01 Cardiology

General

Cardiac Anatomy

The coronary arteries originate from the aortic sinus, the region of the aorta just above the aortic valve.

The right coronary artery (RCA) supplies the right ventricle, as well as theposterior portion of the interventricular septum in most people. When the RCA supplies the posterior heart, this is known as right dominance.

The right coronary artery (RCA) passes anteriorly, to the right of pulmonary artery root, coursing posteriorly through the sulcus between the right atrium and right ventricle.

The sinoatrial artery originates from the right coronary artery (RCA) to supply the sinoatrial node. Acute thrombus in the proximal RCA may result in the failure to generate regular sinus rhythm.

The right marginal artery originates from the right coronary artery (RCA), and serves as the main supply to the right ventricle.

In most people, the right coronary artery(RCA) also gives rise to the posterior descending artery (PDA), which courses between the two ventricles posteriorly and supplies the posterior region of the interventricular septum, as well as some of the posterior right and left ventricles. When the RCA gives rise to the PDA (as it does in 80% of people), this is known as right dominance.

The two main branches of the left coronary artery (LCA, sometimes 'LMCA' for left main coronary artery) are the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and the left circumflex artery (LCx).

The left coronary artery (LCA) passes anteriorly, to the left of the pulmonary artery root, then divides into its two major branches about halfway around the left atrium. Because the course of the LCA is so short, it is typically not considered to have its own proper supply domains.

The left anterior descending artery (LAD) descends between the right and left ventricle to supply the anterior interventricular septum, the more left aspects of the right ventricle, and the majority of the left ventricle.

The left circumflex artery (LCx) courses posteriorly between the left atrium and left ventricle to supply the more posterior aspects of the left ventricle.

In some people (20%), the left circumflex artery (LCx) gives rise to the posterior descending artery (PDA), which supplies theposterior region of the interventricular septum as well as some of the posterior right and left ventricles. This is known as left dominance.

Bloodflow through the coronary arteries is biphasic, with greater flow occurring during diastole.

The systolic ventricular pressure is far greater on the left than on the right, such that the left ventricle is essentially perfused during diastole only.

Cardiac Physiology

Cardiac output (CO) is defined as the _product_of the stroke volume (SV) and the heart rate (HR): CO = SV x HR

Stroke volume is the amount of blood ejected from a ventricle during systole. With respect to the left ventricle, this is equal to the difference between left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV): SV=LVEDV−LVESVSV = LVEDV - LVESVSV=LVEDV−LVESV.

A decrease in stroke volume should produce a compensatory increase in heart rate in an effort to maintain cardiac output, as occurs in the settings of hypovolemic shockand (sometimes) distributive shock.

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) is defined as the average arterial pressure over the cardiac cycle, and is derived from central venous pressure (CVP), cardiac output (CO), and systemic vascular resistance (SVR): MAP=(CO×SVR)+CVPMAP = (CO\times SVR)+CVPMAP=(CO×SVR)+CVP

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) for a normal person at rest can be estimated from the systolic (BPS) and diastolic (BPD) blood pressures, taking into account the relative contributions of each phase of the cardiac cycle: MAP≈13BPS+23BPDMAP \thickapprox \frac{1}{3}BP_S + \frac{2}{3}BP_DMAP≈31BPS+32BPD. (MD calc provides an easy way to do this on the wards.)

Since MAP accounts for arterial pressure during systole and diastole, it is considered the most physiologic measurement of the pressure perfusing the body’s organs.

Arterioles are primarily responsible for determining systemic vascular resistance in the absence of anatomic anomalies (e.g. arteriovenous malformations).

An adequate systolic arterial blood pressure is required to perfuse the body’s organs; accordingly, a decrease in systemic vascular resistance should produce a compensatory increase in cardiac output. This is primarily due to an increase in heart rate, and is observed in the setting of septic shock, a form of distributive shock.

CAD

CAD Overview

Coronary artery disease occurs when the coronary arteries become progressively narrowed and lose their ability to dilate, causing a mismatch between myocardial oxygen supply and demand. This is most commonly the result of extensive atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Symptomatic CAD is divided into stable angina and the acute coronary syndromes, including unstable angina, NSTEMI and STEMI; however, many patients with CAD are asymptomatic.

Heart disease as a broad etiologic category remains the leading cause of death in the United States at 253 per 100,000 people. Ischemic heart disease is the single most common diagnosed cause of death in the US at 123 per 100,000 people.

Coronary artery disease is strongly associated with major modifiable risk factors:

Tobacco usage

Hypertension

Sedentary lifestyle

Obesity

Diabetes mellitus

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is associated with the following major uncontrollable risk factors:

Age > 65

Sex: men are at higher risk

Family history: premature coronary disease in men under 55 and women under 65

Coronary artery disease begins as intimal fatty streaks early in life, but the plaques and thrombi that result in the clinical consequences develop later on in adulthood.

For diagnosis and treatment of CAD-related risk factors, see:

Atherosclerosis

Hypercholesterolemia

Primary Hypertension

Secondary Hypertension

For diagnosis and treatment of CAD-related conditions, see:

CAD: Stress tests

CAD: Stable angina pectoris

Acute Coronary Syndromes

CAD Diagnosis

The resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is generally the initial diagnostic test used to evaluate ischemic heart disease, because it allows for the most physiologic evaluation of myocardial perfusion.

Most patients require stress testing for further diagnosis. The initial stress test could be any one of the following and should be based on resting ECG, patients ability to perform exercise, and available technology:

Exercise ECG with/without imaging

Pharmacologic ECG with imaging

Patients who cannot exercise can undergo pharmacologic stress testing, in which a drug replaces exercise as the stimulus for increasing myocardial perfusion. In pharmacologic stress testing, ECG is always combined with an imaging modality.

Dobutamine, a cardiac inotrope, is used in pharmacologic stress echocardiography to evaluate patients who cannot exercise.

The vasodilators adenosine and dipyridamole are used in radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging (rMPI). Perfusion is restricted in territories supplied by stenotic vessels which are unable to dilate, so there is comparatively less radionuclide uptake in these regions.

The type of diagnostic testing that is appropriate for a given patient is dependent upon his or her pre-test probability of CAD . Determining the appropriate test for a given patient vignette is very high-yield for the USMLE Step 2.

The pre-test probability of coronary artery disease is described in the attached chart. As a reminder, the pre-test probability affects the false negative and false positive rates. Low probability patients are more likely to have a falsely positive test, while high probability patients are more likely to have a false negative. This is why patients with low pre-test probability for CAD are not screened.

Typical: substernal pain, increased with exersion, relieved by rest/nitrate

Atypical: 2 of 3

Nonanginal: 0 or 1

In general, diagnostic testing for CAD is warranted in patients with symptoms of CAD, asymptomatic patients with high pre-test CAD probability, or patients with newly diagnosed heart failure.

Asymptomatic

The only asymptomatic patients who should undergo stress testing are those with a global risk of >20% for clinical CAD within the next 10 years. They should undergo exercise ECG unless contraindicated due to inability to exercise. (There are several models discussed in the 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for determining 10-year global risk for CAD, and this is generally beyond the scope of the USMLE exams--and thus of this product. One popular model is the Framingham risk score, which takes into account factors such as age, sex, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, smoking, systolic blood pressure, and treatment with antihypertensive medications. Other models factor in diabetes and family history.)

Symptomatic

Symptomatic patients with low or intermediate pre-test probability who are both 1) able to exercise and 2) have an interpretable ECG should undergo exercise stress testing.

Stress radionuclide imaging or echo are the tests-of-choice for most symptomatic patients who are unable to exercise or have an uninterpretable ECG. They may also be used for symptomatic intermediate and high pre-test probability patients.

Stress cardiac MRI is primarily for symptomatic high pre-test probability patients.

In other words, a symptomatic patient with high pre-test probability should receive stress radionuclide imaging, stress echo, stress MRI, or coronary angiography, NOT an exercise ECG.

CHF

Newly diagnosed CHF should be evaluated for coronary artery disease similarly to symptomatic patients with high pre-test probability: stress radionuclide imaging, stress echo, stress MRI, or coronary angiography, NOT an exercise ECG.

Exercise stress testing combines controlled exercise (e.g. treadmill) with an EKG to visualize ischemic changes or induce angina.

Exercise stress ECG is considered positive for ischemic coronary artery disease with any of the following results:

Greater or equal to 1 mm ST-segment depression which is horizontal or down-sloping

Greater than 10 mm Hg drop in systolic blood pressure (SBP) from resting value, OR failure to elevate SBP to > 120 mm Hg

Some drugs should be held for exercise stress tests because they will, by their nature, alter the EKG results:

Beta-blockers

Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (i.e. diltiazem, verapamil)

Certain antiarrhythmic agents (e.g. amiodarone, sotalol)

Digoxin

Nitrates

Exercise stress testing is contraindicated in unstable patients (e.g. hypertensive emergency, aortic dissection, acute myocardial infarction), in patients who cannot exercise (e.g. mobility restrictions) or patients with uninterpretable EKGs (e.g. patients with pacemakers, resting ST-segment changes, bundle branch blocks, or on digoxin.)

Low-grade coronary artery stenosis (less than 50%) isn’t severe enough to cause EKG changes, which means the exercise stress test will appear normal.

Nuclear stress testing uses a radioactive substance like thallium-201 or technetium-99m (Tc-99m) sestamibi to allow visualization of heart tissue perfusion by single photon emission CT scan during rest and exercise.

Thallium accumulates in well-perfused heart tissue during a nuclear stress test.

Nuclear stress tests are appropriate in patients with baseline EKG abnormalities (e.g. bundle branch block, left ventricular hypertrophy, or a pacemaker) because the results are not affected by these abnormalities.

Stress echocardiogram combines an exercise stress test with an echocardiogram, which enables recognition of heart wall motion abnormalities during exercise.

Coronary angiography is the most sensitive and specific for CAD, however, it is the most invasive. Unlike all other diagnostic tests, it allows for immediate intervention (e.g. stent placement).

See Acute Coronary Syndromes for more information.

STEMI Diagnosis

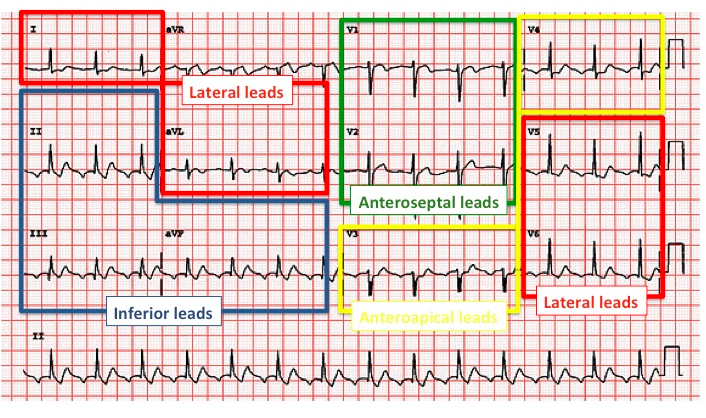

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a type of acute coronary syndrome in which a patient presents with new (or presumed new) territorial ST-segment elevation on electrocardiogram (ECG).

Specific ECG diagnostic criteria for STEMI are:

> 1mm persistent ST-elevation in 2 or more contiguous leads, or

> 2mm persistent ST-elevation in leads V2 and V3, or

New left bundle-branch block (LBBB), or

True posterior MI (look for reciprocal ST depression in the anterior leads)

The EKG in a STEMI changes over time. It is important to recognize that these changes do not always occur in this classic sequence, and multiple findings may be simultaneously present.

Tall and peaked hyperacute T waves will be seen over the ischemic zone due to local hyperkalemia.

J point elevation with preservation of ST segment morphology

The ST segment develops convexity and becomes rounded upward, merging progressively with the T wave

Pathologic Q waves develop as myocardium dies.

In patients who do not achieve reperfusion, persistent T wave inversions develop in the region of the infarct, but the ST segment returns to baseline

Territorial ST-segment elevation typically reflects transmural ischemia.

ST elevation in leads II, III, and aVF indicates an inferior infarct of the posterior descending artery or marginal branch.

ST elevation in leads I, aVL, and V5-V6 indicates a lateral infarct of the left anterior descending artery or circumflex.

ST elevation in leads V1-V2 indicates a septal infarct of the left anterior descending artery.

ST elevation in leads V3-V4 indicates anterior infarct of the left anterior descending artery.

Patients with inferior infarct should also be evaluated with a right-sided EKG for right-heart infarction. This is imperative because patients with right-sided infarction are preload dependent and cannot receive nitrates.

Serum cardiac enzymes, specifically cardiac-specific troponin T (cTnT), cardiac-specific troponin I (cTnI), and creatine kinase MB-isoenzyme (CKMB), are crucial for diagnosing and monitoring progression of a STEMI.

Troponins are more sensitive and specific for myocardial injury than creatine kinase (including the MB fraction.)

CKMB rises within 8 hours of infarction and returns to normal by 72 hours, but troponins remain elevated for 7-10 days after infarction and cannot be used to assess for reinfarction during this period.

In ruling out myocardial infarction, patients are typically admitted to have 3 separate sets of cardiac enzymes drawn, each 6-8 hours apart, as the overwhelming majority of patients with myocardial infarction will have positive enzymes by 16 hours.

STEMI Evaluation

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) occurs when a thrombus abruptly occludes an atherosclerotic coronary artery, leading to transmural ischemia with irreversible myocardial injury.

Slowly developing coronary stenosis typically does not cause STEMI because a rich collateral circulation develops; however, this does predispose a patient to unstable angina and NSTEMI.

The most important risk factors for STEMI are having multiple atherosclerotic risk factors (e.g. smoking, hyperlipidemia) and unstable angina.

Less common but still important risk factors for STEMI include hypercoagulability, cocaine use, and collagen vascular diseases.

Initial pharmacologic treatment of STEMI is the same as unstable angina/NSTEMI (mnemonic: BEMOANS):

β-blocker

Unless heart failure, bradycardia, heart block, cardiogenic shock

Enoxaparin (reduces probability of recurrent coronary events)

Morphine (if in severe pain)

Oxygen (if SaO2<90% or dyspnea)

Anti-platelet: aspirin plus P2Y12 inhibitor (e.g. clopidogrel)

Nitrates (primary benefit from preload reduction; also reduces afterload)

Statin (e.g. high-dose atorvastatin)

Glucocorticoids and NSAIDs (except aspirin) are contraindicated in STEMI because they impair healing of the infarcted region and increase the risk for ventricular wall rupture.

The definitive treatment for STEMI is reperfusion therapy, which should be considered for every STEMI patient.

Fibrinolysis with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), streptokinase, tenecteplase, or reteplase is referred to as “chemical reperfusion.”

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a form of mechanical reperfusion therapy which can be performed along with diagnostic cardiac catheterization. PCI with stenting was shown to offer a significant reduction in reinfarction or stroke at 30 days, as well as significant mortality benefit for high risk patients with TIMI score > 5. [Nielson et al. Circulation. 2010;121:1484.]

Chemical fibrinolysis is indicated for the treatment of STEMI in patients presenting within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms when PCI cannot be accomplished within 120 minutes of first medical contact.

Primary PCI without antecedent fibrinolysis is preferred in the following situations:

Patients with absolute or otherwise compelling contraindications to fibrinolysis

When the diagnosis is in doubt

When there is cardiogenic shock

Absolute contraindications to chemical fibrinolysis are blood, blood, blood, BP, brain:

Cerebrovascular hemorrhage at any time

Active internal bleeding

Suspicion of aortic dissection

Marked hypertension (systolic >180 or diastolic >110) at any time during the acute presentation

Nonhemorrhagic stroke or other cerebrovascular event within the past year

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is indicated as the primary reperfusion strategy for the treatment of STEMI in patients with occlusion of the left main coronary artery or patients with severe three-vessel involvement.

Stable Angina

Stable angina pectoris is a subtype of coronary artery disease in which chest pain due to myocardial ischemia occurs predictably during periods of increased oxygen demand (e.g., exercise) or decreased supply (e.g., hypotension) and is relieved by rest or nitroglycerin.

Typical angina is substernal chest pain most commonly described as a squeezing, tightness, pressure sensation that is provoked by exertion or emotional stress and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin. Its onset and offset are gradual and repeat episodes typically present the same way.

Note that chest pain relieved by nitroglycerin is NOT entirely specific for angina--nitroglycerin may also soothe the pain associated with diffuse esophageal spasm.

Atypical angina refers to chest pain symptoms that are typically non-cardiac in nature:

Sharp, knife-like, pleuritic chest pain

Primary location in the mid-to-lower abdomen

Discomfort is easily localized (e.g. patient points with one finger to where it hurts)

Pain is associated with or worsened by movement or palpation

Pain is either fleeting or persistent

Patients with stable angina present with complaints of chest pain lasting between 5 and 15 minutes which may radiate to the jaw, neck, or shoulders, and was brought on by physical exertion. Cardiac pain that occurs at rest is more consistent with unstable angina.

Profuse sweating, shortness of breath, and a feeling of impending doom are more suggestive of myocardial infarction and are not typically part of the presentation of stable angina pectoris.

Atypical symptoms like weakness, breathlessness, nausea, vomiting, and midepigastric discomfort or sharp chest pain are considered “angina equivalent” in the elderly and women. Diabetics may also have an atypical presentation due to decreased sensitivity of sensory neurons involved in the generation of typical angina.

The physical exam of a patient suffering from stable angina pectoris is normal.

During an attack, or more frequently during deliberately induced high-oxygen-demand states like stress tests, electrocardiogram (ECG) will generally reveal regional ST-segment depression.

Ischemia-induced myocardial dysfunction may result in a paradoxically split S2; an S3 and/or an S4 may be present as well, which is caused by delayed relaxation of the left ventricular myocardium and delayed aortic valve closure.

The gold standard for diagnosing stable angina pectoris is the exercise stress test.

Stable angina pectoris is primarily treated with lifestyle modification and medical managment, though some patients may require revascularization.

Lifestyle modifications alter the major modifiable risk factors for coronary artery disease:

Smoking cessation

Blood pressure control

Increased activity level

Weight loss

Diabetes control

Beta-blockers are recommended as first-line agents for the reduction of anginal episodes and to improve exercise tolerance. Fast-acting nitrates provide relief from acute anginal symptoms; long-acting nitrates or calcium channel blockers may be used in combination with a beta-blocker if angina persists. Calcium channel blockers are also appropriate for patients who cannot tolerate beta-blocker therapy.

Aspirin and statins help reduce risk of acute thrombus, and should be used in stable angina patients.

UA and NSTEMI

Unstable angina (UA) is defined as chest or arm pressure or pain with at least one of three features: (1) it occurs at rest (or with minimal exertion) for >10 minutes; (2) it is severe and of new onset; and/or (3) it occurs with a crescendo pattern (i.e. more severe, longer, or more frequent episodes.) Unstable angina may also be called “crescendo angina.”

The most common cause of UA/NSTEMI is believed to be rupture of coronary artery plaques and subsequent down-stream occlusion.

In unstable angina, complete obstruction is rare; incomplete stenosis or presence of well-perfused collaterals may prevent progression to complete infarction (e.g. ST-elevating myocardial infarction).

Unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) are, by definition, not associated with ST-elevation on EKG.

Some patients may present with ST-segment depression and/or T-wave inversion.

Territorial ST-segment depression typically represents a corresponding region of subendocardial (i.e. not transmural) ischemia. This occurs because the ischemic region is electrically depolarized even when the ventricle is at rest or repolarized, causing an elevation of the isoelectrical baseline. When the whole ventricle depolarizes, the ischemic region also depolarizes down to the same level. This gives the appearance that the ST segment is dropping below the isolectric baseline.

Unstable angina is not associated with changes in biomarkers for cardiac necrosis (troponins and CKMB).

NSTEMI is distinguished from unstable angina by the presence of elevations in cardiac enzymes. It is distinguished from STEMI by the absence of ST-segment elevation.

Patients who are elderly, have diabetes, or are women are more likely to present with atypical symptoms of ACS in the absence of chest pain, including:

Dyspnea

Weakness

Nausea, vomiting

Palpitations

All patients with suspected UA vs. NSTEMI should be admitted for telemetry and serial cardiac enzymes (i.e. at least two troponin measurements), as these are part of the TIMI score used to predict level of ACS risk and determine whether a patient may benefit from early coronary angiography and revascularization.

Immediate angiography and revascularization is recommended for patients with non-ST elevation ACS and at least one of the following:

Hemodynamic compromise or cardiogenic shock

Systolic heart failure

Recurrent or persistent angina despite medical therapy

Evolving mitral insufficiency or ventricular septal defect

Sustained ventricular arrhythmias

Initial pharmacologic treatment of UA/NSTEMI is the same as STEMI with the singular exception that fibrinolytics are never indicated. Otherwise, pharmacologic therapy includes (mnemonic: BEMOANS):

β-blocker

Unless heart failure, bradycardia, heart block, cardiogenic shock

Enoxaparin (reduces probability of recurrent coronary events)

Morphine (if in severe pain)

Oxygen (if SaO2<90% or dyspnea)

Anti-platelet: aspirin plus P2Y12 inhibitor (e.g. clopidogrel)

Nitrates (primary benefit from preload reduction; also reduces afterload)

Statin (e.g. high-dose atorvastatin)

The Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Risk Score allows for grading risk of serious adverse outcomes in UA/NSTEMI, which is slightly different than the TIMI risk score used for STEMI. If TIMI risk score ≥ 3, consider early low molecular weight heparin and angiography.

The components of the TIMI score for UA or NSTEMI are (1 point each) SCAARES:

Severe angina (≥2 events over the past 24 hours)

Coronary artery stenosis ≥50%

Age ≥65 years

Aspirin use within the past 7 days

Three or more Risk factors for CAD (Fam history, DM, HTN, Smoking, dyslipidemia)

Enzymes: elevated troponins or CKMB

ST segment changes on ECG

Prinzmetal Angina

Vasospastic angina (previously known as Prinzmetal or variant angina) is anginal chest pain caused by coronary vasospasm.

Cigarette smoking is the primary cardiovascular risk factor for vasospastic angina.

In contrast to angina pectoris, vasospastic angina is not associated with other cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and hypercholesterolemia.

Coronary artery spasm in vasospastic angina most commonly occurs at sites of atherosclerotic plaques, although it can also occur in normal vessels.

Vasospastic angina may be associated with other vasospastic conditions, particularly Raynaud phenomenon and migraine headache.

Vasospastic angina presents more commonly in younger patients without a cardiac history with seemingly random episodes of severe resting chest pain that occur most frequently at night.

During an episode of chest pain, patients will have ST segment elevation on electrocardiogram (ECG), followed by a return to a normal ECG as the vasospasm and chest pain relent.

ST-elevation is caused in this setting by transmural ischemia in the absence of collateral circulation.

There is a high prevalence of severe life-threatening arrhythmias (e.g. ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, or severe heart blocks) in variant angina, which is attributed to sudden coronary reperfusion.

Coronary angiography with a provocative test for vasospasm (e.g. ergonovine or acetylcholine infusion directly into the vessel) is the gold standard both for diagnosis and responsiveness to therapy.

Calcium-channel blockers (e.g. diltiazem) are the first-line treatment for vasospastic angina.

The pain of vasospastic angina is relieved by nitroglycerin.

Aspirin and nonselective beta blockers (e.g. propranolol) will worsen symptoms of vasospastic angina and should be avoided.

Since sumatriptan is associated with coronary vasospasm, it should be avoided in patients with vasospastic angina.

Recall that vasospastic angina is associated with other vasospastic disorders such as migraine headaches, so avoiding triptans in these patients is particularly relevant.

Post MI

The most common complication following myocardial infarction (MI) is arrhythmia.

Arrhythmias as a complication of MI typically occur during or immediately following the event.

Ventricular fibrillation is the most common cause of death in patients with or recently recovering from MI.

Infarction of parts of the interventricular septum may present with new onset atrioventricular or bundle branch blocks.

Structural complications of MI include ruptures and aneurysm.

The most common ruptures that occur as complications of myocardial infarction are:

Ventricular free wall rupture, resulting in acute pericardial tamponade

Ventricular septal rupture, resulting in a new ventricular septal defect murmur

Papillary muscle rupture, resulting in severe mitral regurgitation and hemodynamic collapse

**Note that the likelihood of any one of these occurring is predicted by the electrocardiogram at MI presentation.

Ruptures as a complication of MI generally occur 3 to 14 days following the event, once macrophages have cleared the debris.

Aneurysm

Aneurysms occur as a late (days to months) consequence of transmural infarcts that result in a large area of noncontractile transmural scar on a free wall which progressively dilates.

ECG findings suggestive of a left ventricular aneurysm include persistent ST elevation following a recent myocardial infarction and deep Q waves.

Sequelae of a left ventricular aneurysm include:

Cardiogenic shock

Arrhythmias

Thromboembolism (aneurysms are commonly filled with a clot)

The wall of a ventricular aneurysm paradoxically bulges outward during systole; this systolic bulge can be palpated on physical exam on the chest wall.

Pseudoaneurysm

Ventricular pseudoaneurysm is a complication of a MI that occurs when myocardial rupture is contained by pericardial or granulation tissue. In contrast to a true ventricular aneurysm, ventricular pseudoaneurysms are likely to rupture, leading to a potentially fatal hemorrhage.

Patients with left ventricular pseudoaneurysm are managed with emergency surgery since untreated pseudoaneurysms are prone to rupture.

Percarditis

The two inflammatory complications of MI include peri-infarction pericarditis (PIP) and Dressler's syndrome (postcardiac injury syndrome).

PIP is an acute inflammatory process extending to the pericardium that occurs 2 to 3 days following transmural MI as a normal response to clear necrotic tissue.

PIP presents with a pericardial friction rub with or without chest discomfort 2 to 3 days following MI.

The treatment of PIP is supportive, as most cases are self limited.

Dressler

Dressler's syndrome is an inflammatory response to previously sequestered pericardial antigens that develops 2-3 weeks following acute transmural MI.

Dressler's syndrome presents with low-grade fever, chest pain, pericarditis as evidenced by the presence of a friction rub on cardiac auscultation, and/or pericardial effusion. The time period will distinguish it from peri-infarction pericarditis (PIP).

Dressler’s syndrome is usually self-limited, but can be treated with aspirin or ibuprofen; prophylaxis may be provided with colchicine in the setting of cardiac surgery, but is not commonly used for MI patients.

MI long term management

Long-term management of patients who have suffered a myocardial infarction focuses on reducing risk of re-infarction and pathologic hypertrophy.

Important lifestyle modifications include smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary modifications targeted to decreasing weight, blood pressure, and cholesterol.

Important pharmacologic management BAA(N)S a second MI:

β-blocker

Low-dose Aspirin

ACE-inhibitor or ARB

Nitroglycerin (as-needed for recurrent angina)

Statin

**Note that nitroglycerin provides symptomatic relief only, while the other drugs reduce adverse remodeling and lower the risk for recurrent MI. These medications should be started before the patient leaves the hospital.

Patients who have received coronary interventions (e.g. PCI) should be loaded with aspirin and a platelet ADP receptor (P2Y12) blocker such as clopidogrel, ticagrelor, or prasugrel as soon as the diagnosis of STEMI is made, and should be discharged on a maintenance dose of these two antiplatelet medications.

The use of GpIIb/IIIa inhibitors is not routinely recommended for patients undergoing PCI for STEMI.

Chronic Heart Disease

Primary HTN

Primary (essential) hypertension is hypertension which occurs in the absence of an identifiable underlying etiology (i.e. idiopathic). It accounts for more than 95% of hypertension.

There are quite a few risk factors for the development of essential hypertension:

Alcohol consumption

Tobacco use

Depression

Excess dietary salt

Obesity

Geriatric population

Family history

Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

Blacks generally have a higher salt-sensitivity than whites, which contributes to a greater susceptibility to developing primary hypertension.

Primary hypertension is asymptomatic for many years. Headache may be the only symptom until complications develop.

Per 2017 AHA Hypertension Guidelines, primary hypertension is diagnosed if the blood pressure is determined on at least two separate occasions to be ≥130 mmHg systolic pressure and/or ≥80 mmHg diastolic pressure, and once common contributing factors have satisfactorily been ruled out.

At minimum, the following labs should be ordered in the workup of newly-diagnosed hypertension:

Blood chemistries (electrolytes, glucose, creatinine)

Urinalysis

Lipid profile

Electrocardiogram

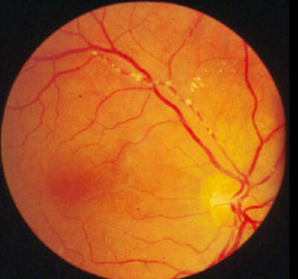

Physical exam of the patient with identified essential hypertension should specifically look for evidence of end-organ damage.

Fundoscopic signs of end-organ damage include:

Arteriovenous nicking (apparent retinal-vein narrowing secondary to arterial wall thickening)

Cotton-wool spots

Retinal flame hemorrhages

Auscultation of the heart may reveal a loud S2 and classically a S4 component ('Tennessee gallop'), though a S3 may be present as well or instead. A left ventricular heave may indicate left ventricular hypertrophy.

Untreated or poorly treated hypertension increases the risk of:

Coronary artery disease (CAD)

Stroke

Aortic dissection

Congestive heart failure

Kidney disease

Vision impairment

Lifestyle modifications are the initial treatment for primary hypertension. In order of most to least effective, these include:

Weight loss (in obese patients)

DASH diet

Exercise

Salt restriction

Reduced alcohol consumption

Note that on NBME examinations, the cheapest option that is still an acceptable form of accomplishing the indicated step in management is USUALLY the correct answer.

According to the Joint National Committee (JNC 8), any of the following are an appropriate initial drug of choice for the treatment of primary hypertension:

Thiazide diuretic (e.g. hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone)

Ca2+ channel blocker (e.g. amlodipine)

Angiotensin-converting enzyme(ACE) inhibitors (e.g. lisinopril)

Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) (e.g. losartan)

Patients with history of proteinuria in the setting of chronic kidney disease should receive an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) as initial monotherapy.

Once a medication has been initiated, it should be titrated to achieve the goal blood pressure (i.e. patient is no longer hypertensive) up to the maximum dose before adding a second medication.

Black patients on ACE inhibitor monotherapy historically have had smaller blood pressure reductions compared to white patients. Therefore, ACE inhibitors should be avoided as the initial drug of choice. ACE inhibitors may be added for combination therapy or if monotherapy is insufficient.

If a patient's hypertension is not controlled on the maximum dosage of the initial drug, a second drug from a different class (i.e. calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor or ARB, thiazide diuretic) should be added and titrated to effect. Note that an ACE inhibitor and an ARB count as the same drug class for the purpose of hypertensive pharmacotherapy.

If a patient's hypertension is not controlled on the maximum dosages of two drugs, a third drug from a different class (i.e. calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor or ARB, thiazide diuretic) should be added and titrated to effect. Note that an ACE inhibitor and an ARB count as the same drug class for the purpose of hypertensive pharmacotherapy.

If a patient's hypertension is not controlled on the maximum dosages of three drugs, additional antihypertensive agents are indicated, and the patient requires referral to a hypertensive specialist. Note that when a patient's hypertension is resistant to triple therapy there is very likely an underlying etiology present, such as renal artery stenosis.

Hypotension

Hypotension is abnormally low blood pressure which is a pathological deviation from an individual's physiologic baseline, but is generally defined as a systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure <60 mmHg.

Individuals who regularly engage in intense physical training may normally exhibit a low blood pressure at rest.

Several common causes of hypotension to consider include:

Hypovolemia, which may be due to hemorrhage, increased fluid loss (e.g. diarrhea, vomiting), increased insensible losses (e.g. a febrile patient), and insufficient fluid replacement--this is the most common cause of hypotension!

Medications--especially calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, alpha-antagonists, and diuretics.

Decreased cardiac output, as in cardiogenic shock, MI, or heart failure.

Decreased systemic vascular resistance, as in sepsis or severe metabolic acidosis.

Anemia

Hemodynamic redistribution, as in orthostatic hypotension, anaphylaxis, or neurogenic shock.

Lightheadedness and dizziness are cardinal signs of hypotension though other presenting symptoms may include:

Cool, clammy skin

Diaphoresis

Blurry vision

If the hypotension is sufficiently severe, syncope and seizures may occur

Evaluation of the hypotensive patient should begin with a repeat blood pressure measurement in both upper extremities, followed by a search for the underlying cause if the hypotension is validated.

A deviation of as little as 20 mm Hg below an individual’s baseline blood pressure can result in lightheadedness and syncope.

Hypotension of unknown etiology should be evaluated with:

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Complete blood count (CBC)

Basic metabolic profile (BMP)

Serum lactate

The following steps should be taken in the resuscitation of a hypotensive patient:

Fluid challenge

Pharmacologic pressure support (e.g. norepinephrine, epinephrine, phenylephrine, vasopressin, etc.)

Pharmacologic inotropic support (e.g. dopamine, dobutamine, milrinone, etc.).

Consider transfusing packed red blood cells (PRBCs) for a Hgb < 7 g.

Mechanical blood pressure support systems such as an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP)

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is the chronic inflammatory response to lipid accumulation in the intimal layer of arterial walls which over time leads to progressive hardening of the artery, loss of elasticity, and plaque formation.

The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis occurs in 3 steps:

Lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) accumulate in the intimal layer at sites of minor vascular trauma beginning early in life, leading to formation of the fatty streak.

Plaque progression occurs as smooth muscle cells migrate into the intima in response to cytokines, de-differentiate into fibroblasts, and proliferate.

Plaque disruption may occur if the overlying endothelial layer is damaged, resulting in thrombus formation with the potential for embolization.

Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of myocardial infarctions (90%) and strokes (60%), leading to most cases of heart failure and approximately one third of dementia diagnoses.

Important risk factors for atherosclerosis include:

Family history of coronary artery disease

Cigarette smoking

High LDL

Low HDL

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Hypertension

Obesity

It is important to recognize modifiable risk factors for the Step 2 CK.

Cigarette smoking is the most important modifiable risk factor for atherosclerosis-related heart disease.

Homocysteinemia is strongly associated with an increased rate of atherosclerotic events and disease progression. This is most commonly due to either vitamin B12 (cobalamin) or folate deficiency, but may also occur in the setting of congenital homocystinuria. In the former case, look for additional signs and symptoms of B12 or folate deficiency (neuropathy, multilobular polymorphonuclear cells, megaloblastic anemia, etc.); in the latter case, look for a patient with a marfanoid body habitus and cardiovascular disease at a young age. While controversial, some studies (and at least one USMLE World question) indicate that vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency can contribute to clinically significant alteration in homocysteine metabolism.

Large and medium-sized muscular arteries are the primary sites of atherosclerosis.

The most commonly affected vessels, in decreasing order of frequency of involvement, are:

Abdominal aorta

Coronary arteries

Popliteal artery

Internal carotid artery

Circle of Willis

Clinical presentation is dependent on the severity of ischemia, the degree of luminal occlusion, and the location of involvement.

Involvement of coronary arteries leads to myocardial infarction.

Internal carotid involvement causes transient ischemic attack (TIA) and stroke.

Atherosclerosis of the renal arteries is an important cause of secondary hypertension.

Peripheral artery involvement causes vascular insufficiency, intermittent claudication, and gangrene.

Visceral atherosclerosis leads to mesenteric ischemia.

The diagnosis of atherosclerosis is most often made by clinical manifestations of ischemia in conjunction with angiography demonstrating luminal narrowing.

Treatment of atherosclerosis is primarily oriented to managing modifiable risk factors.

The initial therapy for a new patient with risk factors and/or evidence of atherosclerotic disease is always lifestyle interventions such as smoking cessation, reducing dietary cholesterol, blood glucose and pressure control, and weight loss.

Patients without multiple risk factors who fail management with lifestyle modification after 3-6 months should begin statin therapy. Some patients with significant risk factors may be best treated with pharmacotherapy initially--see Hypercholesterolemia.

Dyslipidemia

Hypercholesterolemia is defined as an excess of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) (>130 mg/dL) or insufficient high-density lipoproteins (HDL) (<40 mg/dL).

See Lipid Digestion and Metabolism and Familial Hyperlipidemias for a review of lipid metabolism its derangements.

The LDL-C level reported in the lipid profile is an estimation based on the formula:

Hypercholesterolemia is multifactorial with a significant genetic component; however, additional factors which contribute to an elevated LDL-C level and lower HDL-C level include the following:

Obesity

Diabetes mellitus

Tobacco use

Alcohol abuse

Diets high in fatty foods

Increased estrogen exposure (including oral contraceptive pills)

Certain medications (see below)

Medications which can contribute to an elevated LDL-C level include:

Thiazide diuretics

Cyclosporine

Glucocorticoids

Amiodarone

Secondary causes of elevated LDL-C include 'REHAAB':

Renal disorders: nephrotic syndrome, uremia

Endocrine disorders: hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, Cushing's syndrome

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Anorexia nervosa

Acute intermittent porphyria

Biliary stasis

Several secondary causes of reduced HDL-C include malnutrition, Gaucher’s disease, and drugs (anabolic steroids, beta blockers).

Most dyslipidemia is diagnosed in an otherwise asymptomatic patient as part of routine screening.

Classic physical signs of dyslipidemia include:

Xanthelasmas: lipid deposits around the eyelids, seen in familial hypercholesterolemia (high LDL-C)

Xanthomas: lipid deposits on the trunk (eruptive--seen in familial hypertriglyceridemia), within extensor tendons (tendinous--seen familial hypercholesterolemia), and on extensor surfaces (tuberous--seen with elevated LDL-C or triglycerides)

Retinal cholesterol emboli

Corneal arcus

Patients with extremely elevated triglyceride levels are at risk for pancreatitis.

Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) task force guidelines recommend screening for dyslipidemia with lipid profiles every five years beginning at 35 years of age in low-risk men and 45 years of age in low-risk women.

There is currently no consensus guideline regarding the age at which regular lipid testing should be implemented in higher-risk individuals; however, frequently stated ages are 20-25 years of age for high-risk men and 20-35 years of age for high-risk women.

Additionally, initial screening is appropriate in certain pediatric patients. Please refer to the Adolescent Health Screening topic card under Pediatrics.

Healthy lifestyle changes including exercise programs, weight reduction, decreasing dietary fat intake, and smoking cessationshould be recommended to _all_patients, and are considered to be the foundation of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk-reduction.

Pharmacologic intervention with a statin is recommended for four groups of patients:

Primary prevention of ASCVD in patients 21 years of age and older with LDL-C ≥ 190.

Primary prevention of ASCVD in patients at least 45 years of age and less than 75 years of age with diabetes mellitus and an LDL-C of at least 70.

Primary prevention of ASCVD in patients at least 45 years of age and less than 75 years of age without diabetes mellitus or history of clinical ASCVD and with LDL-C between 70 and 189 who have a ten-year ASCVD risk greater than or equal to 7.5%.

Secondary prevention in patients with clinical ASCVD (previous myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular attack, or peripheral arterial disease).

The initiation of statin therapy _in addition to lifestyle modifications_is the best initial approach to management for these patients.

The current ACC/AHA guidelines state that the use of non-statin agents did not provide any significant reduction in ASCVD risk once LDL-C goals had been achieved; however, the use of non-statin agents may be appropriate in patients with an unsatisfactory response to statins, in patients who cannot tolerate statin therapy or for whom statins are contraindicated, and/or patients with a genetic dyslipidemia syndrome. Several of these non-statin agents are reviewed in the accompanying chart. Note that these agents do commonly appear in test questions.

Cardiac Arrythmia

SVT

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) refers to any tachyarrhythmia that arises from a pacemaker above the Bundle of His and is characterized as a narrow QRS complex on electrocardiogram (ECG).

Paroxysmal SVT is a term used to describe SVTs characterized by an abrupt onset and termination which are generally the result of reentry circuits, though the actual mechanisms are diverse.

SVTs include many different tachyarrhthmias:

Sinus tachycardia

Atrial tachycardia

Atrial flutter

Atrial fibrillation

Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT)

Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT)

Atrioventricular reentrant/reciprocating tachycardia (AVRT)

Junctional tachycardia

Sinus tachycardia is rhythm originating in the sinoatrial node which exhibits 1:1 atrioventricular (AV) conduction (P before every QRS, QRS following every P) with a regular rate of >100 beats per minute.

Physiologic sinus tachycardia occurs in normal subjects with an increase in sympathetic tone (exercise, emotions, pain), alcohol use, caffeine ingestion, and certain drugs such as those with anticholinergic or beta-adrenergic agonist effects.

Possible pathologic causes of sinus tachycardia include:

Fever secondary to systemic illness

Hypotension, hypovolemia, or shock

Anemia

Thyrotoxicosis

Heart failure or myocardial infarction (MI)

Pulmonary embolism (Note that the most common ECG finding in the setting of pulmonary embolism is indeed sinus tachycardia--a frequently tested and pimped point.)

The diagnosis is made on review of an ECG demonstrating a sinus rhythm of greater than 100 BPM.

Treatment is directed at underlying causes (e.g. antipyretics if the cause is fever). Beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers may be considered for overly symptomatic patients.

Follow the links below to review several examples of sinus tachycardia.

Sinus tachycardia - example 1

Sinus tachycardia - example 2 - Note the saw-tooth appearance of the wave-form in leads II and V3--do not allow yourself to mistake this for 2:1 atrial flutter. Several tips to distinguish sinus tachycardia (as in this example) vs. 2:1 atrial flutter (as, for example, in this tracing) are to look for regular distortion of the PR and ST segments and negatively deflected flutter waves in the inferior leads. This webpage is dedicated to the diagnosis of 2:1 flutter. It may be more than necessary for Step 2 CK purposes, but great if you wind up in the CCU during clerkships.

Most patients with symptomatic SVT complain of palpitations, dizziness, chest pain, diaphoresis, and/or shortness of breath.

Some patients with SVT may experience hemodynamic instability with insufficient forward cardiac output, requiring emergent direct currect electrical cardioversion.

Electrophysiological testing is the gold standard and can help identify bypass tracts and aberrant conduction systems, but is often not necessary since electrocardiogram (ECG) is usually sufficient to diagnose SVT and PSVT.

General electrocardiographic features of SVT include ventricular rate > 100 bpm with narrow QRS complexes (<120 ms).

Laboratory tests including electrolyte levels, CBC, TSH, and digoxin levels are helpful in ruling out contributing conditions.

The best initial treatment of SVT in stable patients is carotid massage or vagal maneuvers (e.g. breath holding, Valsalva, urination), as these help slow AV nodal conduction by increasing parasympathetic tone.

When vagal maneuvers do not help, the next step in therapy is adenosine. Adenosine directly blocks the AV node to help interrupt the reentrant circuit. Verapamil can also be used for this purpose.

Direct current (DC) cardioversion is the preferred treatment of SVT in patients who are hemodynamically unstable (hypotension, pulmonary edema, and altered mental status).

VFIB

Ventricular fibrillation is the most serious cardiac arrhythmia, characterized by rapid, uncoordinated quivering contractions of the ventricles.

Ventricular fibrillation is most commonly associated with coronary artery disease. Other common risk factors include myocardial infarction, decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, electrolyte disturbance, long QT syndrome, and atrial fibrillation.

Ventricular fibrillation is the most common cause of mortality in patients suffering from an acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Patients with ventricular fibrillation classically present with a sudden loss of consciousness or a comatose state. Some patients may present with symptoms (chest pain, diaphoresis) of a myocardial infarction prior to loss of consciousness.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) of patients with ventricular fibrillation reveals chaotic waveforms without the presence of P waves, QRS complexes, or T waves.

Concurrent serum laboratory tests (e.g. cardiac enzymes, potassium, calcium, magnesium, TSH, BNP, and toxicology) are extremely important to help determine the etiology.

Ventricular fibrillation results in insufficient forward cardiac output with hemodynamic collapse, leading quickly to ischemic central nervous system damage, myocardial injury, and death.

Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) should be implemented in the setting of ventricular fibrillation: ventricular fibrillation is a shockable rhythm and a defibrillating shock should be delivered as soon as possible, followed by chest compressions for two minutes while peripheral access is established.

After two rounds of defibrillation without restoration of a stable rhythm, epinephrine (1 mg bolus) should be administered followed by another shock. 1 mg boluses of epinephrine should be delivered every 3 to 5 minutes thereafter.

In patients refractory to three rounds of defibrillation plus epinephrine, amiodarone (300 mg IV bolus) can be delivered in anticipation of a fourth shock, as this may lower the defibrillation threshold.

Note that asystole and pulseless electrical activity (electromechanical dissociation) are NOT shockable arrhythmias. All patients in cardiopulmonary arrest should have a defibrillator attached, but if either of these conditions is present then the best approach is immediate high-quality chest compressions.

Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia is a run of 3 or more consecutive premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) which spontaneously resolves in 30 seconds or less, and thus generally does not require treatment.

VTACH

Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia is typically the result of intraventricular re-entry circuits which arise when ischemic conditions alter the electrophysiological properties of the ventricular myocardium. Additional causes can include:

Infarct scarring

Acute myocardial infarction

Cardiomyopathies

Myocarditis

Drugs (cocaine)

Electrolyte disturbances

Sustained ventricular tachycardia consists of ectopic ventricular beats which occur consecutively for more than 30 seconds. Sustained ventricular tachycardia is a medical emergency, requiring immediate treatment!

The most common cause of emergent ventricular tachycardia is coronary artery disease, and it is the most common cause of death due to myocardial infarction (MI).

The clinical presentation of ventricular tachycardia ranges from asymptomatic (usually chronic) to hemodynamic compromise requiring immediate electrical cardioversion.

The characteristic appearance of ventricular tachycardia on ECG is wide, regular QRS tachycardia with QRS complexes lasting longer than 140 msec.

Note that additional wide-complex tachycardias (supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) with aberrancy, atrial tachyarrhythmia in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, SVT with preexisting bundle branch block (BBB), etc.) may mimic VT, and are sometimes distinguished on the basis of the response to antiarrhythmic medication; however, all patients with hemodynamic compromise due to wide-complex tachycardia require immediate direct-current cardioversion regardless of the etiology.

The Brugada Criteria sets parameters to diagnose VT. If ANY of these criteria are met, then the rhythm is ventricular tachycardia:

No RS complex in any precordial leads

An R-to-S interval >100 ms in any precordial lead

Atrioventricular dissociation (p waves are regular but not related to the rate of QRS complexes)

Leads V1, V2 and V6 fulfilling classic criteria for ventricular tachycardia.

If NONE of these criteria are met, the rhythm is likely a wide-complex supraventricular tachycardia.

If hemodynamic compromise is present, immediate high-quality chest compressions and direct-current electrical cardioversion are indicated.

See ACLS: Cardiac Arrest for more information.

If the patient is hemodynamically stable, elective cardioversion with lidocaine, class IA antiarrhythmics, or amiodarone may be indicated for the treatment of sustained ventricular tachycardia.

AFIB

Atrial fibrillation refers to the quivering state of the atria that occurs when many ectopic atrial foci fire in a chaotic manner that prevents the normal coordinated atrial contraction.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac arrhythmia.

The single most important risk factor for atrial fibrillation is mitral stenosis.

Atrial fibrillation may be the presenting symptom of hyperthyroidism.

The atrioventricular (AV) node only conducts some of the atrial impulses through to the ventricles, resulting in the classic irregularly irregular rhythm. Though atrial rate may exceed 500 bpm, the ventricular rate is typically 120-180 bpm.

Ectopic foci around the pulmonic veins are most often implicated in the generation of atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation leads to a rapid and irregular heartbeat, which in turn causes palpitations and exercise intolerance. Since the “quivering” atria are unable to pump blood effectively, venous stasis may lead to congestive symptoms such as shortness of breath and edema.

An EKG reveals an irregularly irregular rhythm with a disorganized baseline electrical activity, the absence of p-waves, and narrow QRS complexes (since the signal originates above the AV node).

Because the blood pressure varies from beat to beat, digital blood pressure machines often have trouble getting accurate measurements in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Laboratory workup should include, at a minimum:

Testing for renal function

Electrolytes

TSH

CBC

PT/INR

Complications of atrial fibrillation arise from reduced cardiac output (loss of the atrial kick greatly reduces preload), increased cardiac oxygen demand, and thromboembolism secondary to atrial stasis.

Because the atria quiver instead of contracting, stagnant blood in the atrium may clot, leading to embolic events such as a stroke. This is most likely to occur in a region called the left atrial appendage. (Because patients with intermittent atrial fibrillation may experience return of the atrial kick, they may be more likely to embolize clots that form).

Myocardial infarction may arise secondary to increased cardiac oxygen demand.

Reduced cardiac output may lead to symptoms of congestive heart failure, such as pulmonary or lower extremity edema.

Cardioversion to sinus rhythm is indicated for the treatment of atrial fibrillation in the following settings:

For the treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation which continues despite the ventricular rate having been controlled with a beta-blocker or a calcium channel blocker.

For first-time occurrence of atrial fibrillation, but only if the onset is known to be within the past 2 days or if the patient has been anticoagulated for at least 3 weeks. (Patients must also be anticoagulated for 4 weeks after cardioversion).

In the setting of hemodynamic instability.

Note that the second point is extremely important and frequently tested with the 'next best step in management' type of question.

Chemical (pharmacologic) cardioversion from atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm may be attempted chemically via class IC (propafenone, flecainide), or class III (ibutilide, dofetilide > amiodarone, sotalol) antiarrhythmic drugs.

Electrical cardioversion to sinus rhythm from atrial fibrillation may be attempted by the delivery of direct current (DC) voltage synchronized with the QRS complex.

Management strategies for atrial fibrillation may include rate control and/or rhythm control. Anticoagulation is added to prevent stroke and thromboembolism.

Warfarin is the medication of choice to prevent stroke in atrial fibrillation and the only medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of valve-related atrial fibrillation, but newer anticoagulants such as dabigatran and apixaban may be used in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Recall that anticoagulants are not the same as antiplatelet medications such as aspirin and clopidogrel (Plavix).

Coagulation studies (aPTT/INR) should be ordered before beginning anticoagulant therapy. INR is used in clinical practice to monitor warfarin levels; however, warfarin will cause a prolongation of both PT/INR as well as aPTT.

Ventricular rate control is achieved using beta blockers (class II antiarrhythmics) or calcium channel blockers (diltiazem, verapamil--class IV antiarrhythmics), which slow conduction from the fibrillating atria to the ventricles. This strategy is generally employed in patients older than 65.

Rhythm control is achieved using antiarrhythmic agents such as amiodarone, propafenone, dofetilide, flecainide, or sotalol, which alter the cardiac action potential in such a way that helps maintain sinus rhythm.

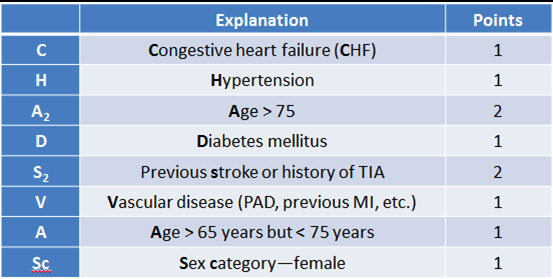

Several calculations are available to estimate the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. These include the CHADS, CHADS2, and CHA2DS2-VASc. The CHA2DS2-VASc is the most current, and is summarized in the included table. Generally, anticoagulation is indicated for a score of 2 or greater. Aspirin monotherapy has not been demonstrated to offer significant protection against ischemic stroke for patients with low risk (CHA2DS2-VASc score < 2).

[Gregory et al. Chest. 2013;137:263-72.] [Lane, Lip. Circulation. 2012;126:860-5.]

AFLUT

Atrial Flutter is a type of supraventricular tachycardia which arises due to a macro-reentry circuit within the atrium (most commonly involving irritable foci in the right atrium near the tricuspid annulus) and is characterized by an atrial rate 250-350 BPM (classically 300 BPM).

Since the atrioventricular (AV) node has a slower conduction rate than the atrial muscle, only some of the atrial depolarizations are conducted to the ventricles, resulting in a functional AV block.The ratio of atrial to ventricular depolarizations is used to describe the rhythm (i.e. atrial rate of 340 bpm and a ventricular rate of 170 bpm would be described as a 2:1 flutter).

Atrial flutter usually occurs in the following settings:

Coronary artery disease (CAD)

Thyrotoxicosis

Mitral valve disease

Cardiac surgery

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Pulmonary embolism

Pericarditis

Generally anything that causes atrial fibrillation can cause atrial flutter.

The classic presentation of atrial flutter consists of palpitations with a rapid heart rate. While atrial flutter is often asymptomatic in otherwise healthy patients, patients with underlying heart disease may develop symptoms related to decreased cardiac output early in the disease.

On physical exam, patients with atrial flutter will have a rapid but mostly regular heart rate with a pulse usually in the range of 120-180 bpm.

Atrial flutter is recognized on electrocardiogram (ECG) by regular, sawtooth flutter waves of atrial contraction at a rate of 250-350 bpm with a ventricular response rate of approximately 180 bpm. These flutter waves are most easily seen in the inferior leads, as well as V2.

Follow the links below to review several examples of atrial flutter.

Atrial flutter - example 1 (2:1 conduction) Refer to the above discussion under sinus tachycardia examples regarding distinguishing sinus tachycardia vs. 2:1 flutter.

Atrial flutter - example 2 (3:1 conduction)

Atrial flutter - example 3 (4:1 conduction)

Persistent, untreated atrial flutter often degenerates into atrial fibrillation.

The additional strain on the heart associated with atrial flutter predisposes the patient to the same pathophysiology as atrial fibrillation:

Cardiac ischemia

Dizziness and/or syncope, secondary to diminished forward output

Decompensated heart failure, particularly in patients with preexisting cardiac disease

As in atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter that creates ineffective contraction of the atria can promote thrombus formation and predispose to thromboembolic events.

Medical management of persistent atrial flutter is the same as atrial fibrillation and includes anticoagulation and rate and/or rhythm control with direct current electrical cardioversion for patients who are hemodynamically unstable.

Atrial flutter often recurs, so ablation is generally recommended. This procedure involves mapping the re-entrant circuit that is causing the flutter rhythm, then creating a line of scar tissue that disrupts conduction through the circuit. Recall that this is usually tissue in the vicinity of the tricuspid annulus.

Long QT

Pathogenesis

Etiologies of acquired long QT syndrome include:

Drugs

Electrolyte imbalance

Myocardial infarction

Remember the mnemonic for drugs that can cause Torsades de pointes: ABCDE

AntiArrhythmics (class IA - especially quinidine & class III)

AntiBiotics (e.g. macrolides)

Anti"C"ychotics (e.g. haloperidol)

AntiDepressants (e.g. TCAs)

AntiEmetics (e.g. ondansetron)

Additionally, methadone, cisapride and arsenic trioxide can cause Torsades de pointes.

Drugs that are known to cause acquired long QT syndrome have the effect of blocking the cardiac $I_K$ current mediated potassium channel of the heart, that is, the rectifying potassium current which is responsible for the repolarization to resting membrane equilibrium potential. Low serum potassium can make this effect worse.

Specific electrolyte imbalances known to cause acquired long QT syndrome include:

Hypokalemia

Hypomagnesemia

Hypocalcemia

Note: low serum potassium can enhance a drug's inhibition of the cardiac IKr current.

Prolonged QT is diagnosed by ECG. QTc is the corrected QT interval, which is defined as the QT interval divided by the square root of the RR interval: $QTc=QT/\sqrt{RR}$ ; however, QTc is more easily estimated by checking that the QT is less than half of the RR. The normal QTc value is less than 440 milliseconds.

Torsades de pointes (TdP), a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, is a life threatening complication of QT prolongation.

Management

The management of acquired long QT syndrome depends on the specific cause, which can include:

Stopping the offending drug if drug induced

Correcting any electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia)

IV magnesium sulfate if the patient develops TdP

AVNRT

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia (AVNRT) is a type of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) which originates within the AV node.

The basis for AVNRT is the existence of two separate conduction pathways within the AV node: a slow pathway with a short refractory period and a fast pathway with a long refractory period which share a final common pathway.

In sinus rhythm, the sinoatrial impulse arrives at the AV node and conducts down both pathways simultaneously. Usually by the time the impulse traverses the slow pathway, the fast pathway is still refractory, so the impulse is extinguished.

In the common form of AVNRT, a perfectly-timed premature atrial beat arrives while the fast pathway is refractory and the slow pathway is able to conduct, thus allowing a re-entry circuit to develop if the fast pathway has recovered by the time the impulse traverses the slow pathway:

The impulse conducts down the slow pathway _but not the fast pathway, which is refractory.

The fast pathway recovers while the impulse traverses the slow pathway.

The impulse arrives at the final common pathway and proceeds in a retrograde fashion up the fast pathway, which results in retrograde atrial depolarization.

The slow pathway recovers and re-conducts the impulse to the ventricles.

AVNRT occurs mostly in young patients with healthy hearts.

AVNRT presents with the same symptoms as most SVTs:

Sudden onset tachycardia (sensation of heart racing)

Palpitations

Dizziness

Dyspnea

Chest discomfort

Presyncope/syncope

Electrocardiogram (ECG) will show a narrow-complex tachycardia (unless pre-existing BBB or aberrant ventricular conduction exists). Retrograde P-waves are present, but are often buried in or fused to the QRS complex.

ECG in between episodes of AVNRT will be the normal baseline ECG for that patient--that is, there is NO ventricular pre-excitation or characteristic ECG abnormality as there is in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Management

The long-term management of AVNRT involves, in the following order:

Rate control with diltiazem, verapamil, or a beta-blocker;

Rhythm control with antiarrhythmic drugs such as flecainide or propafenone (Class IC); and

Radiocatheter ablation for symptomatic patients failing previously-mentioned treatments.

Acute symptomatic AVNRT is best managed in the same manner as other symptomatic SVTs: if initial vagal maneuvers and carotid massage fail to restore normal sinus rhythm, administration of IV adenosine or verapamil is indicated. If at any point the patient develops signs of hemodynamic instability, direct current (DC) cardioversion should be performed immediately.

Multifocal Atrial Tachycardia

Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT) is an irregularly-irregular supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) characterized by the presence of 3 or more ectopic atrial pacemaking foci.

MAT occurs more commonly in patients with COPD, hypoxemia, and underlying pulmonary dysfunction. Other Less common etiological factors include hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, sepsis, and theophylline or digitalis toxicity.

Most patients found to have MAT present with symptoms of an underlying pulmonary condition (e.g. shortness of breath, productive cough, chest pain). Only rarely do patients present with primary complaints of palpitations or syncopal episodes.

The best diagnostic test is an electrocardiogram (ECG), which will show an (irregularly) irregular rhythm with an atrial rate greater than 100 bpm and at least 3 morphologically distinct P waves on the same lead.

An ECG of MAT has the following defining features:

An atrial rate of 100-200 BPM

At least three morphologically distinct P waves occurring on the same lead

P waves return to baseline

P-P intervals, P-R duration, and R-R intervals vary

Some P waves may not be conducted, but every QRS complex is preceded by a P wave

MAT can be suspected in patients with an irregular, rapid pulse and a history of pulmonary disease.

Treatment of MAT should be directed first at the patient's underlying condition: electrolyte abnormalities should be addressed and potentially offending medications removed.

Symptomatic MAT is best managed with rate control via verapamil or cardio-selective beta blockers (e.g. metoprolol, esmolol), which allows the heart to pump more efficiently and allows for better oxygenation.

There is no role for electrical cardioversion or rhythm control with antiarrhythmics.

For patients with ongoing, symptomatic MAT who cannot tolerate pharmacologic rate control, radiocatheter ablation of the AV node and concomitant pacemaker placement provide a final means of relief.

WPW

In Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome a separate accessory pathway known as the Bundle of Kentis present between the atria and ventricles which allows aberrant conduction between the atria and ventricles to bypass the AV node.

The accessory Bundle of Kent conducts atrial impulses to the level of the ventriclesfasterthan the AV node, which naturally delays AV conduction.

WPW syndrome is the basis for atrioventricular(AV) reentry/reciprocating tachycardia (AVRT), a type of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

In orthodromic AVRT, the most common type of AVRT, the reentry circuit involves forward conduction of atrial impulses to the ventricles via the AV node with retrograde conduction from the ventricles back up to the atria via the accessory pathway.

In antidromic AVRT, the less common type of AVRT, the reentry circuit involves forward conduction down the accessory pathway with retrograde conduction up the His-Purkinje system through the AV node.

The result of the different AV conduction velocities in patients with an accessory Kent bundle is ventricular preexcitation, which is seen as a delta wave (see image) on electrocardiogram (ECG) of a patient with an accessory Kent bundle in sinus rhythm.

Symptomatic AVRT presents in the same manner as most SVTs:

Sudden onset tachycardia (sensation of heart racing)

Palpitations

Dizziness

Dyspnea

Chest discomfort

Presyncope/syncope

Orthodromic AVRT produces a regular, narrow-complex tachycardia with a ventricular rate of 150-250 BPM(may be greater) and inverted P waves on ECG. Sometimes there is a beat-to-beat oscillation in the QRS amplitude, a finding known as electrical QRS alternans, which is more commonly associated with pericardial effusion.

Antidromic AVRT produces a regular, wide-complex tachycardiawith a ventricular rate of 150-250 BPM with inverted P waves on ECG, which may be confused with ventricular tachycardia.

The management of symptomatic orthodromic AVRT in hemodynamically stable patients is first vagal maneuvers. If unsuccessful, then AV-nodal blocking agents (IV adenosine preferred over IV verapamil), and immediate direct current (DC) cardioversion for hemodynamically unstable patients.

AV nodal blocking agents such as adenosine, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers (especially verapamil), and digoxin should not be used for AF in patients with WPW as they may promote conduction across the accessory pathway and lead to degeneration of AF into VF.

The management of symptomatic antidromic AVRT in hemodynamically stable patients is with IV procainamide.

Definitive management of AVRT is radiocatheter ablation of the accessory Bundle of Kent.

Bradycardia

Sinus bradycardia is a regular sinus rhythm characterized by a resting heart rate of < 60 BPM.

Physiologic sinus bradycardia can be caused by sleep, athletic conditioning, and normal vagal activity.

Pathological sinus bradycardia may be caused by:

Exaggerated vagal tone

Sinoatrial (SA) node ischemia (e.g. myocardial infarction in the right coronary artery (RCA) distribution)

Sick sinus syndrome

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

Hypothyroidism

Hypothermia

Medications (e.g. calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers)

Sinus bradycardia is usually asymptomatic, especially in the conditioned athlete; however, progressive pathological bradycardia may result in fatigue, presyncope, or syncope.

Treatment is NOT indicated in asymptomatic patients with sinus bradycardia. Management of symptomatic patients involves removing offending agents and treating underlying causes when these are present. Pacemakers should be considered for patients with intrinsic SA node damage.

Sick Sinus

Sick Sinus Syndrome (SSS) is the condition characterized by chronic SA node dysfunction (marked bradycardia, sinus pause/arrest, sinoatrial block) secondary to senescence of the node and surrounding myocardium.

SSS is most commonly associated with SA node ischemia, such as might occur secondary to a proximal right coronary artery (RCA) infarction (see Coronary Anatomy). Other causes include inflammatory processes or infiltrative diseases that involve the SA node.

Sick sinus syndrome generally presents in older patients who have multiple comorbidities and high mortality rates with:

Chronic and often severe bradycardia

Sinus pauses, sinus arrest, and SA nodal exit block

Tachy-brady syndrome--alternating bouts of bradycardia and atrial tachyarrhythmias (most commonly atrial fibrillation)

Patients may complain of lightheadedness, syncope, exertional dyspnea, and worsening angina.

The diagnosis is often clinical, with the characteristic symptoms and accompanying signs being the major clue. An ECG is always obtained but is nonspecific. Look for marked sinus bradycardia (p waves present) with occasional dropped beats (absent p-qrs-t), supraventricular escape rhythms, atrial fibrillation (i.e. the tachy-brady syndrome), and evidence of localized ischemia (especially in the RCA territory).

Symptomatic bradycardia in the setting of sick sinus syndrome is an indication for pacemaker placement. Pharmacological treatment of tachyarrhythmias with beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and/or digoxin should be considered; however, these medications may exacerbate sinus bradycardia. Note that while lightheadedness and syncope are reversed in almost all patients following pacemaker placement, there does not seem to be a survival benefit.

[Birnie D, Williams K, Guo A, et al. Reasons for escalating pacemaker implants. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:93.]

Junctional Rhythm

Junctional rhythm or AV nodal rhythm is a pathological bradycardic rhythm that occurs when the SA node fails to fire at a normal rate. It is often called a “junctional escape rhythm” because the AV node “escapes” from the pacing of the SA node, which normally fires with a faster intrinsic rate to serve as the primary pacemaker of the heart and override lower pacemakers.

Junctional escape rhythms most commonly arise in the setting of profound SA node dysfunction, when the degree of sinus bradycardia is below the intrinsic rate of the SA node. These bradyarrhythmias occur at a characteristic rate of 40-60 BPM, which is the intrinsic rate of the AV node. (Less commonly, in the setting of abnormally increased junctional automaticity, junctional tachycardia may out-pace a normal sinus rate. This can occur in the setting of digitalis toxicity, recent cardiac surgery, acute myocardial infarction, or isoproterenol infusion.)

Patients will often be asymptomatic; however, lightheadedness and syncope can occur as a consequence of decreased ventricular filling and cardiac output secondary to uncoordinated contraction of the atria with the ventricles, and should prompt an electrocardiogram (ECG). The hallmark of junctional rhythms on ECG is the absence of P waves preceding the QRS complex. P waves may be incorporated in with or occur after the QRS complex, indicating retrograde depolarization of the SA node.

Treatment

The decision of whether or not to place a pacemaker for the treatment of bradycardia is guided by two main factors: (1) association of symptoms with arrhythmia and (2) the potential for progression of arrhythmia disturbance.

Class I indications for pacemaker placement in the management of sinus bradycardia include:

Symptomatic sinus bradycardia

Sinus bradycardia which prevents exercise (symptomatic chronotropic incompetence)

Symptomatic Mobitz I or II

Mobitz type II with widened QRS or chronic bifascicular block, regardless of symptoms