10 Ortho

Autoimmune arthritis

Reactive Arthritis

Reactive arthritis, formerly called Reiter’s syndrome, is an asymmetric arthropathy with nongonococcal urethritis/cervicitis, dysentery, inflammatory eye disease, or mucocutaneous disease. It is also known as a seronegative spondyloarthropathy.

75% of patients are HLA-B27 positive.

Patients are typically between ages sixteen and thirty-five.

Forty-percent of patients will have a current or recent Chlamydia infection.

Other related bacteria include

Shigella

Salmonella

Yersinia

Campylobacter

Mycoplasma

Symptoms

The clinical features of reactive arthritis vary, but the classic triad is the same as Reiter’s syndrome (urethritis, conjunctivitis/iritis, and arthritis). The classic triad can be remembered using the mnemonic “can’t pee, can’t see, can’t climb a tree.”

Patients will have an enteric or urogenital infection one to four weeks before symptoms.

Patients have painful joints with effusions and limited mobility. New joints may become painful sequentially over days (asymmetric arthritis). The joint pain can be continuous or wax and wane over a long-term.

Fatigue, malaise, weight loss, and fever are common in reactive arthritis.

There are often lesions of the skin (keratoderma blennorrhagicum) and gastrointenstinal tract (resembling irritable bowel syndrome).

Diagnosis

Reactive arthritis diagnosis couples clinical features with synovial fluid that lacks infection or crystals.

Laboratory findings include an elevated serum CRP and ESR.

Rule out other seronegative spondyloarthropathies, infectious arthritis, crystal-induced arthritis (e.g. gout, pseudogout), rheumatic fever, and gonorrhea.

Test urethral specimens for Chlamydia and gonorrhea since 40% of patients will have a recent or current infection.

Culture synovial fluid for gonococci and other pathogens to rule out infective arthritis.

Treatment

Treat reactive arthritis with rest, joint immobilization, and NSAIDs, and antibiotics if there is a concurrent genitourinary infection.

If NSAIDs fail to relieve symptoms, try sulfasalazine and immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine.

Antibiotics used for a concurrent genitourinary infection include ceftriaxone and doxycycline or azithromycin for coverage of Chlamydia and Gonorrhoea.

Reactive arthritis complications are rare but still exist. Some patients may develop chronic uveitis that ultimately causes visual impairment.

Cardiac complications are rare but include:

Aortitis

Aortic regurgitation

Heart block and arrhythmias

Mitral regurgitation

Some cases of serum A amyloidosis have been reported. These patients typically have proteinuria or nephrotic syndrome.

Patients may develop chronic prostatitis or other complications associated with high-risk sexual behavior. HIV patients develop polyarticular arthritis, disabling enteritis, and extensive cutaneous manifestations.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic systemic autoimmune disorder that causes inflammation of synovial joints, which leads to joint erosion.

Rheumatoid factor is an IgM against the Fc portion of the patient’s own IgG antibodies.

Rheumatoid factor binds to circulating IgG to form immune complexes, which deposit in synovial joints. The complexes trigger a cell-mediated inflammatory response, which leads to the formation of a pannus (granulation tissue) on the articular cartilage.

IL-1 and TNF-alpha, released by mononuclear cells in the pannus, are responsible for initiating the joint damage seen in rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis affects 3% of women and 1% of men.

People who carry the HLA-DR4 allele are predisposed to developing rheumatoid arthritis.

Symptoms

Rheumatoid arthritis typically presents with morning stiffness and usually affects the hands and feet first.

Rheumatoid arthritis affects the PIP and MCP joints whereas osteoarthritis affects the PIP and DIP joints. The DIP joints are usually spared in rheumatoid arthritis.

Classic deformities present in rheumatoid arthritis include:

Ulnar deviation of the fingers at the MCP joint

Swan-neck deformities, which is a hyperextended PIP joint and flexed DIP

Boutonniere deformities, which is a flexed PIP and extended DIP

Z-thumb, which is extension of the IP joint and with flexion and subluxation of the MCP joint

MCP joint hypertrophy

Patients with cervical spine involvement often complain of neck pain, stiffness, and radicular pain in the upper extremity. Subluxation with spinal cord compression can present with hyperreflexia or upgoing toes on Babinski testing.

Rheumatoid arthritis is also associated with systemic manifestations, which include:

Pericarditis

Scleritis

Felty’s syndrome (RA with splenomegaly and neutropenia)

Still’s disease (RA with fever, rash, and splenomegaly)

Interstitial lung disease

Caplan syndrome (RA plus pneumoconiosis)

Sjogren’s syndrome, which is an autoimmune destruction of salivary and lacrimal glands.

Diagnosis

Joint fluid aspiration in rheumatoid arthritis shows decreased complement and an increased leukocyte count.

Additional lab findings in rheumatoid arthritis include:

Increased ESR and CRP

Positive rheumatoid factor (RF) titer in 75-80% of patients

Positive ANA in up to 40% of patients

Anti-CCP antibodies (cyclic citrullinated peptides) (similar sensitivity to RF but higher specificity ~90%)

X-ray imaging is usually the first choice in working-up rheumatoid arthritis, which can show joint erosion, joint space narrowing, and subluxation. Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings.

Treatment

Methotrexate is the initial disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) of choice for most patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Other non-biologic DMARDs that can be used as first-line agents for patients with rheumatoid arthritis include:

Sulfasalazine

Hydroxychloroquine

If patients have symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis that persist for greater than 6 month the next step is to either:

Add biologic DMARD such as etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab which are TNF-alpha inhibitors

Add additional non-biologic agent such as leflunomide, sulfasalazine or hydroxychloroquine.

All patients should be screened for hepatitis B and C and latent tuberculosis prior to beginning therapy with DMARD (both biologic and non-biologic).

NSAIDs and glucocorticoids are only used as adjunctive antiinflammatory agents in patients who are initially presenting with RA who are being started on a DMARD regimen or patients with disease flare ups while on a DMARD regimen. They DO NOT prevent joint disease nor are they indicated for long term therapy of rheumatoid arthritis.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is an autoimmune disease that affects the spine and pelvis, which ultimately results in fusion of the affected bones.

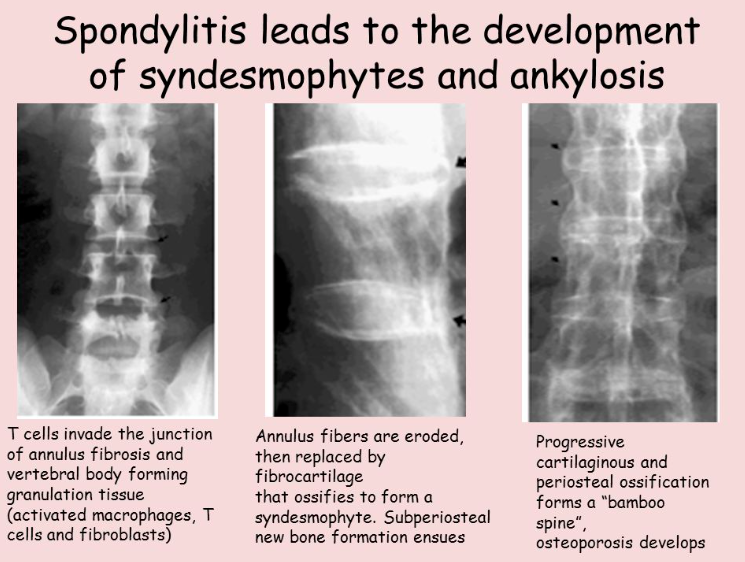

The chronic inflammation of the joints leads to erosion, soft tissue ossification, and joint ankylosis. This is often seen over intervertebral discs leading to syndesmophyte formation, which are bridging osteophytes.

Ankylosing spondylitis is associated with systemic manifestations including:

Anterior uveitis

Renal amyloidosis

Pulmonary fibrosis

Aortitis

Cardiac conduction abnormalities

Ankylosing spondylitis is most common in the 20-40 year age group with Caucasian males being most frequently affected.

Symptoms

Symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis include:

Inflammatory lower back pain

Neck and upper thoracic pain

Pain down the posterior lower extremity from sciatic nerve compression

Shortness of breath from costovertebral joint involvement

Enthesitis: Achilles tendon

The inflammatory back pain of ankylosing spondylitis usually has at least 4 of the following 5 characteristics:

Onset before 40 years old

Gradual onset

Relieved with exercise

No improvement with rest

Night pain relieved upon arising

Physical exam findings in ankylosing spondylitis include:

Limited range of motion in the chest, hip, or spine

A painful kyphotic spine

Hip flexion contracture

Roughly 90% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis are positive for HLA-B27.

Diagnosis

X-ray images of ankylosing spondylitis show characteristic “bamboo spine,” which is the fusion of several vertebrae. Because MRI can detect inflammation, it can be used to detect ankylosing spondylitis in younger patients.

Treatment

Nonoperative treatment of ankylosing spondylitis includes physical therapy and NSAIDs, with exercises to help slow the onset of permanent deformities in the spine. Later in the disease course, sulfasalazine, methotrexate, and/or anti-TNF drugs may be required.

Operative treatment of ankylosing spondylitis involves spinal decompression with instrumented fusion if significant neurological problems are present.

Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is a chronic functional illness characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, often accompanied by fatigue, sleep trouble, cognitive dysfunction, and depressed mood/episodes.

Fibromyalgia typically affects females aged twenty to sixty years.

The cause is unknown, but appears related to physical activity, anxiety, and stress.

Physical examination of a patient with fibromyalgia reveals tenderness in multiple soft tissue locations.

Diagnosis

The manual tender-point survey (MTPS) is a standardized approach to assessing patients with suspected fibromyalgia; it consists of 9 symmetrically distributed pairs of tender-point sites as well as 3 control sites. Examples of tender-point sites include:

Mid-trapezius

Lateral epicondyle

Costochondral junction

Greater trochanter

Fibromyalgia diagnosis is a combination of the American College of Rheumatology’s 1990 and 2010 guidelines, but it should be suspected in patients with multifocal pain with no damage or inflammation in the affected areas. The general criteria are:

Widespread pain index (WPI) ≥ 7 and symptom severity (SS) scale score ≥ 5 or WPI 3-6 and SS scale score ≥ 9

Symptoms present at a similar level for at least three months

No other explaining disorder

Pain in at least 11 of 18 tender points on digital palpation (occiput, low cervical, trapezius, supraspinatus, second rib, elbow, gluteal, greater trochanter, knees)

ACR 2010 Guidelines and ACR 1990 Guidelines

Don’t confuse fibromyalgia with SLE, RA, ankylosing spondylitis, polymyalgia rheumatic, Sjogren syndrome, Lyme disease, idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, neurological disorders, and endocrine disorders. These conditions can occur in conjunction with fibromyalgia.

Rule out other causes of focal symptoms like irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular joint, interstitial cystitis, headaches, entrapment syndromes, and peripheral neuropathies.

You should check CBC, ESR, muscle enzymes, liver/thyroid function, which will be normal.

Fibromyalgia shares symptoms with other diseases, which complicates diagnosis.

Fibromyalgia has associations with systemic medical conditions, autoimmune disorders, and psychiatric disorders.

Fibromyalgia has a large overlap with functional somatic syndromes.

Treatment

The initial treatment approach for patients with fibromyalgia is conservative therapy that includes:

Patient education

Regular aerobic exercise

Proper sleep hygiene

Education is an important component of fibromyalgia treatment. Patients should be reassured that fibromyalgia is a benign condition with favorable prognosis. Furthermore, they should know it is chronic but non-progressive.

Tricyclic antidepressants (eg. amitriptyline) are used as first line treatment for patients with fibromyalgia who do not respond to conservative treatment alone.

Other medications besides TCAs can be used to treat fibromyalgia including:

Pregabalin

Duloxetine

Milnacipran

Polymyalgia rheumatica

Polymyalgia rheumatica is an autoimmune disease with several sites of muscle and joint pain and it is commonly associated with temporal arteritis.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is more common in:

Women

People of northern European descent (i.e., Scandinavian countries)

The elderly (peak incidence between 70 and 80 years old)

Symptoms

The presentation of polymyalgia rheumatica includes symmetrical morning muscle stiffness and pain in the neck, shoulders, and hips.

Physical exam findings include fatigue, edema of the extremities, tenderness to palpation, movement limited by pain, but normal muscle strength unlike polymyositis, which presents with decreased muscle strength.

Diagnosis

Laboratory findings in polymyalgia rheumatica include decreased hematocrit with increased ESR.

MRI of polymyalgia rheumatica is associated with increased signal at tendon sheaths and tissue outside of joints.

Because polymyalgia rheumatica has such a strong correlation with temporal arteritis, patients should automatically be worked up for it as well.

Treatment

Treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica involves low dose corticosteroids that are slowly tapered.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is an arthropathy associated with psoriasis that shares features of rheumatoid arthritis and seronegative spondyloarthropathies.The cause is unknown.

Less than 10% of psoriasis patients develop psoriatic arthritis.

Patients are typically 30-55 years old at onset.

Males and females are equally affected; however, their presentations differ (discussed later).

It may be initiated by interferon-gamma treatment for psoriasis.

Other causes include genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors.

Psoriatic arthritis typically develops after suffering psoriatic skin disease.

One-third will have acute onset, which may be associated with HIV.

Symptoms

Psoriatic arthritis is typically asymmetric and polyarticular. The symmetric form, when it occurs, is seen mostly in females; whereas, spinal involvement occurs mostly in men.

Upper extremities are most often involved; smaller joints are more common than larger joints. Involvement of the distal interphalangeal joint is common, resulting in “sausage” shaped fingers.

30% of patients will have eye inflammation (generally conjunctivitis, sometimes iritis, rarely uveitis).

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis relies on the CASPAR criteria, which are too specific for medical school rotations. Other diagnostic tests include blood tests and imaging.

Blood tests may show:

Mild anemia

Elevated ESR

Negative rheumatoid factor

Negative ANA

Increased uric acid

Imaging can help identify arthritic bone lesions.

HIV testing may be necessary if the symptoms were acute.

If you suspect oligoarticular/axial types, rule out:

Reactive arthritis

Ankylosing spondylitis

Enteropathic arthritis

Follow the link if you are interested in learning more about CASPAR criteria.

Consider rheumatoid arthritis in patients with symmetrical psoriatic arthritis.

Psoriatic arthritis is rarely disabling and has few complications.

There is an increased risk, shared with psoriasis, of hypertension.

Some patients may develop hallux valgus.

Treatment

Treat psoriatic arthritis with NSAIDS; however, if persistent, rheumatoid arthritis medications may be warranted.

Pregnancy improves symptoms in 80% of patients.

Surgery may be indicated in patients with intractable pain or lost joint function.

Bone

Lower back pain

Muscle Strain

Muscle strain is the most common etiology underlying a presenting complaint of lower back pain.

Patients complain of pain associated with and/or aggravated by activity, characterized by stiffness and difficulty bending the back. Pain is generally more localized and lacks radiating qualities.

Degenerative Disc

Degenerative disc disease causes lower back pain which is exacerbated by flexion of the spine and increases in intra-abdominal pressure. Some patients may experience radiculopathy, progressive worsening of sciatica and cauda equina syndrome (a surgical emergency).

A positive passive straight leg test raise is consistent with degenerative disc disease, and is typically negative in the setting of lumbar spinal stenosis.

Evaluation of the L4, L5 and S1 nerve roots revealing focal deficits is consistent with lumbar disc herniation, as lateral herniations of the L4/5 and L5/S1 discs account for ~95%.

Spinal Stenosis

Lumbar spinal stenosis typically causes lower back/leg pain relieved by sitting and flexion of the spine. Patients classically present with neurogenic claudication, which is characterized by leg or buttock pain that is induced by walking or standing and relieved by sitting. In contrast to vascular claudication, these symptoms can be elicited by standing without walking.

Unilateral radicular pain that is induced or exacerbated by lumbar extension (positive Kemp sign) is consistent with lumbar spinal stenosis.

Symptoms of neurogenic claudication due to spinal stenosis classically improve if patients walk while leaning over a shopping cart. This is due to increased spinal canal diameter with forward flexion of the spine.

Infectious

Infectious/metastatic etiologies should be considered when lower back pain is accompanied by otherwise unexplained systemic or constitutional findings (e.g. fevers of unknown origin, rapid unintentional weight loss) or in a patient with a history of malignancy or IV drug use.

Exam of patients with non-organic pain may reveal positive Waddell’s signs (superficial tenderness to palpation, discrepancy between seated and supine straight leg tests, overreaction during exam, etc.).

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for lower back pain is broad and includes the following:

Musculoskeletal injury

Degenerative disc disease

Lumbar spinal stenosis

Osteomyelitis

Malignancy

Degenerative arthropathy

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (don't forget this one!)

Non-organic etiology

Diagnostic imaging is necessary when the following red flags are present in a patient with lower back pain:

Trauma

Unexplained constitutional symptoms (e.g. fever, weight loss)

History of malignancy

History of IV drug use

Focal neurological deficits

Cauda equina syndrome

History of abdominal aortic aneurysm or pulsatile abdominal mass on exam

If none of these are present through the history and physical examination, then imaging is NOT indicated as part of the initial management.

Plain films may demonstrate fracture, degenerative spinal changes, spondylolisthesis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and evidence of infection or malignancy.

MRI has become the preferred modality for evaluating spinal pathophysiology, and may reveal disc herniation, spinal stenosis, osteomyelitis, discitis, spinal/epidural abscesses, and bony metastases.

CT can demonstrate bony abnormalities better than MRI, and can detect sacroiliac joint changes in the setting of ankylosing spondylitis before they are visible on plain film.

Bone scan is neither as sensitive nor as specific as MRI in the detection of spinal osteomyelitis or metastasis.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) with or without C-reactive protein (CRP) have high sensitivity for osteomyelitis and reasonable sensitivity for bony metastasis, but are poorly specific. In the setting of infection (osteomyelitis), the ESR and CRP may be elevated before the leukocyte count.

90% of lower back pain resolves within one year with conservative management.

If no red flags are present through the history or physical examination, then imaging is NOT indicated. The most appropriate first step is to manage the patient conservatively with NSAIDs, local heat, physical therapy, and continued activity (NOT bed rest!), with follow up in 4-6 weeks.

The most appropriate next step for patients who fail conservative management, who present with additional red flag symptoms, or who endorse radiculopathy/sciatica is to obtain AP & lateral plain films. Obtain an ESR if there is any concern for systemic illness. If both are negative, manage conservatively for 4-6 weeks.

The most appropriate next step is to obtain MRI/CT in the following situations:

Patients with unremarkable plainfilms and persistent symptoms

Patients with abnormal plain films

Patients with an elevated ESR

Patients who present with acutely progressive radiculopathies or focal neurological deficits

Patients with bladder dysfunction, saddle anesthesia, or cauda equina syndrome

Patients with acutely progressive radiculopathies or focal neurological deficits and concern for cauda equina syndrome deserve emergent neurosurgery or orthopedic spinal surgery consult.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a loss of osteoid (organic bone matrix) and mineralized bone, however the process of mineralization is normal. Therefore osteoporosis is a quantitative (not a qualitative) defect.

Decreased bone mass and decreased bone density manifest as:

Decreased thickness of cortical and trabecular (spongy) bone

Fewer trabecular interconnections

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines osteoporosis as a lumbar spine (L2-L4) density level 2.5 standard deviations below the peak bone mass of a 25-year-old individual. Milder cases of low bone density with a t-score between -1.0 and -2.5 indicates osteopenia and places the patient at risk of subsequently developing osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is the most common metabolic disorder of bone.

Osteoporosis is more common in women because of the following:

Women have lower peak bone mass

Tend to live longer than men

Rapid bone loss during menopause secondary to decreased estrogen production

Genetics play a greater role in the development of osteoporosis than daily activity or calcium intake.

Osteoporosis is most commonly seen in older Caucasian postmenopausal women, though it may also affect men and premenopausal women.

The pathogenesis of osteoporosis is multifactorial, but the essential steps involve decreased peak bone mass or relative predominance of bone resorption relative to mineralization.

Decreased peak bone mass is seen in cases of malnutrition such as eating disorders or malabsorptive diseases like celiac disease. Patients may fail to accumulate sufficient bone mass (a process which stops by the third decade of life) due to insufficient accumulation of calcium and/or vitamin D, predisposing them to osteoporosis.

Increased resorption relative to the production of new bone can be seen in a variety of disease states which ultimately predispose the patient to osteoporosis. Such states include:

Old age: After about 30-45 years of age there is a switch from net bone formation towards net resorption. This can eventually lead to osteoporotic bone. This shift is attributed to the decline in differentiation and activity of osteoblast cells.

Sex steroid deficiency; In pubertal development, sex hormones are essential for proper bone growth and mineralization. Abnormal hormone levels may lead to suboptimal bone mass. In adults (especially females) estrogen plays an essential role in prolonging the lifespan of osteoblasts and inhibiting osteoclast activity. Women who undergo early menopause are known to be at a higher risk for osteoporosis.

Decreased load bearing: Bone formation is favored by weight bearing exercises as physical stress stimulates osteoblastic activity. Sedentary lifestyles are associated with a higher risk of developing osteoporosis. Individuals with high BMIs have a lower risk of osteoporosis and fracture, likely due to increased mechanical loading. Similarly, lower BMIs are associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

Glucocorticoid use: Glucocorticoids inhibit the activity of osteoblasts and facilitate bone resorption by increasing osteoclastic activity leading to increased bone turnover.

Diet and lifestyle factors such as alcohol and smoking are associated with decreased peak bone mass accumulation and further increase the risk of osteoporosis through a variety of mechanisms. Either substance can increase free radical production, upset hormonal balance or impair healing. The details of this process are poorly understood.

Osteoporosis is largely asymptomatic and does not present clinically until a fracture has occurred and the patient notes pain or deformity at the fracture site.

The most common fractures seen in osteoporosis are vertebral fractures,which may present with acute changes in height and/or back pain.

Hip fractures are the second most common type of fracture seen in osteoporosis and are likely to occur at the femoral head. The classic presentation of a hip fracture involves a history of a fall, hip pain (which may also involve the knee), deformity, and an inability to bear weight on the affected extremity. Most fractures occur as a result of the fall, but in some cases there is an initial fracture then the fall.

In non-osteoporotic individuals, a simple fall should NOT produce fractures. A fracture that occurs in the setting of a brittle bone with minimal trauma is referred to as a pathological fracture.

Radius fractures, also known as Colles fracture, can also occur, especially immediately after menopause.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by DEXA scan or by the occurrence of characteristic fractures (vertebral or hip) given consistent history, physical and lab findings.

Lab tests can be used to exclude secondary conditions that can undermine bone density such as:

Hyperthyroidism

Hypothyroidism

Hypercortisolism

Hyperparathyroidism

Renal or hepatic dysfunction

A DEXA scan is indicated as a screening tool for osteoporosis in all women over the age of 65.

Treatment

Treatment of osteoporosis consists of lifestyle adjustment; vitamin D and calcium supplementation; and pharmacologic management with bisphosphonates.

Lifestyle adjustments that may delay progression of osteoporosis include; engaging in weight bearing exercise, smoking cessation, limiting alcohol intake, and improving diet to include sources of calcium and vitamin D.

All patients with osteoporosis or osteopenia (T-score between -1 and -2.5) should be started on vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent any deficiencies that may accelerate bone loss.

Bisphosphonates, preferably alendronate or risedronate, may be used to slow down bone turnover and have been shown to reduce the risk of hip and vertebral fractures in patients with osteoporosis.

Raloxifene should be reserved for patients with osteoporosis who cannot tolerate bisphosphonate therapy. Raloxifene is a selective estrogen receptor agonist that inhibits bone turnover. Raloxifene acts as a selective agonist of the estrogen receptor and has similar effects as estrogen on bone metabolism. However, it acts as an antagonist to the estrogen receptor on breast and endometrial tissue. This has been shown to decrease the risk of breast and uterine cancer. Unfortunately, raloxifene is associated with increased risk for thromboembolic events.

PTH therapy is used in patients with severe osteoporosis, at least one fracture, and intolerance to bisphosphonates. While excessive PTH can lead to bone resorption, it can also lead to osteoblast activation if given in periodic doses rather than constantly. The exact mechanisms and pathway are not fully understood.

Calcitonin may be used to prevent compression fractures.

Paget

Paget disease, also known as osteitis deformans, is a disorder of bone remodeling that leads to abnormal bone formation.

In Paget disease, increased osteoclastic activity is later followed by increased osteoblastic activity with the deposition of disorganized bony architecture.

It is believed that Paget disease is caused by a slow viral infection, such as paramyxovirus or respiratory syncytial virus. There is also evidence that suggests a genetic basis for the disease.

Paget disease occurs most commonly in Caucasians and in the 5th decade of life.

The most common locations for Paget disease to develop include:

Femur

Pelvis

Tibia

Skull

Spine

Symptoms

Paget disease of bone presents with several orthopedic manifestations, which include:

Bone pain

Long bone bowing

Increased cranial diameter (which prompts a work-up if a patient complains their hat no longer fits)

Fractures due to abnormal bone architecture

Joint osteoarthritis

Paget diseaseof bone can result in deafness from changes in the auditory bones.

A potential non-orthopedic manifestation of Paget disease of bone is high output cardiac failure due to the increased vascularity of the disorganized bone architecture.

Diagnosis

Laboratory findings in Paget disease of bone include elevated serum alkaline phosphatase and urine hydroxyproline (a marker of collagen breakdown).

Paget disease has normal serum calcium levels.

X-ray imaging of Paget disease can demonstrate osteolytic lesions, sclerotic areas, and fractures.

A bone scan can accurately mark sites of disease in Paget disease by showing intensely hot lytic areas.

A rare complication of Paget disease is the development of secondary osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, or chondrosarcoma, which are listed in order of decreasing frequency.

Treatment of Paget disease of bone involves the use of bisphosphonates and calcitonin, which aim to decrease bone remodeling by slowing osteoclast activity.

Degenerative Disc

Degenerative disc disease refers to degenerative changes in the vertebral disc that lead to herniation of the central nucleus pulposus through the outer annulus fibrosis.

Disc herniation is most common at the levels of L4-L5 and L5-S1, but a cervical herniation can also occur.

The peak incidence of disc herniation is amongst people 40-50 years of age; they occur more often in men than women.

Symptoms

The clinical presentation of degenerative disc disease varies based on the vertebral level of the herniated disc, but can include sensory dysfunction, motor dysfunction, and pain.

Pain in disc herniation is typically radicular, meaning that it travels along the pathway of the nerve whose root is compressed.

Disc herniation of L4-L5 and L5-S1 usually leads to compression of L5 and S1 nerve roots, respectively, since the lumbosacral nerve root passes through the intervertebral foramen just inferior to the vertebrae of the same name. Therefore, disc herniation in this area affects the nerve root exiting the intervertebral foramen one level down (i.e., L4-L5 => L5).

Disc herniation of C6-C7, C7-T1, and T1-T2 usually leads to compression of C7, C8, and T1 nerve roots respectively since the cervical nerve roots pass through the middle of the intervertebral foramen. Note: Since there are seven cervical vertebrae and eight cervical nerve roots, no single rule (e.g., always the later nerve root like in the lumbosacral region) exists.

Sciatica, pain radiating down the path of the sciatic nerve, is a common manifestation of a herniated lumbar disc.

Physical exam findings of a herniated disc in degenerative disc disease include sensory and motor deficits and pain that worsens with a straight leg raise.

A motor exam is helpful in determining the level of disc herniation. Some nerve root motor associations of note include:

C5 – biceps reflex

C6 – brachioradialis reflex

C7 – triceps reflex

L4 – patellar reflex

S1 – Achilles reflex

The UW Neuroscience website provides a great table for reviewing nerve roots and the muscles innervated.

MRI is used to confirm the presence of a disc herniation.

Treatment

Treatment of a disc herniation in degenerative disc disease is typically nonoperative as 90% of patients improve without surgery.

The initial treatment of a disc herniation is:

Temporary activity modification

Resumption of activities as early as tolerated

NSAIDs or acetaminophen

Epidural anti-inflammatory injections if necessary

Patients with a disc herniation that causes persistent disabling pain can be treated surgically with a discectomy.

Osteoarthritis

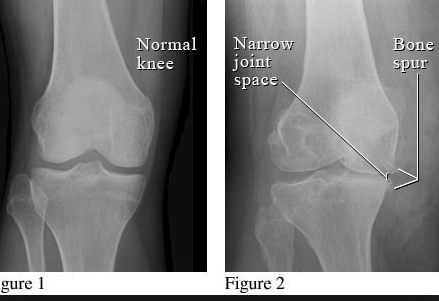

Degenerative joint disease, also known as osteoarthritis, is a chronic noninflammatory deterioration of articular cartilage.

As cartilage deteriorates, the underlying bone attempts to remodel and leads to a local inflammatory response and the eventual development of lytic lesions with sclerotic edges.

Degenerative joint disease can affect any synovial joint, but the most commonly affected locations are the knee, hand and hip in decreasing frequency.

Preventable risk factors for degenerative joint disease include:

Obesity

Trauma

Labor-intensive occupations

Non-modifiable risk factors for degenerative joint disease include:

Age

Family history

Female gender

Symptoms

The general presentation of degenerative joint disease involves joint pain and stiffness.

The joint pain in degenerative joint disease worsens with activity and weight bearing.

Degenerative joint disease can be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis, which improves with activity.

Physical exam findings in degenerative joint disease include:

Decreased range of motion

Effusion

Malalignment

Joint crepitus

DIP and PIP joint osteophytes with MCP sparing. Heberden's (DIP) and Bouchard's (PIP) nodes are commonly used eponyms.

Classic signs of degenerative joint disease that can be seen on x-ray can be remembered using the acronym JOSS:

Joint space narrowing

Osteophytes

Subchondral sclerosing

Subchondral cysts

Treatment

The first line of treatment for degenerative joint disease is acetaminophen if there are no signs or symptoms of inflammation. If acetaminophen is ineffective, or if inflammatory osteoarthritis is present, then NSAIDs should be used.

Other nonoperative treatment strategies for degenerative joint disease include:

Bracing

Weight loss in patients with BMI > 25

Physical therapy

Corticosteroid injection

Operative treatment strategies for degenerative joint disease include:

Arthroscopy in degenerative meniscal tears

Total joint replacement in advanced disease

Shoulder Dislocation

Shoulder dislocations are most commonly anterior dislocations (over 90%) and are generally a result of trauma.

The mechanism of injury in an anterior shoulder dislocation is a posteriorly directed force on the distal humerus or forearm during abduction, causing the humeral head to move forward and tear the anterior shoulder capsule.

Posterior shoulder dislocations most commonly occur during a seizure with the tetanic contraction of muscle being responsible for the dislocation.

Anterior shoulder dislocations present with an externally rotated and slightly abducted arm. Posterior dislocations present with an internally rotated and adducted arm.

The axillary artery and/or nerve can be damaged in shoulder dislocations, which should be suspected if there is deltoid weakness or shoulder numbness.

Treatment of shoulder dislocations requires immediate closed reduction. Chronic dislocations may require surgery to improve stability.

Hip dislocations are most commonly posterior dislocations which typically occur in younger patients due to high energy trauma.

The mechanism of a posterior hip dislocation is an axial load on the femur in a flexed and adducted hip. Think of a patient’s knee hitting the dashboard while in a motor vehicle collision.

Anterior hip dislocations are much more rare and occur with the hip in abduction and external rotation.

Posterior hip dislocations present as an internally rotated and adducted hip. Anterior hip dislocations present as an externally rotated and abducted hip.

Hip dislocations require emergent closed reduction with surgical reduction indicated if the dislocation cannot be reduced.

Osteomalacia

Osteomalacia (in adults) and rickets (in children) are bone pathologies that result from the impaired calcification of newly formed bone matrix (osteoid).

These conditions result from vitamin D deficiency due to lack of sunlight and/or poor diet in the absence of renal or metabolic defects.

The main function of Vitamin D is to reabsorb Calcium (and Phosphate) from the gut in order to maintain a solubility product adequate enough to mineralize bone. In Osteomalacia and Rickets, Vitamin D deficiency decreases serum Calcium, which causes:

Hypocalcemic tetany (hypertonia)

Increased parathyroid hormone secretion causing decreased serum Phosphate

Decreased mineralization of osteoid, which causes soft bones with decreased bone density and increased unmineralized osteoid matrix with widening between osteoid seams

Osteomalacia and rickets are qualitative defects in bone formation - the process of bone mineralization is abnormal. Comparatively, a defect like osteoporosis is a quantitative defect in bone formation - bone loss occurs despite normal mineralization.

Causes

General causes of vitamin D deficiency include:

Poor intake

Increased loss of vitamin D

Impaired 25-hydroxylation

Impaired 1-alpha-hydroxylation

Target organ resistance

Cause of vitamin D deficiency associated with poor intake include:

Impaired cutaneous production

Vitamin D deficient diets

GI disorders (eg, prolonged cholestasis) which result in malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins, including vitamin D

Cause of vitamin D deficiency associated with increased Loss of Vitamin D include:

Increased metabolism (barbiturates, phenytoin, rifampin)

Impaired enterohepatic circulation

Nephrotic syndrome

Cause of vitamin D deficiency associated with impaired 25-hydroxylation include:

Liver disease

Isoniazid

Cause of vitamin D deficiency associated with impaired 1α-hydroxylation include:

Renal osteodystrophy: chronic renal failure leads to decreased 1-α-hydroxylase activity which causes decreased 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D

Enzyme mutation

Hypoparathyroidism

X-linked hypophosphatemic Rickets

Oncogenic osteomalacia

Ketoconazole

Aluminum-containing phosphate-binding antacids (eg, Aluminum Hydroxide)

Cause of vitamin D deficiency associated with target organ resistance include:

Vitamin D receptor mutation

Phenytoin

Rickets

In Rickets, failure of mineralization leads to changes in the growth plate (the epiphyseal cartilage becomes hypertrophic without calcification) and bone (cortical thinning, bowing).

Clinical findings specific to rickets (i.e., not found in osteomalacia) include:

Genu varum, which is lateral bowing of weight bearing bones

Rachitic “rosary chest,” which is a bony prominence at costochondral junctions

Harrison’s sulci, which are indentations in lower ribs

Craniotabes, which is softening of skull bones

Growth retardation due to defective mineralization at growth plates of long bones

Lab values seen in rickets include:

Decreased 25(OH) vitamin D (storage form)

Decreased calcium

Decreased phosphate

Increased alkaline phosphatase

Increased parathyroid hormone (PTH)

X-ray imaging will show:

Widening of physes

Bowing of long bones

Translucent lines in bones

Flattening of the skull

Enlarged costal cartilages

Treatment

Treatment of Vitamin D deficiency should be based on the underlying cause and severity, and repletion should always be done with calcium supplementation.

Phosphorus supplementation should be given for all types of impaired calcification.

For dietary causes, pharmacologic repletion of vitamin D (50,000 IU weekly) for 3-12 weeks followed by maintenance therapy (800 IU daily) is recommended.

For impaired 1α-hydroxylation, give the active form, 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D.

Calcium supplementation should be 1.5-2 g/d.

Pharmacologic doses (50,000 IU weekly) of vitamin D may be necessary for maintenance therapy in patients taking drugs causing increased metabolism and/or impaired hydroxylation.

Osteomalacia may be reversible if vitamin D is replaced. Although Rickets is partly reversible with vitamin D replacement, some of the pathology specific to Rickets (eg, growth retardation) may not be completely overcome by vitamin D supplements.

Iatrogenic causes may require withholding the offending medication.

Osteopetrosis

Osteopetrosis is a rare hereditary bone disorder caused by impaired osteoclast activity, which results in abnormally thick bones.

In the autosomal dominant form of osteopetrosis, known as Albers-Schonberg disease, the inability of osteoclasts to produce carbonic anhydrase II impairs their ability to break down bone. This is typically the mildest form of osteopetrosis.

The autosomal recessive, or “infantile,” form of osteopetrosis is much more severe and is fatal within the first few months of life due to bone marrow impairment as a result of dense bones.

There is a third form of osteopetrosis called osteopetrosis tarda that is generally a benign condition and often does not require treatment.

Osteopetrosis is commonly associated with cranial nerve palsies, producing symptoms related to the following cranial nerves in order of decreasing frequency:

Optic

Auditory portion of vestibulocochlear

Trigeminal

Facial

Symptoms

Symptoms of the autosomal dominant form of osteopetrosis may be silent until adulthood when anemia and pathologic fractures may present.

Symptoms specific to the autosomal recessive form of osteopetrosis include:

Frequent fractures

Deafness, due to CN VIII compression

Blindness, due to CN II compression

Anemia

Physical exam findings of osteopetrosis primarily consist of cranial nerve palsies.

Diagnosis

Serum laboratory findings in osteopetrosis include:

Increased tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), due to increased release from defective osteoclasts

Increased alkaline phosphatase, due to increased osteoblast activity

Increased creatine kinase BB, due to increased release from defective osteoclasts

Decreased hematocrit and hemoglobin

X-ray imaging shows increased bone density in osteopetrosis.

Histological findings of osteopetrosis show osteoclasts that lack a ruffled border and clear zone.

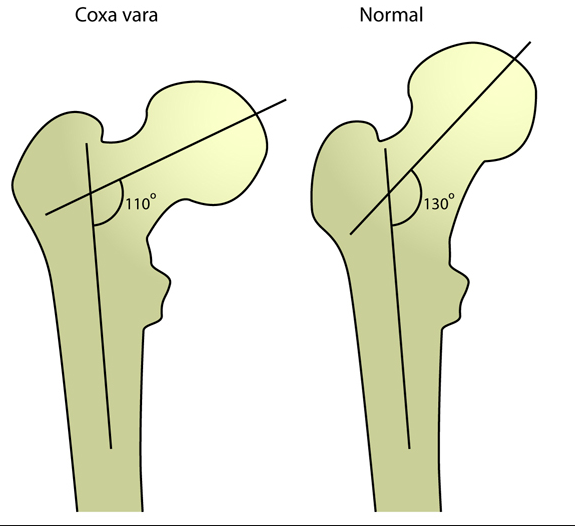

Complications of osteopetrosis include osteomyelitis, long bone fractures, and coxa vara (a decrease in the normal angle between the femoral head and shaft).

Treatment

Treatment of the autosomal dominant form of osteopetrosis involves the use IFN-y-1b.

Treatment of the autosomal recessive (infantile) form of osteopetrosis includes calcitriol, bone marrow transplant, and activity restriction.

Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis is a narrowing of the spinal canal or intervertebral foramina in the cervical or (less commonly) lumbar regions, resulting in nerve compression.

Spinal stenosis is generally the result of degenerative/spondylotic changes to the spine.

Other causes of spinal stenosis include:

Facet osteophytes

Herniated discs

Synovial facet cysts

Ankylosing spondylitis

Spinal stenosis is most common amongst middle-aged and older adults, but can also occur in people with genetic diseases like achondroplasia.

Symptoms

The clinical presentation of spinal stenosis includes a variety of neurological symptoms, including:

Back pain

Referred buttock pain

Neurogenic claudication (pain in legs while walking)

Weakness

Neurogenic claudication can be differentiated from the claudication of peripheral vascular disease because it is:

Relieved in flexion (e.g. by leaning over a shopping cart)

Worse in extension (e.g. by standing up straight or walking)

During a physical exam, a positive Kemp sign is found in spinal stenosis, which is unilateral radicular pain that is made worse by extending the patient’s back or neck.

Diagnosis

Straight leg raise is negative in pure spinal stenosis. A positive straight leg raise in a patient with spinal stenosis indicates involvement of the nerve roots as well as the spinal cord, and may be seen in patients with herniated discs or degenerative disc disease.

MRI is the diagnostic modality of choice in lumbar spinal stenosis. X-ray can support a diagnosis of lumbar spinal stenosis but is not as accurate as MRI.

Treatment

Nonoperative treatment of spinal stenosis includes NSAIDs, physical therapy, and epidural corticosteroid injections.

Operative treatment of spinal stenosis consists of pedicle decompression, also known as a laminectomy, with or without instrumented fusion. This is indicated if nonoperative treatment fails.

Bone Cancer

Bone Metastases

Bone Metastases are the most common bone tumor that affects adults and can be lytic or blastic lesions.

Metastases to bone can result from nearly any type of primary tumor. The most common primary tumors that metastasize to bone include:

Breast

Lung

Thyroid

Renal

Prostate

Which can be remembered using the mnemonic Bone Loving Tumors Really Punish

Bone is the third most common site for metastases, behind lung and liver.

The most common location for a metastatic bone lesion to occur is the thoracic spine because of the valveless nature of Batson’s vertebral plexus.

Symptoms of metastases to bone include bone pain, pathological fracture, and metastatic hypercalcemia.

Physical exam findings of bone metastases generally involves neurological deficits due to compression of the spinal cord by the lesion. Remember that the spine is the most common location of bony mets.

In bone metastases, a bone biopsy is required in order to determine the site of the primary tumor.

X-ray imaging is useful in identifying the presence of a bone metastasis. Bone scans are useful to determine the extent of a lesion.

Lytic lesions visible on x-ray suggest a primary lung, thyroid, or renal tumor.

Blastic lesions usually suggest breast or prostate cancer, but remember that breast can sometimes be lytic.

Treatment of bone metastases varies based on the specific patient circumstances, but includes:

Chemotherapy

Bisphosphonates to slow the progression of bone loss

Radiation to decrease the size of the metastasis

Fixation of fractures, with prophylactic fixation of impending fractures

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumor, but it can also occur as a result of other primary diseases, such as Paget’s disease of bone.

Osteosarcoma is most common amongst young male patients.

The most common locations for the development of osteosarcoma are the distal femur, proximal tibia, or proximal humerus.

Genetic conditions that predispose to osteosarcoma include:

p53 genetic mutations

Familial retinoblastoma (Rb gene mutations)

Non-genetic conditions that predispose to osteosarcoma include:

Paget’s disease of bone

Bone infarcts

Radiation exposure

Before diagnosing osteosarcoma, tumors that metastasize to bone from other areas should be ruled out. These include the following:

Breast

Lung

Thyroid

Renal

Prostate

Which can be remembered using the mnemonic Bone Loving Tumors Really Punish. These are secondary bone cancers and not true osteosarcomas.

Symptoms

Osteosarcoma generally presents with pain and 25% of patients present with pathologic fracture.

Physical exam findings in osteosarcoma can include local tenderness, soft tissue swelling, and the development of a palpable bony mass.

Diagnosis

Laboratory findings in osteosarcoma include increased alkaline phosphatase, ESR, and LDH.

Bone biopsy provides the definitive diagnosis in cases of osteosarcoma.

X-ray imaging of osteosarcoma can show a “sunburst” periosteal pattern and an elevation of the periosteum commonly referred to as Codman’s triangle.

Complications of osteosarcoma include a high risk of pulmonary metastasis.

Chest CT scans are commonly performed in patients with osteosarcoma to look for metastases.

A low-grade osteosarcoma has a 90% 5 year survival rate. A higher-grade osteosarcoma has a 50% 5 year survival rate.

Treatment of osteosarcoma is radical surgical excision of the lesion and chemotherapy.

Osteochondromas

Osteochondromas are most commonly found in the metaphysis of long bones; most commonly the femur or proximal tibia.

Osteochondromas are typically found near growth plates and act like isolated growth plates in response to hormones and growth factors.

Osteochondromas are most common in male patients under the age of 25.

Osteochondroma is the most common benign bone tumor.

Symptoms

An osteochondroma typically presents as a nontender, nonpainful hard mass found near the knee. If pain is present, it is generally from tissue irritation due to the mass.

Since osteochondromas act similarly to growth plates, their growth generally ceases when skeletal maturity is reached.

On physical examination, an osteochondroma will be a hard palpable mass that may or may not have tenderness from soft tissue irritation.

X-rays of an osteochondroma show bone mass growing out from the metaphyseal region. MRI can distinguish malignancy, which is determined when the bone mass is not continuous with the normal cancellous bone.

A rare complication of an osteochondroma is a transformation into a chondrosarcoma.

No treatment is generally necessary for an osteochondroma as most patients are asymptomatic. A symptomatic osteochondroma is treated with surgical resection.

Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma is a distinctive small, round, blue cell tumor of bone that is highly malignant.

Ewing sarcoma occurs due to a t(11:22) translocation, which creates the EWS-FLI fusion protein.

Ewing sarcoma commonly occurs in the diaphysis of long bones and in the pelvis.

Ewing sarcoma is most common amongst patients who are 5-25 years of age.

In children less than 10 years of age, Ewing sarcoma is more prevalent than osteosarcoma.

Ewing sarcoma typically presents with pain and fever, which often mimics an infection.

Other symptoms of Ewing sarcoma include:

Bone pain

Fatigue

Weight Loss

Fractures from microtrauma

Physical exam findings in patients with Ewing sarcoma include tissue swelling and tenderness. Sometimes a palpable mass is present.

Serum laboratory findings in Ewing sarcoma show:

Increased ESR

Increased WBCs

Decreased Hgb

A bone biopsy is required to make the diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma.

X-ray imaging in Ewing sarcoma shows a destructive lesion in the diaphysis and/or metaphysis of long bones with a classic “moth-eaten appearance.” A periosteal reaction in Ewing sarcoma may show periosteal elevation or “onion-skin” lesions on x-ray imaging.

Ewing sarcoma has a 60% 5-year survival rate when combined radiation and chemotherapy are used in non-metastatic cases, but a 20% 5-year survival rate if metastases are present.

Treatment of Ewing sarcoma involves radiation, chemotherapy, and limb salvage resection of the affected bone.

Other Autoimmune

Gout

Gout is a form of arthritis caused by the deposition of monosodium urate crystals into joints, bones, and soft tissues.

Primary gout is the result of hyperuricemia due to nucleic acid metabolism disorders (e.g. Lesch-Nyhan syndrome) and/or underexcretion of uric acid, leading to deposition of monosodium urate.

Secondary gout is associated with diseases that have high metabolic turnover, such as leukemia or psoriasis.

Gout is most common in men aged 40-60 years old.

Causes of overproduction of uric acid associated with gout are obesity, cancer, and hemoglobinopathies.

Causes of underexcretion of uric acid associated with gout include renal disease and the use of loop or thiazide diuretics.

Symptoms

Gout presents with sudden sharp pain in the affected joint; some patients also present with fever.

The most commonly affected joint is the first metatarsophalangeal joint, which, when affected by gout, is referred to as podagra.

On physical exam, patients with gout will have a red, swollen, and extremely painful joint with decreased range of motion due to pain.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of gout is made when needle-shaped, negatively birefringent crystals are found in joint aspiration.

On polarizing light microscopy, the negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals of gout appear:

Yellow when parallel to the polarizing axis

Blue when perpendicular to the polarizing axis

Elevated uric acid is not diagnostic of gout, as most people with elevated uric acid will never develop gout.

In chronic cases of gout, x-ray imaging may show bony erosions and soft tissue crystal deposition, known as tophi.

Synovial fluid analysis in patients with acute gout reveals an elevated leukocyte count (2,000-100,000cells/mm3) with neutrophil predominance.

Complications of chronic gout involve the formation of large tophi, leading to permanent deformity.

Treatment

The first-line treatment for acute gout is NSAIDs (e.g. naproxen, indomethacin).

Note that aspirin is avoided in this setting since it reduces renal uric acid clearance at low doses (2-3g/day).

Additional treatment options for acute gout include the microtubule inhibitor colchicine and glucocorticoids.

Three classes of agents used in the treatment of chronic gout are:

Xanthine oxidase inhibitors (e.g. allopurinol, febuxostat)

Uricosuric agents (e.g. probenecid, sulfinpyrazone)

Recombinant uricases (e.g. pegloticase, rasburicase)

The choice of which class of urate-lowering drug to use in patients with chronic gout is guided by 24 hr. urine uric acid excretion. Generally, the following agents are used:

Uricosuric agents (e.g. probenecid) in patients that excrete <800 mg of uric acid/day

Xanthine oxidase inhibitors (e.g. allopurinol) in patients that excrete >800 mg of uric acid/day

Probenecid is contraindicated in patients with a history of nephrolithiasis since it is associated with the formation of renal stones.

Allopurinol is associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Pseudogout

Pseudogout is characterized by calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate deposition in joints.

Patients at risk for pseudogout include those with current endocrine disorders, such as diabetes mellitus and hyperparathyroidism.

Pseudogout presents similarly to gout, with the knee and wrist most commonly affected. However, the symptoms of pseudogout are less severe than gout.

The symptoms of pseudogout include pain, swelling, heat, and redness. Roughly half of patients with pseudogout will experience fever.

Podagra, a very rapid inflammation of the big toe, rules out pseudogout and instead suggests that gout is present.

Physical exam findings include a tender, acutely inflamed joint with pain during range of motion testing.

DDD Diagnosis

Laboratory findings in pseudogout yield joint aspiration with crystals that are positively birefringent (blue color when aligned parallel to the slow axis), which distinguishes them from the negatively birefringent (yellow color when aligned parallel to the slow axis) urate crystals seen in gout. The crystals seen in pseudogout appear more rhomboidal than those in gout.

Chondrocalcinosis may be seen on X-ray in patients with pseudogout, which is calcification within the cartilage of joints.

A complication of pseudogout is increased risk of osteoarthritis in the affected joints.

Treatment for pseudogout includes NSAIDs and colchicine to prevent episodes from recurring.

Sjogren

Sjögren syndrome is a chronic autoimmune disorder with exocrine gland dysfunction and dry mucosal surfaces (sicca symptoms).

The typical patient is female and between forty and fifty years old.

It is the second most common autoimmune rheumatic disorder.

Sjögren syndrome is associated with other autoimmune conditions and may be associated with CMV and EBV.

Sjögren syndrome has an insidious presentation featuring at least one of the following:

Sicca symptoms like xerophthalmia and xerostomia

Nonspecific symptoms like fatigue, sleep issues, anxiety, or depression

Systemic symptoms like musculoskeletal, pulmonary or GI

Diagnosis

Sjögren syndrome has several diagnostic criteria systems, but you should suspect Sjögren syndrome in patients with sicca symptoms and at least one of the following:

Anti-SS-A or anti-SS-B antibodies

Chronic inflammatory infiltrate in salivary exocrine glands

Indications of systemic involvement

You must rule out other causes of sicca systems, which can be caused by a long list of things from age to diabetes to HIV to medications.

The Schirmer test can be used to test tear function.

Blood tests generally show an elevated ESR and cytopenia, but the stereotypical antibodies are anti-Ro and anti-La.

Salivary gland biopsy may be necessary if no antibodies are found or the patient desires something beyond symptomatic treatment.

Sjögren syndrome’s complications result from its sicca symptoms.

Xerostomia deprives the oral cavity of saliva, which allows bacterial overgrowth that results in:

Caries

Candidiasis

Sialadenitis

Periodontal disease

Xerophthalmia leads to:

Corneal ulceration

Eyelid infections

Destroyed conjunctival epithelium

Sjögren syndrome patients are at an increased risk of hematologic malignancy like mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

If the patient has systemic manifestations, then complications will be associated with the particular system involved. For instance, pulmonary involvement could lead to COPD; whereas, cardiovascular involvement could lead to pericarditis.

There is an increased risk of congenital heart block in a pregnant Sjögren syndrome patient’s fetus.

Treatment

There is no cure for Sjögren syndrome; therefore, treatment is for symptoms only.

Xerophthalmia is treated with preservative-free artificial tears or topical ocular glucans. If severe enough, topical cyclosporine A or punctual occlusions like plugs, cauterization, or surgery may be indicated.

Xerostomia is treated with mechanical stimulation or saliva substitutes. Medications like pilocarpine or cevimeline improve salivary flow. Antimicrobial mouth rinses and daily fluoride use is necessary to prevent the oral complications.

Vitamin D supplementation should be considered.

Patients should avoid foods (e.g., coffee and alcohol) and activities (e.g., nicotine and smoke) that increase sicca symptoms.

Patients should practice good oral hygiene, chew gum or suck lozenges to increase saliva, and maintain fluid intake.

Scleroderma

Scleroderma (also called systemic sclerosis) is a chronic connective tissue disease with an unknown cause that affects skin, subcutaneous tissue, and internal organs.

The most commonly affected internal organs:

GI tract (90%)

Lungs (70%)

Musculoskeletal (45-68%)

Heart, vessels, kidneys

Scleroderma typically presents between ages twenty and fifty.

Scleroderma is four-times more common in women, with black women having twice the incidence of white women.

The two main forms of scleroderma are limited (60%) and diffuse (35%).

Scleroderma is associated with primary biliary cirrhosis and malignancies (esophageal, lung, skin, and oropharyngeal).

Scleroderma pathogenesis involve soverproduction of extracellular matrix components, microvascular dysfunction, and dysfunctional cell/humoral immunity.

Symptoms

Skin is the most commonly involved organ in scleroderma. Patients with scleroderma have thick, tight, and shiny skin and may develop a "mask like" face due to increased dermal thickening.

Raynaud phenomenon is present in 95% of scleroderma patients.

Scleroderma-related musculoskeletal discomfort presents as myalgia, arthralgia, myositis, and swelling. Musculoskeletal changes are the result of local skin involvement causing joint contractures.

Scleroderma-related GI symptoms often present as diarrhea or constipation and esophageal disease.

The most common GI manifestation of systemic sclerosis is esophageal hypomotility and concomitant incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter, which is caused by smooth muscle atrophy and fibrosis in the distal esophagus.

This presents as dysphagia and gastroesophageal reflux.

Esophageal reflux and esophageal candida are common, and are related to decreased esophageal motility.

Endoscopy often shows:

Wide mouth colonic diverticula

Patulous (distended or widened) esophagus

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (“watermelon stomach”).

Systemic sclerosis can cause interstitial and perivascular fibrosis in the kidneys. The resultant arteriolar vasculitis and glomerulitis can cause scleroderma renal crisis, which manifests with:

Sudden-onset hypertension

Papilledema

Azotemia

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia

Hematuria, proteinuria

Before the introduction of ACE inhibitor treatment, scleroderma renal crisis was a common cause of death in patients.

Cardiac involvement of scleroderma can result in areas of myocardial fibrosis, potentially resulting in congestive heart failure and/or arrhythmias.

Interstitial fibrosis is the most common cause of pulmonary complications in patients with systemic sclerosis. Other complications include:

Pleural effusions

Alveolitis

Pulmonary hypertension and Cor pulmonale

Pleurisy

Spontaneous pneumothorax

The limited subtype (60% of scleroderma patients) presents with the CREST mnemonic:

Anti-Centromere antibody (not seen in diffuse scleroderma) and skin Calcification

Raynaud phenomenon

Esophageal dysmotility

Sclerodactyly

Telangiectasia

Diagnosis

Most patients with scleroderma have positive antinuclear (ANA) antibodies; more specific autoantibodies include:

Diffuse scleroderma: antitopoisomerase I (anti-Scl-70)

Limited scleroderma: anticentromere

Treatment

There is no cure for scleroderma, and treatment is based on organ involvement.

Physical therapy helps reduce joint contracture.

Esophageal reflux is treated with standard reflux therapy (proton pump blockers, H2 blockers). Esophageal strictures may require surgical correction.

Promotility agents help with GI symptoms, and metronidazole can decrease malabsorption due to bacterial overgrowth.

ACE inhibitors can delay, prevent, and even reverse uremia in patients with scleroderma renal crisis.

Vasodilators are used for sclerotic vessel conditions like Raynaud phenomenon.

Cyclophosphamide and steroids can help in cases of a rapidly progressive scleroderma.

SLE

SLE (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus) is a chronic multisystem autoimmune disorder involving a variety of autoantibodies that usually damages skin, joints, kidneys, and serosas.

Lupus is a type III hypersensitivity reaction (with the exception of associated blood disorders), which involves antibody-mediated attack of deposited antigen-antibody complexes in affected tissues.

/Risk factors associated with SLE include:

Young women (highest incidence and prevalence)

African Americans

Asians

Hispanics

Drug-induced lupus can present with similar symptoms and resolves when the offending drug is discontinued. Slow acetylators are predisposed with medications that are metabolized via acetylation. In drug induced lupus there is no CNS or renal involvement, and the patient will only have anti-histone antibodies, not anti-dsDNA and others.

Drugs that are commonly associated with drug-induced lupus include (mnemonic: Having lupus is SHIPP-E):

Sulfa drugs

Hydralazine

Isoniazid

Procainamide

Phenytoin

Etanercept

All SOAP BRAIN MD diagnostic criteria involve tissue damage mediated by immune-complex Type III hypersensitivity, except for the Blood disorders (hemolytic anemia with reticulocytosis, thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, leukopenia) which are mediated by Type II hypersensitivity.

Serositis

Oral ulcers

Arthritis (>2 joints)

Photosensitivity (sun-induced rashes)

Blood disorders (anemia, thromocytopenia, and leukopenia)

Renal disorder (lupus nephritis)

ANA positive (sensitive not specific)

Immunologic (anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, lupus anticoagulant)

Neurologic disorders (seizures, psychosis)

Malar “butterfly” rash

Discoid rash

Another mnemonic to remember the features of SLE is RASH ORR PPAIN:

Rash (malar or discoid)

Arthritis

Soft tissues/serositis

Hematologic disorders

Oral/nasopharyngeal ulcers

Renal disease

Raynaud phenomenon

Photosensitivity

Positive VDRL/RPR

Antinuclear antibodies

Immunosuppressants

Neurologic disorders (e.g. seizures, psychosis)

Serositis is associated with the following:

Pleuritis, including pleuritic pain (knife-like pain during inspiration) or pleural effusion

Pericarditis

Pneumonitis

Oral or nasopharyngeal ulcers are commonly associated with SLE.

Arthritis, when associated with SLE, includes ≥2 peripheral joints. [Note: In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, the arthritis in SLE is nonerosive with little deformity]

Photosensitivity is associated with SLE, which can result in not only a rash when exposed to sunlight, but fever, fatigue, and joint pain.

Blood disorders associated with SLE are a type II hypersensitivity reaction and include:

Hemolytic anemia with reticulocytosis

Thrombocytopenia

Lymphopenia

Leukopenia

Renal disorders of SLE are associated with proteinuria or cellular casts and include:

Class IV lupus nephritis: diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis (nephritic) — most common and most severe form of lupus nephritis; commonly has “wire-loop” lesions due to prominent subendothelial immune-complex deposits

Class V lupus nephritis: membranous glomerulonephritis (nephrotic)

ANA positive titer is found in 95% of patients with SLE. It is sensitive, but not specific for lupus.

Immunological disorders associated with SLE include:

Anti-dsDNA antibody which is very specific for SLE and correlated with poor prognosis

Anti-Sm antibody, which is very specific for SLE, but not correlated with prognosis

SLE is commonly associated with APLS (anti-phospholipid syndrome)

Decreased complement (C3 and C4)

Neurologic disorders associated with SLE include seizures, psychosis, stroke, or neuropathy.

Malar “butterfly” rash is associated with SLE, which is malar eminence erythema and it usually spares nasolabial folds.

Discoid rash is another rash associated with SLE that is red raised patches with follicular plugging and keratotic scaling.

All SOAP BRAIN MD diagnostic criteria (listed above) involve tissue damage mediated by immune-complex Type III hypersensitivity, except for the blood disorders (hemolytic anemia with reticulocytosis, thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, leukopenia) which are mediated by Type II hypersensitivity.

SLE patients may have false-positive serologic tests for syphilis (eg, RPR or VDRL) due to antiphospholipid antibodies that cross-react with the beef cardiolipin used in these tests.

Treatment of SLE is based upon the presentation and includes:

Avoidance of sun if photosensitive

NSAIDs for pain

Hydroxychloroquine for skin symptoms

Corticosteroids for immunosuppression and to decreases exacerbations (note: other immunosuppressants may be used if corticosteroid resistant)

Anticoagulation if the patient is hypercoagulable

The most worrisome complication of SLE is infection (secondary to immunosuppression), which is the most common cause of death in SLE patients who receive treatment. Note: in patients who are not medically treated, renal failure and cardiovascular disease are the most common causes of death.

Other complications associated with SLE include:

Libman-Sacks Endocarditis (nonbacterial verrucous endocarditis), which vegetations are found on both sides of cardiac valves - this is easily remembered by saying “SLEcauses LSE”

Recurrent spontaneous abortions secondary to antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-beta-2 glycoprotein)

Anti-Ro/SS-A antibody (anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies occur in 30-50% of SLE patients), which may cross the placenta and induce the destruction of the cardiac AV node and conduction system in the neonate causing congenital complete heart block.

Interstitial lung fibrosis

Carpal Tunnel

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a disorder that results from the compression of the median nerve within the carpal tunnel of the wrist, leading to pain and paresthesias.

The basic mechanism involves compression of the median nerve which results in ischemia and disruption of nerve conduction. The mnemonic MICE can help you remember some of the most common mechanisms:

Mass lesions

Inflammation (of the flexor tendons or from systemic inflammatory disease like rheumatoid arthritis)

Congenitally small compartments

Edematous conditions such as hypothyroidism or pregnancy

Wrist extension and extreme flexion place additional strain on the compartment, so the patient is more symptomatic. Pressures are lowest when the wrist is in a neutral or slightly flexed position, so the patient is less symptomatic.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is associated with repetitive hand motions such as driving, holding a telephone, reading, and typing. Use of vibrating tools and motions involving large amounts of force have also been implicated.

Carpal tunnel syndrome is most common in females, especially in those that are obese and/or diabetic.

The key clinical feature of carpal tunnel syndrome is pain and/or paresthesia in the area supplied by the median nerve.

Recall that the median nerve provides sensation to the first three digits of the hand and the radial half of the fourth digit.

Atypical presentations of carpal tunnel syndrome can include pain over the entire hand or pain localized to the wrist.

Symptoms can worsen at night and can awaken the patient from their sleep.

Progression of untreated disease may result in weakness of thenar muscles which may manifest as difficulty grasping small objects.

The diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome is largely made on the basis of history and physical exam. The history typically includes risk factors such as repetitive motion or hypothyroidism, and physical exam often reveals a positive Phalen maneuver or Tinel test.

Patients often have a history of repetitive wrist or forearm motion such as typing, writing, or knitting. Tasks involving high force, vibration, and cold temperatures are also risk factors.

The Phalen maneuver and Tinel test are indicated in the physical examination of patients with wrist pain, and can further support a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Phalen maneuver: forced flexion of the dorsal surfaces of the hands against each other for 30-60 seconds resulting in pain or paresthesia in the distribution of the median nerve suggests carpal tunnel syndrome.

In a positive Tinel test, percussion above the course of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel results in pain or paresthesia in median nerve distribution.

Other tests include compression of the carpal tunnel or elevation of the hands above the head. In either case, carpal tunnel syndrome is likely if the patient reports pain or paresthesia.

The definitive test for establishing the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome is a nerve conduction study.

Electromyography (EMG) can be obtained as a supplement to NCS to rule out polyneuropathy, plexopathy, or radiculopathy but does not directly support a diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome.

Treatment

With treatment, carpal tunnel syndrome is unlikely to produce any sequelae. Untreated, there may be permanent nerve damage and worsening of symptoms.

Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome depends on severity; treatment is approached in a progressive manner starting with least invasive.

Initial management of carpal tunnel syndrome consists of splinting, especially at night.

Cases refractory to splinting may be treated with glucocorticoid injection into the carpal tunnel.

If local glucocorticoid injections are unsuccessful, oral glucocorticoids may be used as the last line in non-surgical management.

Surgical decompression of the carpal tunnel via division of the transverse carpal ligament is reserved for patients in whom splinting, glucocorticoid injections and oral glucocorticoids are unsuccessful.

Physical therapy may help to control symptoms and may be attempted in conjunction with other treatment modalities.

Ligament Tears

Ligament tears are the result of excessive stress across the affected joint.

The clinical presentation of a torn ligament is pain and swelling that worsens with joint stress.

Physical exam findings present with a torn ligament are decreased joint range of motion and instability on joint stress testing.

Obtaining an MRI of a torn ligament can confirm the presence of a tear.

Torn ligaments are initially treated like sprains (which, aside from Grade III sprains, are stretching/partial tears of a ligament), using analgesics and RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation). More serious ligament tears can require surgical intervention.

MCTD

Mixed Connective Tissue Disease (MCTD) is a systemic autoimmune syndrome that combines features of:

SLE

Polymyositis

Dermatomyositis

Scleroderma

Rheumatoid arthritis

MCTD typically affects women.

Pathogenesis is thought to be related to anti-U1-ribonucleoprotein (anti-U1-RNP), though no direct evidence supports this association.

MCTD can present in a variety of ways because it is the intersection of many autoimmune conditions.

Patients may have nonspecific constitutional symptoms like fever, fatigue, or headache.

Patients may present with skin changes like Raynaud phenomenon or a malar rash.

Patients may present with joint, muscle, GI, or pulmonary symptoms.

Children will often present with Raynaud phenomenon, fatigue, and pain.

MCTD is diagnosed by specific criteria that assess serologic and clinical findings.

There are four sets of criteria; however, the Alarcón-Segovia criteria is the most common.

Serologic and at least three clinical criteria are required.

Serologic criteria—anti-U1-RNP titer > 1:1,600

Clinical criteria—synovitis or myositis (required), hand edema, Raynaud phenomenon, and acrosclerosis.

Rule out other connective tissue diseases and fibromyalgia in all patients.

Rule out occult infection and malignancy in patients with fever.

MCTD complications depend on the organ system affected.

In the lung, MCTD can cause PAH or interstitial lung disease.

In the cardiovascular system, MCTD can cause heart failure, stroke, or vasculitis.

In the renal system, MCTD can cause mesangial or membranous glomerulonephritis. Twenty-five percent of MCTD patients have asymptomatic renal involvement.

MCTD patients can also develop GI bleeding, malabsorption syndrome or bowel perforation from the vasculitis, CNS impairment, and rarely a hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis.

MCTD is believed to be uncurable; therefore, management is guided by the patient's clinical manifestations of similar problems seen in patients with SLE, scleroderma, or polymyositis and using treatment known to be effective in those conditions.

Skin conditions can be treated with topical corticosteroids.

NSAIDS or low-dose corticosteroids can treat the fever, fatigue, myalgia without myositis, and mild joint pain.

Careful, long-term follow-up to check:

Blood pressure (due to cardiovascular manifestations of the disease)

CBC(to check for anemia due to GI bleeding)

Muscle enzymes (to assess muscle breakdown)

Urine protein (to assess renal involvement)

and other markers of disease progression is necessary.

Polyarteritis Nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis of the medium-sized muscular arteries in which segmental transmural inflammation leads to fibrinoid necrosis. Veins are not affected.

The most significant risk factor for polyarteritis nodosa appears to be infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), though the disease may also occur with increased incidence in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and hairy cell leukemia. Nevertheless, most cases are idiopathic.

The transmural inflammation from PAN leads to narrowing of the arterial lumen, thrombosis, and weakening of the arterial wall which can lead to an aneurysm.

PAN commonly affects:

Kidneys

Heart

GI tract

Muscles

Nerves

Joints

Risk factors associated with PAN include:

Hepatitis B or C

Increasing age

Male gender

Polyarteritis nodosa generally presents in middle-aged and older adults with systemic symptoms (fatigue, fevers, weight loss, arthralgias, myalgias) and evidence of multisystem organ damage.

Symptoms