18 Nephrology

Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer is the most common malignancy involving the urinary system, with transitional (urothelial) cell carcinoma being the most common subtype.

Squamous cell carcinoma (associated with schistosomiasis) and adenocarcinoma occur less frequently.

Environmental exposures account for the majority of cases. Risks associated with bladder cancer include the following:

Smoking (most common)

Occupational exposure (e.g. painters, rubber industry, beauticians, and industrial factory workers)

Medications (e.g. cyclophosphamide)

Infections (e.g. HPV, Schistosomiasis)

Indwelling catheters and radiation overexposure (e.g. CT scans)

Men are 3X more likely to get bladder cancer than women.

Symptoms

The most common presenting symptom in bladder cancer is painless hematuria.

Other voiding symptoms such as dysuria, urge incontinence, and suprapubic pain may be present as well but don't typically occur until the disease is advanced.

Diagnosis

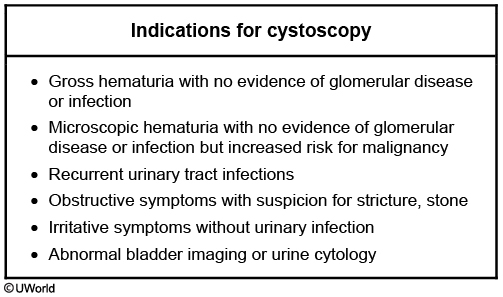

Fluorescence cystoscopy is the gold standard in diagnosing bladder cancer. Cystoscopy allows the diagnostician to directly visualize the inner bladder wall, perform urine cytology, and biopsy any suspicious lesions.

Urinalysis with urine culture is the best initial diagnostic modality when evaluating patients presenting with hematuria, which can help detect suspected infections and glomerular etiologies.

CT with and without contrast of the abdomen and pelvis is necessary to help define the exact location and extent of disease in patients with bladder cancer.

Treatment

Bladder cancer is divided into 3 categories: non-muscle invasive, muscle invasive bladder cancer, and metastatic disease. The extent of disease guides treatment protocols.

The best initial therapy for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer is transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) to help remove any abnormal tumor cells prior to intravesical therapy (i.e. BCG introduced into the bladder via catheter to prevent recurrence).

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) is the agent of choice for intravesical therapy. Note: This is the same organism that is used in the BCG vaccine against tuberculosis. It induces a local immune response within the bladder epithelium which helps to destroy cancerous cells and prevent recurrence.

Radical cystectomy with urinary diversion is the treatment of choice in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. In men, this includes the removal of the prostate, seminal vesicles, and urinary bladder. In women, this can include the removal of the anterior vagina, ovaries, uterus, cervix, and urinary bladder.

Pharmaceutical management of metastatic bladder cancer either involves the combination of methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC) or a combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC).

Dialysis

Dialysis is an artificial filtration system allowing fluid and toxin filtration from circulation when the kidneys are unable to do so. The process is completed by diffusion of the fluid across a semipermeable membrane.

The two types of dialysis are hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis (chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, CAPD).

Dialysis is most often considered in the setting of chronic kidney disease and/or acute kidney injury.

In chronic kidney disease, dialysis serves as a life-sustaining mechanism before kidney transplantation. In acute kidney injury dialysis is most-often temporary until normal renal function is restored.

Indications for dialysis can be broken down into emergent and non-emergent categories.

Emergent indications for dialysis can be remembered using the mnemonic LIDS:

Life-threatening volume overload (e.g. pulmonary edema, hypertensive emergency)

Intractable metabolic acidosis

Drug intoxication (e.g. methanol, ethylene glycol, lithium, aspirin)

Severe, refractory electrolyte abnormalities (e.g. hyperkalemia)

The most common non-emergent indication for dialysis is symptomatic uremia.

Absolute indications for dialysis can be remembered using the mnemonic AEIOU:

Acidosis

Electrolytes

Intoxications

Overload

Uremia

Hemodialysis is performed after establishing access either temporarily through a central catheter (subclavian, jugular vein) or permanently through an arteriovenous fistula (connecting the brachial or radial artery to a vein in the forearm).

Once access has been established, the patient’s blood is pumped through a dialyzer consisting of a network of semipermeable membranes (NOTE: blood must be heparinized to prevent clotting).

Patients typically undergo hemodialysis 3-5x/week.

Hemodialysis is considered more efficient than peritoneal dialysis but physiological differences from normal renal function may predispose the patient to hypotension and/or hypo-osmolality.

Other disadvantages of hemodialysis include:

sepsis from port-site infection

first-use syndrome (chest pain, back pain, possible anaphylaxis)

amyloidosis from beta-2 microglobin (in bones and joints)

Peritoneal dialysis relies on a temporary catheter giving access to the peritoneal fluid.

In peritoneal dialysis the peritoneum serves as the dialysis membrane.

Peritoneal dialysis is advantageous because it can be self-performed by the patient and it more accurately approximates normal renal physiology.

Disadvantages of peritoneal dialysis include: hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and peritonitis.

Because dialysis does not remedy the loss of renal synthetic function, supplementation with erythropoietin and vitamin D must be provided separately.

Hypernatremia

Hypernatremia is a serum Na+ concentration > 145 mEq/L.

Causes

Remember that a derangement of Na+ concentration is most commonly related to a problem with water homeostasis. The normal response to hypernatremia is to retain more water. So for hypernatremia to persist there must be an abnormality in the body's normal efforts to increase water.

Based on volume status, hypernatremia can either be hypervolemic, euvolemic or hypovolemic.

Hypervolemic

Hypervolemic hypernatremia is typically caused by a gain of both Na+ and water, but of more Na+ than water. Causes of hypervolemic hypernatremia include:

Exogenous glucocorticoids

Cushing's syndrome

Primary hyperaldosteronism

Euvolemic

Euvolemic hypernatremia results from loss of free water alone, without Na+ loss. The most common cause of euvolemic hypernatremia is diabetes insipidus.

Diabetes insipidus is central or nephrogenic. In central diabetes insipidus, vasopressin (ADH) secretion is impaired. In nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, the renal response to vasopressin is impaired.

Central DI can result from infections, encephalitis, meningitis, and trauma to the neurohypophysis.

Nephrogenic DI can be inherited or the result of renal injury. Causes of nephrogenic DI are many, and include:

Medications: lithium, demeclocycline

Electrolyte disorders: hypercalcemia, hypokalemia

Kidney disease: polycystic kidney disease, obstructive uropathy

Hypovolemic

Hypovolemic hypernatremia is typically caused by a loss of Na+ and water but more water than Na+. Hypovolemic hypernatremia can be due to renal loss (diuretics, osmotic diuresis, renal failure) or extrarenal loss (diarrhea, diaphoresis, respiratory).

Osmotic diuresis occurs whenever a high osmotic load in the renal tubules draws water which is then diuresed. Examples of non-Na+ osmotic diuresis are mannitol and glucosuria. In critically ill patients, elevated levels of urea can also cause osmotic diuresis and subsequent hypernatremia.

Extra-renal causes of water loss include evaporation from the skin and respiratory tract. Diarrhea can result in water loss out of proportion of Na+ loss.

Symptoms

Many symptoms of hypernatremia are neurologic. Hypernatremia results in water shifting from the intracellular to the extracellular space,resulting in neuron shrinkage.

Symptoms of hypernatremia include:

Altered mental status

Weakness

Increased thirst

Neuromuscular irritability

Seizures

Coma

Diagnosis

Assessing urine osmolality and the response to desmopressin (DDAVP) can help identify an underlying etiology for hypernatremia.

The normal response to hypernatremia is to excrete very concentrated urine (up to 1200 mOsm/L). Hypernatremia with a urine osmolality < 800 mOsm/L suggests a renal etiology.

Hypernatremia and urine osmolality <300 mOsm/L suggests complete DI.

DDAVP is an analog of vasopressin. Restricting water intake and administering DDAVP can differentiate between central and nephrogenic DI.

Water restriction test is contraindicated in polyuric patients where nephrogenic DI is highly suspected (e.g. infants and long-term lithium use) since it has the potential to worsen the hypernatremia.

If urine osmolality increases after DDAVP administration, it is central DI. If urine osmolality does not increase after DDAVP, it indicates that the kidneys do not respond properly to vasopressin and a diagnosis of nephrogenic DI is made.

Treatment

Similar to treatment of hyponatremia, the correction of hypernatremia should be gradual. The rate of correction of water deficit should not exceed 12 mEq/L in a 24 hour period.

The best treatment is oral or nasogastric administration of water. Dextrose in water can also be used.

If hypernatremic and hypovolemic, normal saline followed by 5% dextrose in water (0.45% normal saline may also be used, however 5% dextrose is preferred) can correct the Na+ and water deficit.

Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia is defined as a plasma concentration of Na+ <135 mEq/L.

The body responds to excess or insufficient water via renal mechanisms, maintaining a fairly constant Na+ concentration. In order to have an abnormal Na+ concentration, there needs to be a pathology in the way the body handles water. Disorders of Na+ concentration are really disorders of water balance.

Many symptoms of hyponatremia are neurologic due to a relative increase in intracellular osmolality relative to extracellular osmolality. As result, water shifts into cells in the CNS and can cause brain edema. Symptoms include:

Headache

Delirium

Weakness

Hypoactive deep tendon reflexes

Seizures, coma (once Na+ falls < 115 mEq/L)

Gastrointestinal symptoms of hyponatremia include:

Nausea/vomiting

Ileus

Watery diarrhea

Diagnosis

The most important initial step in evaluating a patient for hyponatremia is a history and physical. Lab tests can help identify an underlying etiology.

The first step in evaluation of hyponatremia is checking the plasma osmolarity. Plasma osmolality is normally low in hyponatremia. The exception is in the case of osmotically active solutes, such as glucose, sorbitol, and mannitol.

If true hyponatremia is identified (Osm < 280), extracellular volume should be assessed next. At this stage, hyponatremia may either be hypervolemic, euvolemic or hypovolemic.

Urine Na+ concentrations help identify hypovolemic hyponatremia as being due to renal or extra-renal causes, since normally the kidneys retain Na+ in response to hyponatremia.

Urine Na+ < than 10 mEq/L suggests that the hyponatremia is due to an extra-renal cause.

Urine Na+ > 20 mEq/L suggests Na+ wasting in the kidneys.

Hypertonic hyponatremia is caused by the presence of osmotically active substances (e.g. glucose, mannitol and glycerol).

Glucose is osmotically active, and it draws water into the extracellular space. Increased vascular volume increases diuresis, leading to hyponatremia.

Hyperglycemia can also lead to falsely low serum sodium levels by interfering with laboratory detection of sodium. To correct for this, a correction factor must be added to the measured serum sodium level. The corrected serum sodium can be calculated using the following equation:

Corrected serum sodium = Measured serum sodium + 0.016 * (Serum glucose – 100)

Ex: A patient presents to the emergency department with a serum glucose of 623 and a serum sodium of 132. The corrected serum sodium = 132 + 0.016 * (623 - 100) = 140.37

Hypervolemic

Hypervolemic hyponatremia may be caused by congestive heart failure (CHF), nephrotic syndrome or liver disease.

In most cases (CHF, nephrotic syndrome), the patient is “fluid overloaded” but the kidney is sensing a low perfusion state. That person will “hold on” to salt and water as they would if they were volume depleted: the kidney is sensing a state of low perfusion. The exception to this is seen in acute renal failure, in which the kidney is unable to reabsorb sodium appropriately from the urine and the patient will present with a high urine sodium.

Euvolemic

Euvolemic hyponatremia may be caused by:

SIADH

Psychogenic polydipsia

Hypothyroidism

Psychogenic polydipsia is the consumption of water in excess of the kidney’s ability to excrete free water, producing hyponatremia.

SIADH is the inappropriate secretion of ADH, increasing water retention and leading to hyponatremia. Non-medicine causes of SIADH include:

Organic CNS disease: meningitis, encephalitis, cerebrovascular accident, head trauma

Acute psychosis

Tumors, especially small cell lung cancer (paraneoplastic)

Other pulmonary diseases (pneumonia, acute respiratory failure)

Major pharmaceutical causes of SIADH include:

Vincristine

SSRIs (particularly in those > 65 y/o)

Chlorpropamide

Oxytocin

Opiates

Desmopressin

Other causes include:

Carbamazepine

Oxcarbazepine

Cyclophosphamide

Ifosfamide

NSAIDs

MDMA

Hypovolemic

Hypovolemic hyponatremia can be due to renal salt loss (diuretic use, low aldosterone, acute tubular necrosis, or cerebral salt wasting) or extrarenal salt loss (diarrhea, vomiting or third-spacing).

Treatment

The treatment of hyponatremia involves fluid restriction and replacement of Na+ with hypertonic saline.

Caution must be exercised when treating hyponatremia. The sodium correction should not exceed 9 meq in 24 hours. In someone with symptomatic hyponatremia, it is allowable to raise the serum sodium level by 1 meq per hour the first few hours to a level of 120 meq/L.

Too rapid a correction of hyponatremia can result in osmotic demyelination syndrome (formerly called central pontine myelinolysis). Neuron damage from rapid osmotic shifts can result in paralysis, dysarthria, and dysphagia.

The treatment for euvolemic hyponatremia (asymptomatic) involves the use of fluid restriction, loop diuretics (to lower the urine osmolality), and/or salt tablets. The ADH receptor antagonist tolvaptan can also be used in cases of refractory hyponatremia.

Hypercalcemia

Hypercalcemia is defined as a total serum calcium > 10.3 mg/dL if albumin levels are normal, or an ionized calcium level > 5.2 mg/dL.

Causes

Hypercalcemia develops as a result of two factors: increased calcium ECF levels and a decrease in renal clearance of calcium.

Hypercalcemia may be the result of endocrinopathies, malignancies, granulomatous disease, and pharmacological side effects.

90% of cases of hypercalcemia are the result of primary hyperparathyroidism or malignancy.

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the primary cause of hypercalcemia among ambulatory patients. It is characterized by elevated serum Ca2+ and decreased serum PO4-. Causes include:

Benign adenoma of a parathyroid gland (85%)

Parathyroid hyperplasia (15%)

Parathyroid carcinoma (1%)

Malignancy is the most common cause of hypercalcemia among hospitalized patients. Hypercalcemia can result from osteoclast stimulation by tumor cells, PTHrP (PTH-related peptide) from tumor cells, and calcitriol produced by tumor cells.

The most common tumors that are associated with hypercalcemia are:

Breast cancer

Multiple myeloma

Lymphoma

Squamous cell carcinomas of the lung, head, & neck

Paget: increased cell turn over

Hypercalcemia secondary to hypervitaminosis D can result from exogenous vitamin D exposure or increased production of calcitriol in diseases with chronic granulomatous inflammation (e.g. tuberculosis and sarcoidosis) and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Pharmacological causes of hypercalcemia include:

Milk-alkali syndrome is the acute onset of hypercalcemia, alkalosis, and renal failure that results from consuming large amounts of antacids that contain calcium.

Vitamin D intoxication

Thiazide diuretics (inhibit renal excretion)

Lithium (may increase PTH levels)

Other rare causes of hypercalcemia include adrenal insufficiency, Paget’s disease (osteoclastic bone reabsorption), familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia and hyperthyroidism.

Symptoms

While hypercalcemia is defined as serum calcium > 10.3 mg/dL, symptoms generally do not appear until levels are >12 mg/dL. Even then, primary hyperparathyroidism is often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally.

Hypercalcemia-induced renal disease manifests with polyuria and nephrolithiasis.

Gastrointestinal symptoms of hypercalcemia include constipation, anorexia, vomiting, and occasionally signs of pancreatitis.

Hypercalcemia can cause neurologic symptoms of weakness, fatigue, confusion, stupor, and even coma.

If hypercalcemia is the result of increased osteoclast activity, it can result in osteopenia, fractures, and if severe enough osteitis fibrosa cystica. In long bones, osteitis fibrosa cystica results in “brown tumors”, which represents a mixture of fibrous tissue and poorly mineralized bone. The brown color comes from hemosiderin deposition.

EKG findings in hypercalcemia include shortened QT interval, and if severe enough, AV block.

Mnemonic:

Stones (nephrolithiasis)

Bones (bone aches and pains d/t osteitis fibrosa cystica)

Moans/groans (muscle pain, constipation, peptic ulcer disease)

Psychiatric overtones (depression, fatigue, anorexia, sleep disturbances, lethargy)

Diagnosis

Since calcium levels are influenced by albumin levels, ionized calcium or a corrected calcium should be measured. This is because only the ionized calcium is metabolically active.

The serum calcium concentrations decrease by 0.8 mg/dL for every 1.0 g/dL decrease in serum albumin concentration. As such, the equation for finding a corrected (aka adjusted) calcium concentration is:

Corrected [Ca2+] = Measured total [Ca2+] + {0.8 X (4.0 – [Albumin])}

Corrected [Ca2+] is the corrected serum concentration of total calcium

Measure total [Ca2+] is the measured serum concentration of total calcium

4.0 is the normal value of serum albumin concentration

[Albumin] is the measured serum albumin concentration

Most often, a diagnosis of hypercalcemia can be made by a thorough history and physical with minimal laboratory testing.

To determine the etiology of hypercalcemia, first, serum PTH levels must be measured.

Elevated levels of calcium should result in feedback inhibition of PTH. Hypercalcemia with elevated PTH suggests primary hyperparathyroidism or (less frequently) tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

If serum calcium is elevated and PTH is LOW, PTHrP is measured to look for possible malignant causes of the hypercalcemia.

If a patient is hypercalcemic with normal PTH and PTHrP levels, vitamin D levels are investigated. Elevated vitamin D and normal PTH/PTHrP is seen in:

Granulomatous disorders

Exogenous vitamin D overdose

Acromegaly

Patients with familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia may have normal or slightly elevated PTH, making this condition difficult to distinguish from primary hyperparathyroidism. The main distinguishing feature of this condition is the low urine calcium excretion(as opposed to the normal or high calcium excretion seen in primary hyperparathyroidism).

Serum phosphorus levels are also helpful in identifying the etiology of hypercalcemia:

Primary hyperparathyroidism: decreased phosphorus levels

Excess vitamin D: increased phosphorus levels

Treatment

Correction of hypercalcemia is based on severity, as indicated by the serum calcium level.

Mild hypercalcemia < 12 mg/dL

Moderate hypercalcemia 12-14 mg/dL

Severe hypercalcemia >14 mg/dL

Correction of hypercalcemia should begin with correction of hypovolemia with 0.9% saline and maintenance of adequate hydration. Hypovolemia prevents normal calciuresis, so correcting volume depletion will increase renal calcium excretion.

Fluid administration is the most important step in treating hypercalcemia.

In the event of moderate hypercalcemia, bisphosphonates (e.g. alendronate, zoledronic acid, pamidronate) may be used in addition to normal saline. Bisphosphonates are particularly effective in treating hypercalcemia from increased bone reabsorption.

Bisphosphonates bind to hydroxyapatite in bone, thereby inhibiting osteoclastic bone resorption.

Bisphosphonates (e.g. zoledronic acid, pamidronate) are the preferred agents for the treatment of hypercalcemia secondary to bone metastases. These agents inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption, thereby reducing the risk of pathologic fractures.

Calcitonin may be used in addition to saline and bisphosphonate therapy should serum calcium levels rise above 14 mg/dL. Calcitonin is antagonistic to the action of PTH and can decrease bone resorption of calcium. One benefit of calcitonin is that it is safe in renal failure.

Loop diuretics can be used in patients with renal or heart failure, at risk for volume overload. Loops lose calcium (vs. thiazide diuretics that increase calcium retention).

Glucocorticoids can decrease serum calcium levels in patients who are hypercalcemic due to granulomatous diseases (e.g. sarcoidosis) and some lymphomas.

Gallium nitrate inhibits bone resorption with the same efficacy of bisphosphonates, but it is nephrotoxic and contraindicated if creatinine is > 2.5 mg/dL.

Hypocalcemia

Hypocalcemia is defined as a total serum calcium concentration < 8.4 mg/dL or ionized calcium concentration < 4.2 mg/dL.

Hypoparathyroidism (most common cause) can result from:

Autoimmune disease

Malignant or infectious infiltrate

Iatrogenic (thyroidectomy)

DiGeorge syndrome

PTH release is impaired in hypomagnesemia (< 1mg/dL) as well as severe hyper magnesemia (> 6 mg/dL).

Except in cases of severe deficiency, vitamin D deficiency does not normally result in hypocalcemia because the secondary hyperparathyroidism is usually sufficient to correct calcium levels. Severe vitamin D deficiency is seen in:

Renal failure (decreased 1-α-hydroxylase activity)

Nephrotic syndromes

Advanced liver disease (decreased synthesis of vitamin D precursors)

Elderly with limited sun exposure

Significantly elevated serum phosphorus can result in hypocalcemia because phosphorus binds and precipitates calcium in the tissue. This can happen in renal failure, rhabdomyolysis, and exogenous phosphate administration.

Hypocalcemia also results from certain drugs which bind calcium:

Citrate (in transfused blood)

Foscarnet

Fluoroquinolones

Patients with hepatic or renal failure are at greatest risk for transfusion-related hypocalcemia since the liver and kidney normally metabolize citrate.

Recall that citrate is used to inhibit coagulation in blood products and chelates free calcium.

Alkalosis can result in hypocalcemia because alkalosis results in an increase in the number of negatively charged sites on albumin, which then bind calcium.

Pseudohypocalcemia is when total calcium is reduced due to decreased albumin but ionized (and hence metabolically active) calcium is normal.

See Fluid and Electrolytes: Hypercalcemia for information on correcting calcium based on abnormal albumin levels.

Hypocalcemia with low or inappropriately normal PTH levels suggests hypoparathyroidism.

Hypocalcemia with elevated PTH is seen in:

Renal failure

Vitamin D deficiency

PTH resistance

Hypocalcemia with low serum phosphorus suggests vitamin D deficiency, while hypocalcemia with high serum phosphorus suggests renal failure or intravascular chelation of calcium.

Both hypomagnesemia and hypermagnesemia can cause refractory hypocalcemia by inducing PTH resistance and/or decreasing PTH secretion. Hypocalcemia in these patients requires both magnesium and calcium repletion; it will not respond to calcium alone.

Symptoms

Moderate hypocalcemia results in increased excitability of muscles and nerves, which can lead to peri-oral tingling, parasthesias and tetany (Chvostek's and Trousseau's signs).

Severe hypocalcemia can cause laryngospasm, confusion, tetany, seizures, bradycardia and decompensated heart failure.

Clinical signs helpful in the evaluation of hypocalcemia include:

Trousseau sign is when carpal spasms develop if a blood pressure cuff is inflated above systolic pressure over the upper arm for 3 minutes. A positive Trousseau sign is indicative of hypocalcemia.

Chvostek sign is the twitching of facial muscles when the facial nerve is tapped anterior to the ear. It is a sign of hypocalcemia.

EKG findings in hypocalcemia include a prolonged QT interval as well as bradycardia.

Calcium supplementation is reserved as a treatment for severe hypocalcemia (symptomatic or with total serum calcium < 7.5mg/dL), and is given as Ca-gluconate (preferred) or CaCl. If severe enough, elemental calcium can be given as a bolus followed by Ca-gluconate.

Chronic hypocalcemia requires vitamin D supplementation.

If a patient is hypocalcemic with severe hyperphosphatemia, giving calcium can increase the precipitation of calcium-phosphorus in tissues. Dialysis may be preferred to first lower the phosphorus levels.

If a patient is hypocalcemic and hypomagmesemic, correct the hypomagnesemia before offering other treatments, or those treatments will be less effective.

Hyperkalemia

Hyperkalemia is defined as a serum K+ > 5.0 mEq/L.

Pseudohyperkalemia is a transient, clinically insignificant elevation in K+ levels immediately prior to sampling. Potential causes of pseudohyperkalemia include:

Hemolysis

Leukocytosis

Repeated fist clenching

Causes of a transcellular shift leading to hyperkalemia include:

Insulin deficiency

Acidosis

Massive cell destruction (tumor lysis syndrome)

Medications (see below)

Medications that are notorious for increasing potassium include:

β-blockers

Digitalis

Succinylcholine

ACEIs and ARBs

Potassium-sparing diuretics

NSAIDs

Trimethoprim

Symptoms

The most serious symptoms of hyperkalemia are the result of changes to cardiac muscle excitability.

Patients can present with palpitations, syncope, and sudden cardiac death.

Hyperkalemia can also affect the excitability of skeletal muscles, leading to weakness and flaccid paralysis. Hypoventilation can occur if muscles involved in respiration are affected.

Diagnosis depends on the following:

Thorough H&P (including drugs and disease that impair aldosterone)

Urine K+ excretion

Plasma renin activity, serum aldosterone, and serum cortisol (to evaluate renin-angiotensin-aldosterone pathway)

EKG

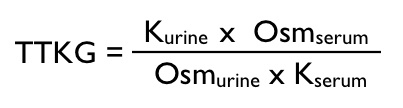

A TTKG > 10 in a patient with hyperkalemia is suggestive of an appropriate increase in the renal excretion of potassium. Use the trans-tubular potassium gradient, or TTKG, (described in hypokalemia) to evaluate renal K+ excretion.

A TTKG < 7 in a patient with hyperkalemia is suggestive of a deficiency of aldosterone, or decreased response to aldosterone. The kidney is unable to appropriately secrete the excess potassium. Use the trans-tubular potassium gradient, or TTKG, (described in hypokalemia) to evaluate renal K+ excretion.

EKG changes associated with hyperkalemia:

Increased T-wave amplitude or "peaked" T-waves (first findings)

Prolonged PR interval and Loss of P Waves

Prolonged QRS duration and "Sine-wave" pattern (late findings)

Treatment

When potassium levels are >7mEq/L OR there are changes consistent with hyperkalemia on ECG, medication should be used to rapidly correct potassium levels:

Insulin + Glucose

β2-agonists (e.g. albuterol)*

Bicarbonate*

*Should not be used as stand-alone therapies and are used best in combination with insulin and glucose.

The problem with medications to rapidly correct serum potassium (insulin + Glucose, β2-agonists, bicarbonate) is that they work by driving extracellular potassium intracellularly and do NOT decrease total body potassium but do allow time until such therapies can be initiated (dialysis, kayexalate).

Calcium gluconate is given to stabilize membrane excitability but does NOT decrease potassium levels. It is cardio-protective and is essential in protecting patients from fatal arrhythmias. It is used best in conjunction with other therapies (insulin + glucose) that drive potassium intracellularly. First step in trauma patients with high K levels.

Several therapies can be used to remove excess potassium from the body in patients with persistently elevated potassium or in patients with acute hyperkalemia along with rapid acting agents:

Loop or thiazide diuretics

Cation exchange resins (Kayexalate)

Dialysis: use for intractable hyperkalemia or renal failure

Sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) is a cation exchange resin that works by increasing GI excretion of potassium.

The most appropriate treatment for patients with moderate levels of hyperkalemia (< 6.5meq) without ECG changes is loop or thiazide diuretics + normal saline and removal of potentially reversible causes (eg. discontinuing ACEi). This can be used in patients with ESRD or chronic kidney disease who may have elevations in potassium due to poor excretion or concomitant use of ACEi/ARBs.

Sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) is the preferred treatment in patients with severe hyperkalemia with EKG changes where dialysis is not readily available. Although commonly used in clinical practice, Kayexelate use carries with it a small but potentially fatal side effect of intestinal necrosis. It is strongly contraindicated in post-operative patients.

Hypokalemia

Hypokalemia is defined as a serum K+ concentration less than 3.5 mEq/L.

Hypokalemia can result from decreased K+ intake, a transcellular shift, renal K+ loss, and non-renal K+ loss.

A transcellular shift of K+ can occur as a result of insulin, alkalemia, and activation of β2 receptors.

Alkalemia can lead to hypokalemia since H+ is pushed out of cells to correct the alkalemia, and in exchange K+ is pushed inside cells.

Insulin activates the Na+/K+-ATPase, which pushes K+ into cells.

β2 receptors also push K+ into cells.

Most cases of K+ loss are renal in nature.

Increased urine flow increases K+ loss, leading to hypokalemia. It can be seen with diuretic use, osmotic diuresis (glucosuria, hyperuremia), and inherited disorders such as Bartter and Gitelman syndromes.

Since aldosterone promotes renal K+ excretion, mineralocorticoid excess can lead to hypokalemia.

Cortisol has weak mineralocorticoid properties. Cushing’s syndrome can lead to hypokalemia.

Renal tubular acidosis type 1 and type 2 result in hypokalemia (type 4 results in hyperkalemia).

GI loss of potassium may be seen in the following conditions:

Diarrhea (worsened by laxatives or enemas)

Vomiting

Disorders of the colon in which potassium cannot be absorbed

Symptoms

There are a variety of presenting symptoms of hypokalemia. In general, hypokalemia has the most pronounced clinical impact on the muscles (including the heart).

Common symptoms of a less severe hypokalemia include fatigue, myalgias, muscular weakness, and cramps. Smooth muscle can also be affected, leading to constipation.

Severe hypokalemia can result in paralysis, hypoventilation, rhabdomyolysis and cardiac abnormalities: flat T waves, U waves, and QT prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, and eventually cardiac arrest.

Diagnosis

Urine K+ and acid-base status are critical in identifying the etiology of hypokalemia.

Since K+ is readily absorbed into cells, spurious hypokalemia results when a large number of metabolically active cells in a sample absorb the extracellular K+. It is not a true hypokalemia with clinical symptoms.

In hypokalemia, the kidneys should respond by secreting < 25 mEq/day.

TTKG (transtubular potassium gradient) is calculated as follows: TTKG = (urine K/serum K)/(urine osmolality/serum osmolality)

TTKG <2 is suggestive of a non-renal source of the hypokalemia.

TTKG >4 suggests that the hypokalemia is the result of inappropriate renal secretion of K+.

After determination of urine K+, an arterial blood gas should be performed to check acid-base status.

Hypokalemia is normally associated with metabolic alkalosis. Exceptions in which metabolic acidosis is associated with hypokalemia include lower GI loss, DKA, and renal tubular acidosis types 1 and 2.

Treatment

Treatment involves treating the underlying etiology and replacing potassium. K+ replacement can be either oral or IV.

Oral is preferred, with 40 mEq given as often as every 4 hours.

For every 10mEq of KCl given, serum K+ should increase by 0.1mEq/L.

K+ should be given in a saline solution and not with dextrose because the dextrose can lead to insulin secretion, driving K+ into the cells and potentially worsening the hypokalemia.

If the patient is suffering from severe and life-threatening hypokalemia, use IV KCl at a max of 20 mEq/hr (central line).

Hypomagnesemia is common in hypokalemia. Treating the hypomagnesemia allows effective K+ replacement.

Hematuria

Hematuria results when whole red blood cells leak into the urine somewhere in the genitourinary tract.

Glomerular hematuria

Nonglomerular hematuria

Type of hematuria

Microscopic > gross

Gross > microscopic

Common etiologies

Glomerulonephritis <br / > Poststreptococcal IgA nephropathy Basement membrane disorder Alport syndrome

NephrolithiasisCancer (eg, renal, prostate)Polycystic kidney diseaseInfection (eg, cystitis)Papillary necrosis

Clinical presentation

Nonspecific or no symptomsNephritic syndrome

DysuriaUrinary obstruction

Urinalysis

Blood & proteinRBC casts, dysmorphic RBCs

Blood but no proteinNormal-appearing RBCs

Causes of hematuria can include malignancy (bladder and renal cell carcinoma), infection, stones, glomerulonephritis, vasculitis, and trauma.

Gross (ie, visible or macroscopic) hematuria can be classified based on the stage of voiding at which bleeding predominates:

Initial hematuria is characterized by blood at the beginning of the voiding cycle.

Total hematuria is characterized by blood during the entire voiding cycle.

Terminal hematuria is characterized by blood at the end of voiding cycle.

Initial hematuria suggests urethral damage (urethritis, foley catheter injury), terminal hematuria indicates bladder or prostatic damage, and total hematuria reflects damage in the kidney or ureters.

Terminal hematuria often suggests bleeding from the prostate, bladder neck or trigone, or posterior urethra. In this patient, the presence of terminal hematuria with clots suggests bleeding within the bladder or ureters and is concerning for urothelial cancer, particularly given his risk factors of age (>40), sex, and smoking. He should be evaluated for bladder cancer by cystoscopy.

Glomerular diseases can cause nephritic syndrome with microscopic or gross hematuria. Patients can also present with total hematuria. However, clots would be unusual, and urinalysis frequently shows red blood cell casts and may show proteinuria.

Hematuria is divided into gross and microscopic forms.

Gross hematuria refers to urine that contains so many red blood cells that it is visibly pink, red, or brown.

Patients may also have what appears to be gross hematuria (visibly red, pink or brown urine) but a dipstick negative for blood. This occurs when other substances (such as the red pigment in beets) turn the urine red. This is harmless, and does not require follow-up.

Microscopic hematuria refers to urine with ≥3 red blood cells per high powered field on microscopy, but normal gross coloration (i.e. the urine appears yellow or clear to the naked eye).

Symptoms

Depending on the cause of the hematuria, various other symptoms may be present.

Kidney stones can present with acute flank pain only or flank pain with radiation to the ipsilateral inguinal area. Pain is due to stone migration along the kidney and ureter.

Renal infarction can also present with acute flank pain and gross or microscopic hematuria.

Bladder cancer and renal cell cancer often present with painless hematuria (macroscopic or microscopic)

Cystitis often presents with dysuria, urinary frequency, and urinary urgency. If cystitis progresses to pyelonephritis, you may see fever and flank pain.

Diagnosis

Lab studies can help identify the cause of hematuria, as well as differentiate true hematuria from false positive urine dipstick results.

Remember that a urine dipstick detects heme, NOT whole red cells. A dipstick cannot distinguish hematuria (red blood cells in the urine) from hemoglobinuria (hemoglobin in the urine, as is seen in hemolysis) or myoglobinura (as is seen in rhabdomyolysis). A dipstick positive for “blood” must ALWAYS be followed up with urine microscopy to detect red blood cells.

All causes of true hematuria will show >3 red blood cells per high powered field on urine microscopy.

Urine cytology may be used to look for signs of malignancy and is indicated in patients at increased risk for urothelial cancers, such as smokers and patients with certain chemical exposures. Patients with positive cytology should be referred to a urologist for further workup, including cystoscopy.

Hemolysis causes hemoglobinuria (false positive dipstick for blood) as well as elevated serum LDH and indirect bilirubin.

There are other lab anomalies associated with hemolysis, but these are the ones you will most commonly use on the wards!

Rhabdomyolysis causes myoglobinuria (false positive dipstick for blood), with an elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level. Hyperkalemia (as K+ is released from muscle cells), hyperuricemia (from cellular turnover) and renal failure (from myoglobin buildup in the kidneys) may be present.

Radiologic studies for evaluating hematuria include X-rays, ultrasound, and CT scan.

Abdominal X-ray is useful for following a kidney stone over time, as most kidney stones are calcium-based and radiopaque. However, it is important to remember that uric acid stones are radiolucent, so a negative abdominal plain film does not definitively rule out kidney stones! Note: This is where the abdominal plain film got the nickname “KUB” – it shows the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, and can thus be used to detect and follow stones as they pass through the system.

Renal ultrasound can help differentiate cystic vs solid renal masses. Ultrasound can be used to look for stones, but only the kidneys and the proximal ureter can be visualized, making non-contrast abdominal CT the imaging modality of choice for patients with suspected stones.

CT scan of the abdomen with contrast is used to detect and stage renal malignancies.

Diagnostic interventional studies are often needed in order to obtain a final diagnosis. This may include cystoscopy to evaluate for bladder cancer, retrograde pyelogram for ureteral malignancy, and kidney biopsy for glomerulonephritis or renal vasculitis.

Treatment

Hematuria is rarely dangerous in itself. The treatment of hematuria centers around finding and treating the underlying cause.

Intravascular hemolysis: Look for the underlying cause. The differential is wide and includes hereditary spherocytosis, sickle cell disease, and many others. In the meantime, start intravenous saline to preserve kidney function and correct electrolyte abnormalities (eg, hyperkalemia) if present.

Rhabdomyolysis: Start IV normal saline to help preserve kidney function, and correct electrolyte abnormalities.Rhabdomyolysis usually resolves on its own, so care is supportive.

Cystitis, pyelonephritis, prostatitis: Urine culture and antibiotics are usually appropriate.

Kidney Stones

The most common kidney stone is a calcium stone (specifically, oxalate). The stones consist of either calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate. Calcium stones often appear envelope-shaped.

A struvite stone is composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate. These stones occur when a patient develops an upper urinary tract infection with a urease-producing organism such as Klebsiella or Proteus. Struvite stones have a coffin-lid appearance.

Urease breaks down urea to ammonia and carbon dioxide

Urea → 2NH3 + CO2

The ammonia then combines with water

NH3 + H20 → NH4+ + OH-

The result of ammonium in an alkaline urine increases the chance of struvite stone development.

Uric acid stones may be found in patients with gout, diabetes mellitus, chronic diarrhea, and increased uric-acid production. These stones have a pleomorphic shape and sometimes appear diamond-shaped.

Patients with cystinuria have an impaired renal cystine transport. There is decreased proximal tubular reabsorption of cystine which causes urinary cystine excretion and stones. They are hexagonal in shape.

Signs and symptoms of renal stones include renal colic, ± hydronephrosis, ± infection, ± gross hematuria.

Diagnosis

Abdominal x-ray will show most stones, except for very small stones, and uric acid stones which are radiolucent.

Uric acid stones are radiolUcent.

Urinary pH can help in the diagnosis of nephrolithiasis and the specific type of stone.

pH > 6, likely struvite stones

pH < 5, likely uric acid stones

Noncontrast abdominal/pelvic CT is fast, requires no IV contrast and is most useful to diagnose small stones (95% sensitivity), hydronephrosis, hydroureter, and perinephric stranding.

Intravenous pyelogram (IVP): clearly outlines the entire urinary system, making it easy to see hydronephrosis and the presence of any type of stones. An intravenous pyelogram (IVP) uses IV contrast and plain x-ray to visualize the urinary system. IVP was previously the test of choice for diagnosing urinary stones. However, due to the risk of contrast administration (eg, allergy, acute kidney injury), noncontrast CT is now preferred.

A renal ultrasound can only show the kidney and proximal aspect of the ureter. Stones are visualized as bright echogenic foci with posterior shadowing. Ultrasound is also useful for visualizing hydronephrosis. It is not good for visualizing the lower urinary tract.

Treatment

Patients with nephrolithiasis are most commonly treated with analgesics and hydration until the stone passes.

Small (5mm or less) stones have a 90% chance of passing spontaneously and can be handled with analgesia (NSAIDs or opiates if necessary) and IV or PO hydration.

Passage of small stones may also be facilitated by use of alpha-blocking medications, such as tamsulosin. Tamsulosin is an alpha 1 antagonist that relaxes ureteral muscle and decreases intraureteral pressure. This facilitates stone passage and reduces the need for analgesics.

Large (8mm or more) stones will only have a 5% chance of spontaneous passage and intervention is often required with either extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy or percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

The most common tool for the larger stones is extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) but this cannot be used in pregnancy, bleeding diathesis, or extremely large stones.

Potassium citrate may be used to treat uric acid stones by alkalization of the urine. Allopurinol can be added if there are recurrent symptoms despite initial measures, especially if hyperuricosuria or hyperuricemia occurs.

Increased sodium intake enhances calcium excretion (hypercalciuria), and low sodium intake promotes sodium and calcium reabsorption through its effect on the medullary concentration gradient. Reabsorption of sodium and calcium is coupled via complex mechanisms involving the calcium-sensing receptor in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. Therefore, patients with recurrent renal calculi should be advised to restrict sodium intake.

Last updated