to increased blood pressure.

In Conn syndrome, the overproduction of aldosterone by an adenoma causes excessive water retention, leading to hypertension, and potassium and hydrogen ion wasting in the urine, leading to hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis.

Secondary

Secondary hyperaldosteronism is due to over activity of the renin-angiotensin system.

High serum renin levels and high aldosterone levels (directly stimulated by the renin)

Low intravascular volume stimulates renin-angiotensin system which increases aldosterone production

Causes include:

Congestive heart failure

Cirrhosis

Chronic renal failure

Nephrotic syndrome

Renal artery stenosis

Diagnosis: Increased aldosterone levels with high plasma renin. Renin levels differentiate primary from secondary hyperaldosteronism

Treatment: Correct inciting causes, beta-blocker or diuretic for hypertension

Symptoms

Clinical Presentation:

Elevated aldosterone levels → hypertension (due to Na/H2O retention)

Elevated aldosterone → ↑ K+ and H+ wasting in the cortical collecting ducts → metabolic alkalosis and hypokalemia

Hypokalemia → metabolic alkalosis due to increased transcellular exchange of K+/H+

Alkalosis causes the COOH side groups of serum albumin → COO- → causes increased binding of Ca2+ → decreased free Ca2+ concentration

Hypokalemia can also lead to symptoms of muscle weakness as well as cardiac changes visible on EKG (classically described as U-waves)

Diagnosis

Plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC), plasma renin activity (PRA), and the PAC:PRA ratio are the initial approach to diagnose primary hyperaldosteronism, followed by an adrenal CT.

Increased PAC (≥ 15) and decreased PRA, with PAC:PRA ratio ≥ 20, are characteristic of primary hyperaldosteronism. This is not a confirmatory test and requires follow up with aldosterone suppression testing.

Aldosterone suppression testing is used to confirm a diagnose of hyperaldosteronism in a patient with elevated PAC/PRA ratio. It is performed with orally administered sodium chloride and measurement of urinary aldosterone.

Once the diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism is confirmed, adrenal CT is used to distinguish between Conn syndrome (adrenal adenoma) and idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (often bilateral adrenal hyperplasia).

Treatment

Treatment consists of controlling hypertension and hypokalemia with an aldosterone-receptor antagonist, and surgically removing the affected adrenal gland.

Aldosterone-receptor antagonists such as high-dose spironolactone or eplerenone normalize potassium and reduce blood pressure. Potassium supplements may also be used.

The preferred treatment for patients with primary aldosteronism due to unilateral aldosterone hypersecretion (e.g. adrenal adenoma) is unilateral adrenalectomy.

Following surgery:

Spironolactone and any potassium supplements should be discontinued.

Antihypertensive therapy should be decreased if possible.

Plasma aldosterone should be measured the day after surgery.

Potassium levels should be monitored during hospitalization and then weekly for the next four weeks to check for hyperkalemia.

Sodium-rich diet is recommended following discharge.

Complications of primary hyperaldosteronism include metabolic alkalosis, mild hypernatremia, and increased GFR with urinary albumin excretion. Primary hyperaldosteronism is also associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcemia in outpatients.

The etiologies of primary hyperparathyroidism include:

Benign adenoma of a parathyroid gland (85%)

Parathyroid hyperplasia (15%)

Parathyroid carcinoma (1%)

Mutations in the tumor suppressor MEN1 (MEN 1 syndrome) and the oncogene RET (MEN 2A syndrome) are associated with the development of primary hyperparathyroidism due to parathyroid adenoma or hyperplasia.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs when parathyroid glands are chronically stimulated to release PTH due to hypocalcemia and/or hyperphosphatemia due to another cause(e.g. chronic renal disease).

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is most commonly caused by chronic renal failure. Less commonly, it can be caused by vitamin D deficiency (e.g. chronic pancreatitis, small bowel disease).

Tertiary hyperparathyroidism refers to a state of abnormally elevated, autonomous PTH secretion and hypercalcemia due to end stage renal disease. It is often seen in patients following a renal transplant.

The hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and low vitamin D seen in patients with chronic renal disease induces persistent stimulation of the parathyroid gland, subsequent parathyroid hyperplasia, and can ultimately lead to tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

(Recall that hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and low calcitriol are all physiological stimuli for PTH secretion).

Symptoms

Primary hyperparathyroidism most commonly presents as asymptomatic hypercalcemia that is discovered incidentally on laboratory analyses.

Signs/Symptoms of hypercalcemia (mnemonic: “Bones, stones, groans and moans”):

Bones → Osteitis fibrosa cystica (from bone resorption), osteoporosis, musculoskeletal: weakness, bone pain and pathologic fractures.

Stones → Renal: 20% have calcium nephrolithiasis. Flank pain and/or hematuria may be present in the presence of kidney stones

Groans → Gastrointestinal: abdominal pain, nausea, constipation, PUD, pancreatitis

Moans → Mental: confusion, coma, seizures, psychiatric disturbances (depression). This is seen at very high levels of hypercalcemia.

Cardiac: heart failure and arrhythmias

Other symptoms of hypercalcemia can include, polyuria (due to diabetes insipidus) and hypertension (due to vasoconstriction of the blood vessels).

Diagnosis

After the incidental finding of hypercalcemia, the next steps in the workup of a patient with suspected primary hyperparathyroidism are to repeat the serum calcium measurement and order a parathyroid hormone (PTH) level.

Laboratory findings that are suggestive of primary hyperparathyroidism include:

Hypercalcaemia with hypercalciuria

Elevated or normal PTH in the setting of hypercalcemia

(PTH should be low in hypercalcemia due to negative feedback)

Hypophosphatemia

Primary hyperparathyroidism can be distinguished from secondary hyperparathyroidism by the serum calcium level:

Primary hyperparathyroidism: hypercalcemia

Secondary hyperparathyroidism: hypocalcemia

The finding of multifocal subperiosteal bone resorption on radiographs is pathognomonic for primary hyperparathyroidism. It often involves the tufts of the distal phalanges.

Treatment

One of the main treatments for primary hyperparathyroidism is actually surgical removal of the parathyroid adenoma. Indications for surgery include:

The presence of an elevated creatinine level

Hypercalcemia

Presence of kidney stones

Osteoporosis

The medical management of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism includes:

Bisphosphonates (e.g. alendronate)

Cinacalcet: Increases the sensitivity of the calcium-sensing receptor in the parathyroid gland to circulating calcium, which decreases the secretion of parathyroid hormone.

The medical management of patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism and chronic kidney disease includes:

Restricting dietary phosphate intake

Calcium-based phosphate binders

Vitamin D

The mainstay of treatment for patients with tertiary hyperparathyroidism is parathyroidectomy.

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is caused by an excess of thyroid hormone, which is responsible for controlling cellular metabolism and energy consumption, resulting in a hypermetabolic state.

Thyroid hormone is secreted by the thyroid gland and has two circulating forms, T3 and T4. The vast majority of hormone is produced as T4, then converted to the more active T3 in the periphery.

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), secreted by the anterior pituitary, acts on the thyroid gland to stimulate thyroid hormone secretion.

Free T3 and T4 exert negative feedback on the anterior pituitary, suppressing TSH secretion.

Thyroid hormone is bound by thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) in the plasma, which can reduce the amount of free thyroid hormone, and thus its pharmacological effects.

Conditions where TBG is increased (e.g. pregnancy) or decreased (e.g. liver failure) can affect total T3 or T4 levels. Increased estrogen during pregnancy causes increased TBG, which results in increased total T3 and T4 levels. However, the free T3 and free T4 levels are actually normal (therefore, pregnancy is not a hyperthyroid state).

Symptoms

Hyperthyroidism presents with constitutional and systemic symptoms related to the hypermetabolic state.

The hypermetabolic state results in increased heat production with heat intolerance and excessive sweating.

The hypermetabolic state also results in weight loss despite an increased appetite.

Neurological symptoms include insomnia, tremulousness, hyperreflexia, and irritability or anxiety.

Gastrointestinal symptoms include diarrhea.

Cardiac symptoms include tachyarrythmias.

Diagnosis

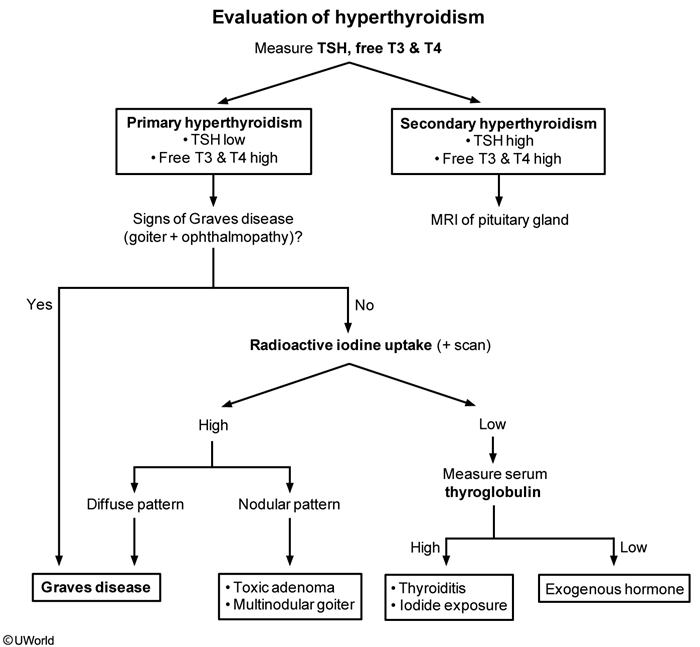

Serum TSH is the best initial test for the workup of hyperthyroidism.

TSH is decreased in primary hyperthyroidism – a TSH level within the normal range excludes clinical hyperthyroidism.

If TSH is below the normal range, a free serum T4 concentration should be obtained.

A decreased TSH and a normal T4 may indicate isolated T3 elevation as a cause of hyperthyroidism, and an indication for measurement of plasma T3.

Radioactive iodine (using iodine 123) scans can establish the relative iodine uptake of different parts of the thyroid, and is useful in determining the metabolic activity of the thyroid, and the presence of adenomas or goiters.

In Graves disease 123I uptake is diffusely increased throughout the whole thyroid gland.

In patients with a toxic multinodular goiter, uneven 123I uptake is seen, with occasional autonomous “hot” nodules demonstrating increased 123I uptake.

If the hyperthyroidism is due to exogenous thyroid hormone intake, a decreased 123I uptake will be observed.

In iatrogenic hyperthyroidism, patients with hypothyroidism may take too much of their prescribed thyroid hormone replacement medication.

In surreptitious hyperthyroidism, patients take thyroid hormone for secondary gain.

In both cases, excess thyroid hormone negatively feeds back on the pituitary, leading to decreased TSH. This decrease in thyroid activity manifests as decreased 123I uptake, with thyroid gland atrophy.

Graves

Grave's disease is hyperthyroidism resulting from thyroid-stimulating autoantibodies.

Females are affected more often than males, and peak age of onset is between 20 to 40.

Grave's disease is caused by a decrease in self-tolerance to thyroid auto-antigens and production of:

TSI (thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin), an IgG that binds and activates TSH receptor. TSI mimics the action of TSH via type II hypersensitivity. TSI is relatively specific for Graves disease.

Anti-Tg (thyroglobulin) and anti-TPO (thyroid peroxidase) antibodies, which are often present.

The triad of histological findings:

Diffuse hypertrophy and hyperplasia of thyroid follicular epithelial cells→ abundant tall columnar cells lining the follicles

Colloid appears pale with scalloped (moth-eaten) margins due to ↑ absorption

Lymphocytic infiltrate → germinal centers are common (germinal centers should NOT be in the thyroid; they are normal in lymph nodes)

Symptoms

Three physical examination findings classically associated with Graves disease are:

Proptosis (exophthalmos)

Pretibial myxedema

Thyroid bruit

Symptoms may include heat intolerance, weight loss, weakness, palpitations, frequent defecation, increased appetite, oligomenorrhea, or anxiety.

Graves’ exophthalmos is due to the accumulation of glycosaminoglycans and adipose in retro-orbital tissue, and occurs in 50% of patients. Patients may also complain of weakness of extraocular movements.

Pretibial myxedema is a scaly thickening and induration of the skin overlying the shins with nonpitting edema that occurs in 1-2% of patients with Grave's disease.

Diagnosis

In Grave's disease, TSH is low and T4 is elevated.

Antibodies to the TSH receptor are usually present. Other autoantibodies, such as those seen in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis can be seen with Grave's disease. These include anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies.

Treatment

β-blockers (e.g. propranolol) are indicated to control the symptoms of increased sympathetic nervous system tone (e.g. anxiety, tachycardia, sweating). Furthermore, propranolol decreases peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 by interfering with the activity of 5'-deiodinase, producing a net decrease in thyroid hormone actions at target tissues.

Thioamides [e.g. propylthiouracil (PTU) and methimazole] may induce remission by blocking new thyroid hormone production via inhibition of the organification and coupling steps of thyroid hormone synthesis. In addition, PTU (but not methimazole) also inhibits peripheral conversion of T4 to T3.

Propylthiouracil is the preferred treatment of hyperthyroidism in the first trimester since methimazole is teratogenic. Methimazole switched after first trimester to decrease risk of PTU induced liver injury. Pregnancy is a contraindication to radioactive iodine ablation of the thyroid, due to the risks to the fetus.

The definitive treatment of Graves disease is radioactive iodine ablation of the thyroid. However, titers of antibody increase significantly following RAI therapy, and RAI can cause worsening of ophthalmopathy. For this reason, administration of glucocorticoids with RAI is often advised to prevent complications in patients with mild ophthalmopathy.

Surgery (e.g. subtotal or total thyroidectomy) is used to treat hyperthyroidism under certain conditions, which include:

Very large goiters (≥80 g)

Goiters causing dysphagia or upper airway obstruction

When radioiodine are contraindicated

Graves' ophthalmopathy (which radioiodine can exacerbate)

Pregnant and allergic to antithyroid drugs

Young patients with toxic adenoma or toxic multinodular goiter (MNG)

The most severe direct complication of hyperthyroidism is thyroid storm.

Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia is defined as a blood glucose level of less than 65 mg/dL.

Normal blood glucose is 65-100 mg/dL.

Hypoglycemia in a diabetic patient is common, and may be due to a number of causes:

Taking too much insulin relative to food intake

Exercising more than normal without sufficient food intake

Taking certain medications, such as sulfonylureas, especially in kidney failure

Incomplete gastric emptying in a diabetic patient with gastroparesis can cause fluctuations of blood glucose.

Causes of fasting hypoglycemia include:

Liver disease, due to reduced hepatic gluconeogenesis

Adrenal insufficiency

Alcoholism

Insulinomas

Diabetes mellitus

Post-prandial hypoglycemia, or hypoglycemia that occurs after meals, often has an uncertain etiology, but may be seen in:

Hypothyroidism

Post-bariatric surgery

Whipple's triad, commonly thought of as a clinical test for an insulinoma, can also be used as a confirmatory clinical test for hypoglycemia. The triad includes:

Symptoms of hypoglycemia, such as:

Autonomic: tremors, tachycardia, or diaphoresis

Neurologic: confusion, lethargy, behavior or personality changes, seizure, syncope

Low blood glucose levels associated with these neurologic and autonomic symptoms. Note that with an insulinoma, blood glucose levels are <50 mg/dL.

Symptom resolution with normalization of blood glucose levels

Diagnosis

The diagnostic workup for hypoglycemia is often broad due to large differential diagnosis. The most important parts of the workup are the patient's history, blood glucose level, insulin panel, and assessment of organ function.

Assess organ function:

Liver disease using AST and ALT

Hypothyroidism using TSH

Adrenal insufficiency using morning cortisol

Factitious hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar due to surreptitious injection of insulin in a non-diabetic person, may be suspected in someone who has access to injectable insulin (such as a family member of a diabetic, or a health care worker).

To differentiate factitious hypoglycemia from other causes, obtain labs while the patient is hypoglycemic:

Serum insulin

Blood glucose

Proinsulin

C-peptide

Elevated insulin with reduced C peptide indicates excessive use of exogenous insulin, either in a diabetic patient who overdosed or in a non-diabetic patient using insulin surreptitiously (factitious hypoglycemia).

C-peptide level, proinsulin, and insulin levels are elevated when pancreatic secretion of insulin is increased (insulinomas, use of sulfonylureas).

In patients with unequivocal or elevated plasma insulin, C-peptide, and proinsulin values, the presence of insulin or insulin receptor antibodies can distinguish between insulin autoimmune hypoglycemia and insulinoma.

Treatment

Treatment of hypoglycemia is twofold, involving:

Acute treatment of the hypoglycemic episode

Long-term treatment of the underlying cause, with the goal of preventing future hypoglycemic episodes.

The acute treatment of hypoglycemia in patients with impaired consciousness depends on whether IV access has been established:

No IV access: glucagon (subcutaneous or intramuscular)

Established IV access: dextrose (intravenous, 25 g of 50% glucose)

Prevention of hypoglycemia is particularly important in those prone to low blood sugar, such as brittle diabetics. For prevention of fasting hypoglycemic episodes:

Keep sugar tablets (e.g. a Pez dispenser) available at all times.

Keep a glucagon emergency kit available.

For prevention of post-prandial hypoglycemic episodes:

Encourage the patient to eat frequent small meals throughout the day

Perform a thorough medication review to rule out medication-induced hypoglycemia

Insulinoma

An insulinoma is a neuroendocrine, insulin secreting pancreatic tumor, which results in wide fluctuations in blood sugar.

Patients typically present with fasting hypoglycemia and neuroglycopenic symptoms such as diplopia, dizziness, diaphoresis, and tachycardia.

Insulinomas are so rare that few institutions have gathered enough information to provide good demographic data. Insulinomas do have a high association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN type 1).

The diagnosis of insulinoma is made based on:

Clinical symptoms of hypoglycemia

Biochemical testing

Suppression testing

Suppression testing is based on the principle that insulin levels should decrease after prolonged fasting, since hypoglycemia suppresses insulin secretion.

The patient is admitted to the hospital for surveillance during a 72-hour fast.

During this time, blood glucose is monitored frequently.

When blood glucose levels are < 50 mg/dL, or when the patient experiences hypoglycemic symptoms, blood is drawn for serum glucose, insulin, proinsulin, and C-peptide levels. The patient is then given IV dextrose or calorie-containing food or drink to reverse the hypoglycemia.

Non-suppression of serum insulin levels in the setting of hypoglycemia is strongly indicative of an insulin-secreting tumor.

Because insulinomas can be very small, a radiographic workup is only done after the diagnosis is confirmed with the Whipple’s triad, biochemical testing, and suppression testing (discussed above).

After confirmation, CT scan of the abdomen with contrast and endoscopic ultrasound are used to localize the pancreatic lesion.

Definitive treatment of insulinoma is surgical removal of the tumor.

Depending on the location of the lesion, options for surgery may include a distal pancreatectomy or a partial pancreatectomy. A very small percentage of insulinomas are metastatic at the time of diagnosis. These tumors may metastasize to the local lymph nodes or to the liver.

Patients who fail surgical treatment or cannot undergo surgery (due to metastasis) should receive medical therapy such as diazoxide, which inhibits insulin release.

Thyroid Cancer

There are four major types of thyroid cancer:

Papillary

Follicular

Medullary

Anaplastic

The clinical presentation can vary, but is generally highlighted by painless enlargement of the thyroid gland.

Labs may show normal or decreased levels of thyroid hormones

Diagnostic workup includes ultrasound, FNA (fine needle aspiration) and radionucleotide scans (scintigrams).

First step is to get an ultrasound which, if necessary, is followed by a guided FNA.

If suspicious, one can order a radionucleotide scan.

Thyroid carcinomas generally present as cold nodules on scintigrams.

Biopsy provides the definitive diagnosis.

More advanced lesions may present with signs of local invasion including hoarseness (from recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement), dysphagia and cough. CT scans of the chest may need to be done as well as bone scans to look for metastasis.

Factors that should raise your suspicion for malignancy:

Solid nodule palpated or seen on US

Age (20-60) and increases with age

Male

Cold nodule on scintigram

History of neck irradiation

Papillary Carcinoma: > 85% of thyroid cancer cases

Common in younger patients, especially those who have been exposed to ionizing radiation.

Propensity for lymphatic spread, thus can present with lymphadenopathy.

Histologically, cells are described as having “Orphan Annie eye nuclei” because of the characteristic shape they assume.

Another common histological finding is psammoma bodies.

*Excellent prognosis.

Follicular Carcinoma: 5-15% of thyroid cancers.

More common in females, and patients age 40-60.

Propensity for hematogenous spread, thus can present with distant mets (liver, bone, lungs)

Generally good prognosis

Medullary Carcinoma: 5% of thyroid cancer cases

Classically associated with MEN 2A and MEN 2B syndromes due to inherited mutation of RET proto-oncogene, although 70% of cases are caused by sporadic mutation.

Parafollicular (C-cells) are malignant → ↑ calcitonin production.

Cells stain positive for amyloid

Anaplastic Carcinoma: < 5% of thyroid cancer cases:

Worst prognosis

Extremely aggressive

Poorly differentiated

Most common in patients age > 65

The general treatment of thyroid cancer and benign solid nodules involves:

Surgical removal plus radioactive iodine ablation

Lobectomy if nodule <1cm

Total thyroidectomy if >1cm

Post-surgery, the patient is started on levothyroxine. This is to inhibit additional thyroid hormone production (in lobectomy) and reduce recurrence or conversion to malignancy. In total thyroidectomy, it is used to replace thyroid-hormone since the gland is no longer present to do so.

Adrenal Mass

This patient was incidentally found to have an adrenal mass. Guidelines for surgical resection include:

tumors > 6 cm

features on CT suspicious for malignancy (high attenuation, irregular borders, inhomogeneous)

and those that are hormonally active.

The first step in the evaluation of an incidentally discovered adrenal mass is to perform a biochemical workup to determine if the tumor is functional or nonfunctional (E). In practice, it is common to order a single battery of tests: serum aldosterone, plasma renin activity, and a 24-h urine collection to simultaneously measure catecholamines, metanephrines, and cortisol. Given that this patient is normotensive, the suspicion for pheochromocytoma and hyperaldosteronism is low. In addition, adrenal masses < 6 cm are unlikely to be malignant. If the mass is found to be a hormonally active adrenal adenoma, then laparoscopic adrenalectomy (D) would be recommended. If biochemical testing reveals a nonfunctioning mass, this small lesion may be observed with interval CT scanning (A). Percutaneous needle biopsy (B) cannot readily distinguish between benign and malignant primary adrenal tumors.

Open adrenalectomy is preferred when malignancy is suspected, as this allows for a wider resection with en bloc resection if adjacent structures are involved and eliminates the possibility of seeding the port sites that may occur with laparoscopic adrenalectomy (C). Laparoscopic adrenalectomy is preferred for benign lesions. Radiation therapy (D) is not the mainstay of treatment for adrenal cortical carcinoma. Percutaneous biopsy (E) is not recommended as there are no histologic features that diagnose adrenal cortical carcinoma and a biopsy may risk seeding the biopsy tract.

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst

Ectopic thyroid gland may be associated with thyroglossal duct cysts so it’s necessary to confirm the thyroid gland is in its correct anatomic location prior to surgical intervention. The definitive management involves thyroglossal duct cyst excision or the Sistrunk procedure. Reassurance and observation (C) are inappropriate as thyroglossal duct cysts have a high rate of recurrent infections and a small risk of progressing to malignancy.

Thyroidectomy complications

Don’t forget the ABCs. This patient has a compromised airway and is in moderate respiratory distress. Normally, the fi rst step to ensure an airway is via endotracheal intubation (B). However, a neck hematoma is in a closed space that leads to compression of the airway that may render safe intubation difficult or impossible. As such, the first step is to immediately open the neck wound at the bedside to decompress the hematoma. This will typically relieve the airway obstruction. The patient can then be transported emergently to the operating room for intubation, wound exploration, adequate hemostasis, and subsequent wound closure (C). Although thyroidectomy is considered a safe procedure, one well-known complication is airway obstruction following bleeding and hematoma formation which occurs within the fi rst 24 h after thyroidectomy.

The superior laryngeal nerve lies adjacent to the superior thyroid artery and is thus at high risk of being injured during mobilization of the thyroid, particularly the superior pole. The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve permits singing in a high pitch. This nerve may be injured in up to 25 % of cases but is usually asymptomatic unless the patient is a singer or voice professional.

Damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve on one side results in a paralyzed vocal cord in a median or paramedian position. This manifests as hoarseness (A) and sometimes aspiration. The rate of permanent unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury during thyroidectomy should be less than 2 % in expert hands. If both recurrent laryngeal nerves were injured during a total thyroidectomy, then both vocal cords could be paralyzed, and this may lead to a compromised airway which may necessitate a permanent tracheostomy (E). A droop in the corner of the mouth results from injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. Swallowing is controlled by multiple nerves (C) including the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and/ or hypoglossal nerves.

Parathyroidectomy

The surgical treatment of hyperparathyroidism depends on whether the pathology is a single adenoma (most common, remove single gland), more than one adenoma (remove abnormal ones), or four gland hyperplasia (remove 3.5 glands ). Distinguishing these entities is not always obvious. Because of the short half-life of PTH (about 4 min), intraoperative rapid PTH testing aids in determining the completeness of parathyroid resection. The most commonly used protocol involves drawing PTH levels at the time of gland excision and again 10 min post-excision. A fall of >50 % in the PTH level is associated with a 98 % long-term cure rate. Given the small size of the parathyroid glands, it is generally not recommended to biopsy all of them for frozen section (B), as such a biopsy may render all the glands ischemic. Transient hypocalcemia is expected following parathyroidectomy so postoperative serum calcium level (D) is not indicative of cure. Oral calcium supplementation can help alleviate minor symptoms. Intraoperative ultrasound (A) is sometimes used when the abnormally enlarged gland cannot be found. Sestamibi (E) may be used if recurrent or persistent hyperparathyroidism develops, but is not routinely used for confi rmation of successful surgery.

Sestamibi scanning involves using a radioisotope, technetium-99 m, which is taken up by cells with high mitochondrial activity. It is more accurate for single adenomas than for four gland hyperplasia. Sestamibi scanning and to a lesser extent ultrasound (B) are the most frequently used imaging tests to localize the involved gland(s) in primary hyperparathyroidism.

Last updated