20 Orthopedics

Axial Skeleton Fracture

Pathogenesis

Rib fractures include fractures of any of the 10 pairs of non-floating ribs.

Rib fractures are generally the result of trauma and can be associated with hemothorax or pneumothorax.

Symptoms

Patients with rib fractures have painful breathing and may have bruising over the rib area. Uncomplicated fractures without evidence of internal organ injury (no hypotension, chest wall deformity, abdominal pain, or pneumothorax on chest x-ray).

Diagnosis

Up to half of rib fractures will not be evident on initial chest x-ray; therefore, the diagnosis should be highly suspected in all patients with localized chest wall tenderness following trauma.

Treatment

Rib fractures cannot be casted and patients are usually treated with pain control. If a flail chest segment is present (three or more consecutive fractured ribs), open reduction internal fixation is indicated.

Maintaining adequate ventilation is the main goal of rib fracture management. Rib fractures are typically associated with significant pain, which causes hypoventilation that may lead to atelectasis and pneumonia. Pain control is essential to maintain deep breathing and adequate cough. For extensive rib fractures managed as an inpatient, epidural infusion is the preferred method of pain control. Intercostal nerve blocks are also used but carry the risk of iatrogenic pneumothorax during administration. Patients with less extensive rib fractures (such as this patient) can be managed with a combination of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (eg, ketorolac, ibuprofen) and opioids. Opioids have the disadvantage of central respiratory depression, but this disadvantage is typically outweighed by the benefits of adequate pain control.

If a flail chest segment is present (three or more consecutive fractured ribs), open reduction internal fixation is indicated. Positive airway pressure is indicated in the case of flail chest (fracture of>3 consecutive ribs in >2 places) as it corrects the paradoxical respiratory motion of the isolated segment of chest wall and improves oxygenation of fluid-filled alveoli (often present due to associated pulmonary contusion). However, positive airway pressure is not indicated in the management of an uncomplicated rib fracture.

Prophylactic antibiotics are not routinely indicated in the management of rib fractures unless an open fracture has occurred.

Upper Extremity Fractures

Clavicle

The clavicle is one of the most commonly injured bones in the body. The majority of clavicular fractures occur in the middle third of the bone. Injury to this bone classically occurs during athletic events and follows a fall on an outstretched arm or a direct blow to the shoulder. Patients with clavicular fractures present with pain and immobility of the affected arm. The contralateral hand is classically used to support the weight of the affected arm. The shoulder on the affected side is displaced inferiorly and posteriorly. A careful neurovascular exam should accompany all fractures to the clavicle due to its proximity to the subclavian artery and brachial plexus. In this case, a bruit is heard and an angiogram is necessary to rule out injury to the underlying vessel.

Fractures of the middle third of the clavicle, which account for most clavicular fractures, are treated nonoperatively with a brace, rest and ice. Fractures of the distal third of the clavicle may require open reduction and internal fixation to prevent nonunion. In cases managed nonoperatively, early range of motion and strengthening are recommended to prevent loss of motion at the shoulder.

Forearm

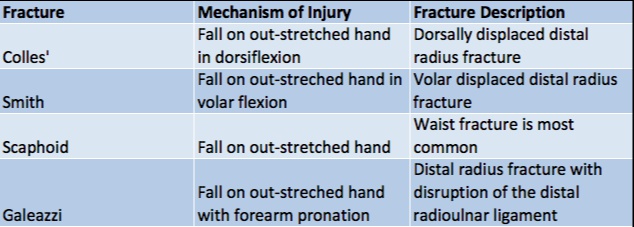

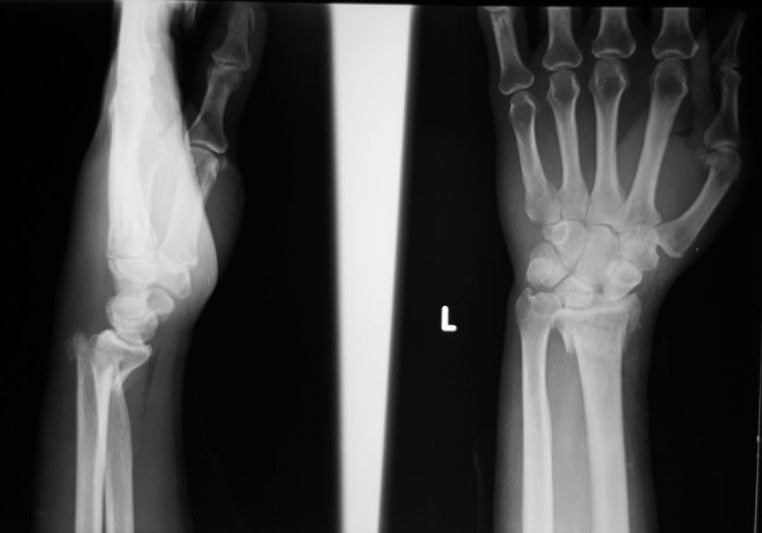

Colles

A dorsally displaced distal radius fracture

.,

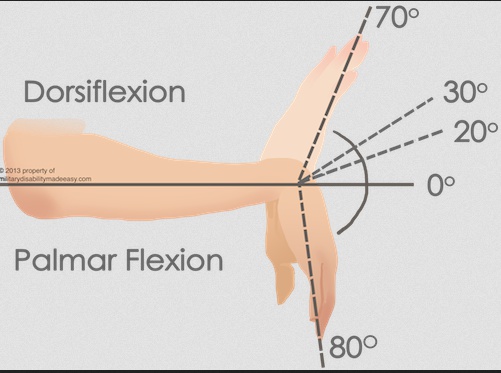

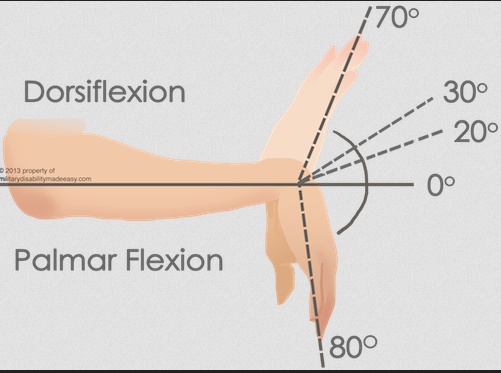

Typically the result of a fall on an out-stretched hand (FOOSH) that is in dorsiflexion. Compare this to a Smith’s fracture, which occurs after a fall on an outstretched hand that is in volar flexion.

A Colles’ fracture presents with tenderness and swelling at the distal forearm with or without visible deformity.

Treatment of a Colles’ fracture consists of:

Closed reduction and casting if stable

Closed reduction with percutaneous pinning if unstable

Open reduction with internal fixation if unstable.

Smith

A volar displaced distal radius fracture.

Typically the result of a fall on an out-stretched hand that is in volar flexion., opposite of the dorsiflexion that produces a Colles’ fracture. They are much less common than a Colles’ fracture.

A Smith’s fracture presents with tenderness and swelling at the distal forearm with or without visible deformity, similar to Colles’ fracture.

Treatment of a Smith’s fracture consists of:

Closed reduction and casting if stable

Closed reduction with percutaneous pinning if unstable

Open reduction with internal fixation if unstable

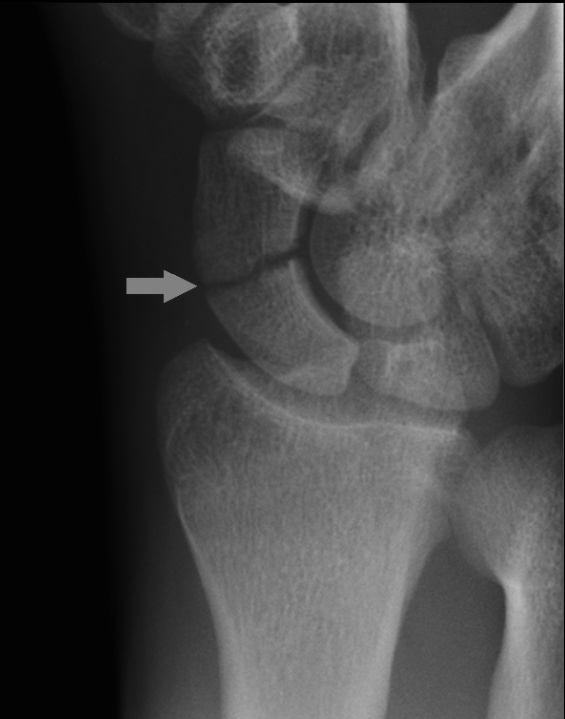

Scaphoid

Scaphoid fractures are the most common fracture amongst all of the carpal bones.

Scaphoid fractures are the result of a fall on an outstretched hand that is radially deviated.

Patients with a scaphoid fracture will present with point tenderness in the anatomical snuff box of the affected hand and local swelling.

Scaphoid fractures are difficult to diagnose because they are not detected on x-ray for up to two weeks after the injury. CT/MRI can be used to confirm diagnosis.

Nondisplaced scaphoid fractures are treated with a thumb spica cast, but displaced fractures require open reduction internal fixation.

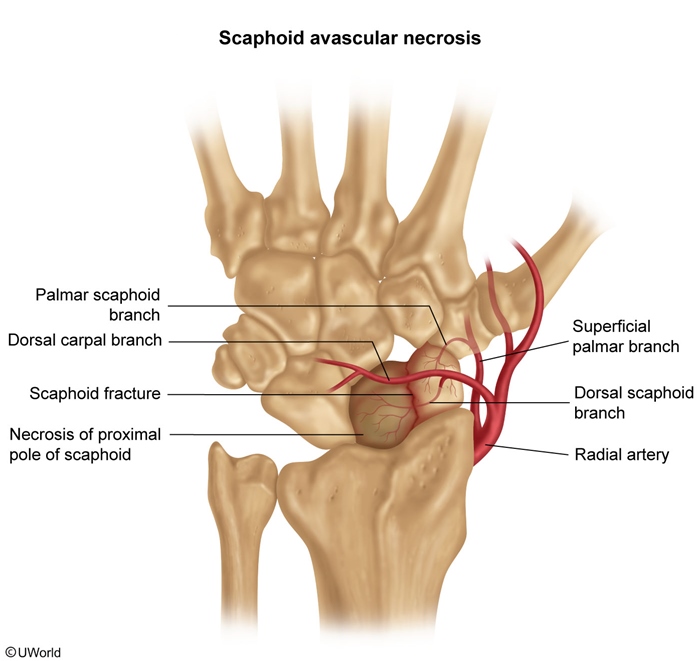

Blood flow in the scaphoid is retrograde, from distal to proximal, so waist (the narrow part of the scaphoid) fractures carry a high risk of avascular necrosis if not properly identified and treated.

case: Physical examination shows mild swelling at the dorsum of the right wrist. There is maximal tenderness proximal to the base of the first metacarpal, and the pain worsens with radial deviation of the wrist. Radiographs of the wrist in multiple views reveal no fracture or dislocation. Which of the following is the most appropriate next step in management of this patient?

Boxer

The most common metacarpal fracture, involving the distal 5th metacarpal (specifically the neck).

.,

A boxer fracture is typically the result of the patient punching a hard object.

A boxer fracture will present with marked swelling around the 5th metacarpal and possible rotational deformity.

Nondisplaced boxer fractures are treated with an ulnar gutter splint, displaced and unstable fractures are treated with surgical pinning or open reduction internal fixation.

Boxer fractures that are actual fight wounds may involve skin penetration by another persons mouth and are considered open until proven otherwise. This “fight-bite” often requires antibiotic treatment as the wound has been exposed to oral flora.

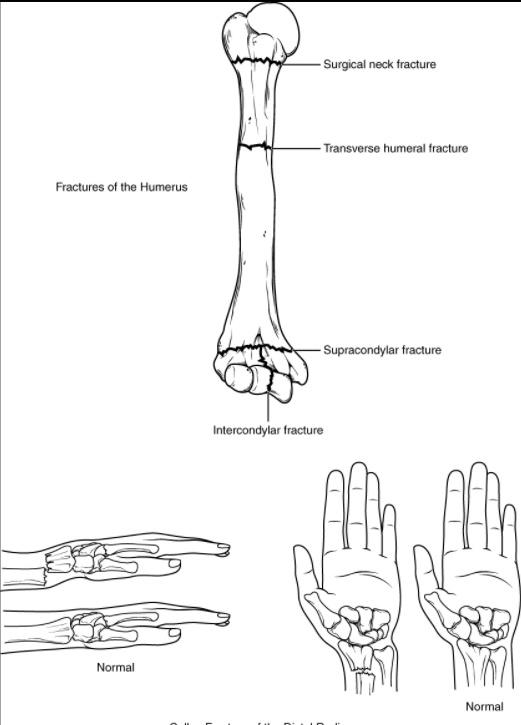

Humerus

Humerus fractures are a common long bone fracture and are generally the result of a direct trauma to the humerus.

A humerus fracture can have a varied presentation, but any displacement is dependent on the relativity of muscle attachment sites to the specific fracture location. This also affects the stability of the fracture. Proximal fractures are more stable due to the distal attachment of shoulder muscles, while the opposite can be said of distal fractures.

A neurovascular examination must be performed in a humeral shaft fracture because of the course of the radial nerve along the posterior aspect of the shaft. Wrist drop or weak thumb abduction suggests radial nerve injury. The deep brachial artery is also at risk of injury.

Stable humeral shaft fractures can be treated with casting, but many active people and those with unstable fractures undergo open reduction with internal fixation.

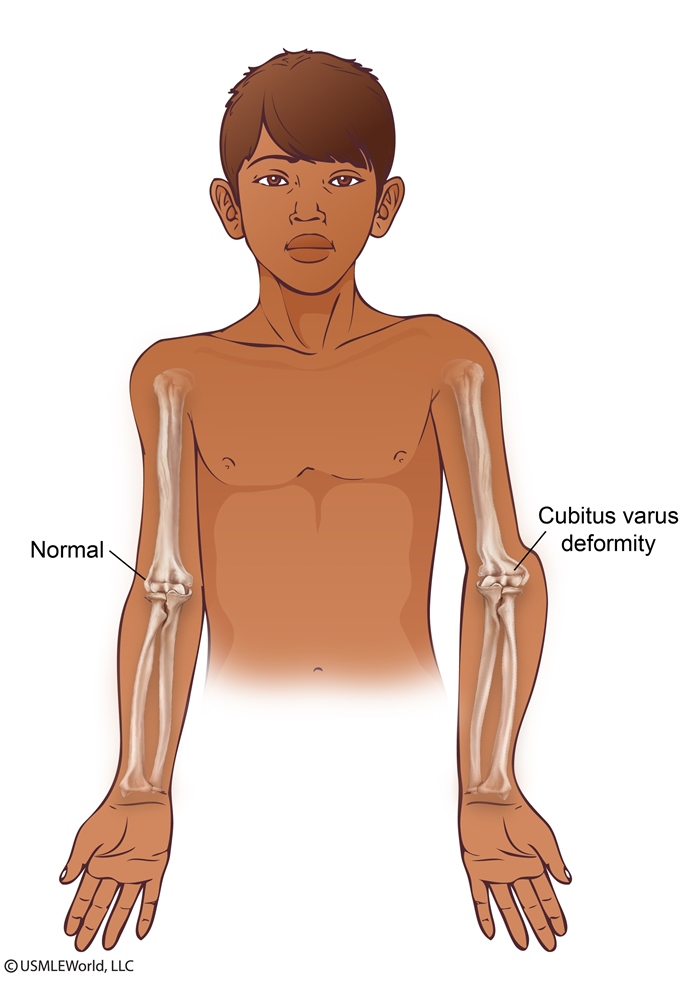

Limb length discrepancy is a complication of proximal humerus and distal forearm fractures. However, the distal physis (growth plate) of the humerus contributes minimally to longitudinal growth due to limited remodeling. As a result, patients with supracondylar fractures of the humerus are at risk for permanent cubitus varus deformity.

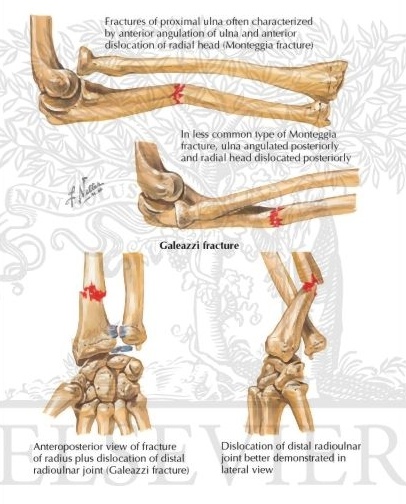

Monteggia

Forearm injury involving a fracture of the proximal third of the ulna with concurrent radial head dislocation, which is more common in children than adults.

.,

Monteggia fractures are typically the result of a fall onto an outstretched hand, or more frequently a trauma. A classic mechanism is called the night-stick fracture, which produces the fracture when a patient guards against a strike using the ulnar side of their forearm.

Patients with a Monteggia fracture will present with pain and swelling at the elbow joint, which may or may not show obvious dislocation.

Most Monteggia fractures in children are treated with a cast, but most adults are treated surgically.

A major complication of Monteggia fractures is compartment syndrome, which is a rise in intracompartmental pressure that impedes blood flow.

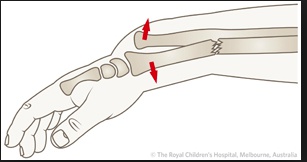

Galeazzi

Forearm injury involving fracture of the distal third of the radial shaft with concurrent disruption of the distal radioulnar ligament.

.,

Galeazzi fractures usually occur due to direct trauma or a fall onto an outstretched, pronated forearm.

A Galeazzi fracture presents with pain, swelling, and visual deformity of the distal forearm.

Because of the instability of a Galeazzi fracture, they are treated surgically to reduce the radius and with casting to keep the distal radioulnar joint reduced.

As with Monteggia fractures, the traumatic nature of this fracture puts patients at risk of compartment syndrome.

Lower Extremity Fractures

Hip

Hip fractures include fractures of the femoral head or neck, but femoral neck fractures are much more common.

Fractured hips are very common amongst elderly patients during a fall because of decreased bone strength, but they can also occur in younger patients due to motor vehicle accidents or other trauma.

In a hip fracture, the patient’s leg is shortened and externally rotated.

Treatment of hip fractures is generally open reduction internal fixation as closed reductions do not hold. Older patients should be anticoagulated for DVT prophylaxis.

Femoral neck fractures are high risk for avascular necrosis, as well as DVT due to prolonged immobilization.

Hip Dislocations

90% of hip dislocations occur in the posterior direction and are usually associated with a high-energy athletic event or trauma (e.g. motor vehicle accident).

Posterior hip dislocations present with legs that appear shortened, internally rotated, and adducted.

Anterior hip dislocations can be either superior or inferior. Superior hip dislocations present with a hip that is extended and externally rotated. Inferior hip dislocations present with a hip that is flexed and externally rotated.

Many hip dislocations are associated with acetabular fractures and less often with fractures of the femoral head.

Plain film radiography should be used in the initial assessment of suspected pelvic and hip injury.

MRI is used to determine extent of ligamentous injury and is the gold standard imaging study in ruling out avascular necrosis of the femoral head. It is recommended that patients receive MRI 3-4 weeks post reduction to rule out any complications from avascular necrosis.

Isolated hip dislocation can be life-threatening and require emergent reduction. A closed reduction should be performed as soon as possible to decrease the risk of avascular necrosis and sciatic nerve damage.

Long term complications of hip dislocation include:

Avascular necrosis

Neurovascular compromise

Posttraumatic arthritis

Recurrent dislocation

Pelvic

Pelvic fracture generally refers to a fracture of the acetabulum that occurs due to high-energy trauma in younger patients or a fall in older patients.

Patients with a pelvic fracture are unable to bear weight and may have a malrotated lower extremity.

A patient with major pelvic trauma who is hemodynamically unstable should receive a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST).

If positive, the patient should be taken to the OR to address abdominal hemorrhage. Pelvic arteriography can be used if needed.

If negative, the patient should receive a diagnostic peritoneal aspirate. If positive, treat like positive FAST. If negative, extraabdominal hemorrhage should be controlled with pelvic stabilization and preperitoneal packing or pelvic arteriography.

A patient with major pelvic trauma who is hemodynamically stable should receive an abdominal CT scan.

If there are signs of active pelvic bleeding, pelvic arteriography should be performed. If there are no signs of active pelvic bleeding, the patient should be observed with serial examination.

Femur

Femur fractures involve the shaft of the femur and are considered an orthopedic emergency.

Femoral shaft fractures are generally the result of a high-energy trauma.

Femoral shaft fractures are treated surgically, which can include intramedullary nailing or open reduction internal fixation with plating.

These patients are at risk for significant blood loss,compartment syndrome, and fat embolism.

Tibia

Tibial shaft fractures are the most common lower extremity long bone fracture and typically involve a concurrent fibular fracture.

These fractures commonly occur due to high-energy trauma.

Patients with a tibial shaft fracture present with pain, swelling, and inability to bear weight.

Treatment of a tibial shaft fracture includes casting for nondisplaced fractures and intramedullary nailing if displaced or unstable.

Tibial shaft fractures are at an increased risk for developing compartment syndrome, which requires a fasciotomy to salvage the limb.

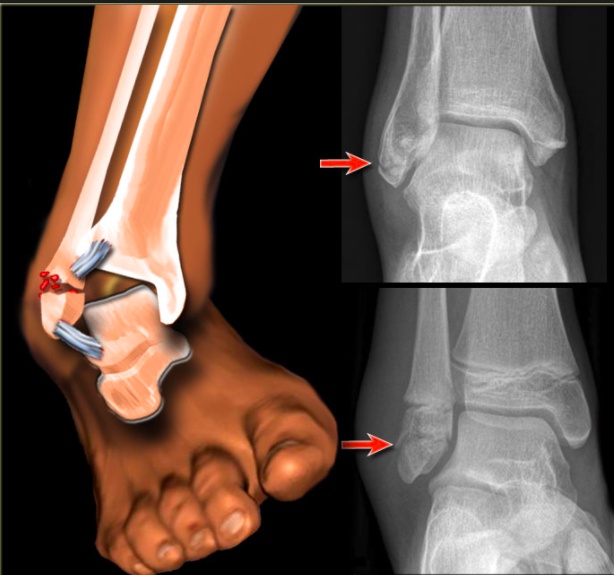

Ankle

Ankle fractures include fractures of the medial, lateral, and/or posterior malleoli.

Medial malleolus fractures are generally the result of an eversion injury whereas lateral malleolus fractures are the result of an inversion injury.

lateral malleolus:

medial malleolus:

These fractures commonly occur in athletes and as a result of trauma.

Non displaced ankle fractures are treated with a cast, but displaced or unstable fractures require open reduction internal fixation.

Stress Fractures

usually in athletes/military recruits

Stress fracture

Risk factors

Repetitive activities (eg, running, gymnastics). Abrupt increase in physical activity. Inadequate calcium & vitamin D intake. Decreased caloric intake. Female athlete triad: low caloric intake, hypomenorrhea/amenorrhea, low bone density

Clinicalpresentation

Insidious onset of localized pain. Point tenderness at fracture site. Possible negative x-ray in the first 6 weeks but may reveal periosteal reaction at the site of the fracture.

Management

Reduced weight bearing for 4-6 weeks and simple analgesics (acetaminophen). Do not use NSAIDS as it can delay healing. Referral to orthopedic surgeon for fracture at high risk for malunion (eg, anterior tibial cortex, 5th metatarsal). Pts with continued pain can be given wide, hard-sole podiatric shoe.

Stress fractures of the fifth metatarsal shaft are at increased risk for nonunion and are usually managed with casting or internal fixation. However, stress fractures of the middle (ie, second, third, and fourth) metatarsals usually heal well and do not require casting or surgery unless there is severe pain, displacement, or other complicating factors.

Shin Splints

Medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splints) causes anterior leg pain resembling that of a stress fracture. It is usually seen in casual runners and is characterized by a diffuse area of tenderness (not point tenderness, as seen in this patient). Shin splints are more common in overweight than underweight individuals.

Hip Pain

The differential diagnosis for unilateral hip pain in a middle-aged adult is broad, and includes infection, trauma, arthritis, bursitis, and radiculopathy. This particular patient’s presentation is most consistent with trochanteric bursitis. Trochanteric bursitis is inflammation of the bursa surrounding the insertion of the gluteus medius onto the femur’s greater trochanter. Excessive frictional forces secondary to overuse, trauma, joint crystals, or infection are responsible. Patients with this condition complain of hip pain when pressure is applied (as when sleeping) and with external rotation or resisted abduction.

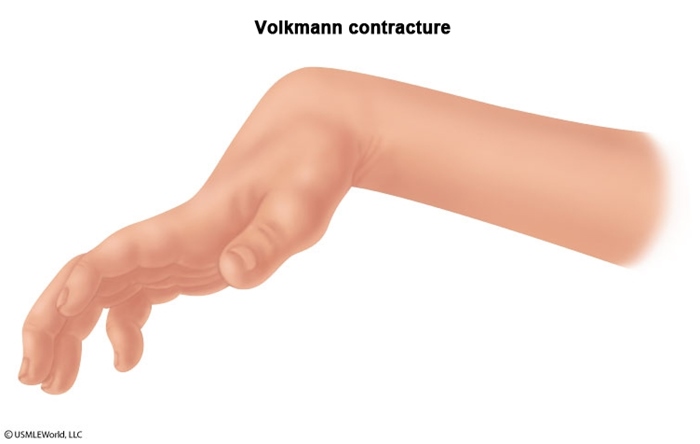

Compartment Syndrome

Compartment syndrome is a condition where increased pressure in a confined space compromises circulation within that space, resulting in ischemia.

Post-ischemic compartment syndrome results from the reintroduction of oxygenated blood into damaged tissues, which generates oxygen free radicals that interact with cell membranes to increase capillary permeability.

Post-ischemic compartment syndrome results from a biphasic ischemia-reperfusion injury.

Incidence of limb compartment syndrome varies by location with closed tibial fractures being the most common.

Compartment syndrome is broadly categorized as either limb or abdominal compartment syndrome.

Abdominal

Abdominal compartment syndrome results from increased intra-abdominal pressure, leading to cardiovascular, renal, and respiratory dysfunction. It most often follows a surgical procedure, but can result from other causes (trauma, pancreatitis, infection, etc).

Abdominal compartment syndrome most often results status post surgery or trauma.

Limb

Limb compartment syndrome starts with a traumatic or hemorrhagic event that causes edema. The edema compresses microcirculation, which leads to muscle and nerve ischemia. The ischemic damage results in the release of osmotically active substances, increased edema, and worsening ischemia.

case: A 29-year-old woman comes to the emergency department after spilling hot coffee on her left forearm. Medications include a daily oral contraceptive, and the patient has no other medical issues. Evaluation shows a full-thickness burn, and she is discharged with analgesics, topical antibiotics, and wound care instructions. Three days later, the patient returns due to worsening pain and swelling of the left hand. She describes the pain in her hand as severe and aching. Repeat examination shows previous burn injury healing with a circumferential eschar formation. Her left hand is tense and tender. Which of the following is the most likely cause of this patient's condition?

Symptoms

Compartment syndrome presentations vary, but they chiefly rely on whether or not the patient is conscious or intoxicated.

Conscious patients will experience the “6 P’s”:

Pain that is severe and grossly out of proportion with the injury (pain with passive movement)

Tissue tension, followed by ischemia

Paresthesia (tingling, pins and needles) (sensory nerve ischemia)

Paresis (no movement) (later)

Pallor of the overlying skin (arterial occlusion, rare)

Poikilothermia (can't regulate temperature)

Pulselessness (late)

Intoxicated patients have a blunted pain response.

Abdominal compartment syndrome is often unapparent because patients are frequently on ventilator support in the ICU.

Ischemic pain is different from the initial traumatic pain.

The eschar that results from a circumferential, full-thickness (third degree) burn often leads to constriction of venous and lymphatic drainage, fluid accumulation, and resulting distal ACS.

case: A 29-year-old woman comes to the emergency department after spilling hot coffee on her left forearm. Medications include a daily oral contraceptive, and the patient has no other medical issues. Evaluation shows a full-thickness burn, and she is discharged with analgesics, topical antibiotics, and wound care instructions. Three days later, the patient returns due to worsening pain and swelling of the left hand. She describes the pain in her hand as severe and aching. Repeat examination shows previous burn injury healing with a circumferential eschar formation. Her left hand is tense and tender. Which of the following is the most likely cause of this patient's condition?

Like CS, DVT may also present with increasing pain and swelling, but symptoms are more insidious in onset and less severe. The presence of neurologic symptoms makes CS more likely, especially in a patient who is predisposed.

Recurrent embolism may produce features similar to CS (severe pain, paresthesias). Embolic occlusion can be differentiated from CS by absent pulses, pallor of the affected limb, and lack of local swelling.

Diagnosis

Compartment syndrome diagnosis differs between limb and abdominal compartments.

Limb compartment syndrome is diagnosed through a history of trauma/burn, limb intra-compartment pressure measurement, and markedly elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK) from the severe muscle damage or ischemia.

Abdominal compartment syndrome is diagnosed through clinical signs (e.g. tense abdomen, cardiorespiratory compromise without hypovolemia, or oligouria/anuria) and increased intra-abdominal pressure measured by transurethral bladder pressure.

Intra-abdominal pressure may be elevated in critically ill patients with recent abdominal surgery, body position changes, sepsis, organ failure, or mechanical ventilation.

Treatment

Treating compartment syndrome involves relieving the increased compartment pressure to maintain perfusion.

Limb compartment syndrome can be relieved by fasciotomy and hyperbaric oxygen.

Abdominal compartment syndrome can be eased by fluid resuscitation to help maintain abdominal perfusion. Other strategies include changing body position, evacuation of intra-abdominal contents, and neuromuscular blockade. Surgical decompression via laparotomy is indicated when other treatments fail.

Complications

Limb compartment syndrome local complications include:

Infection

Contractures (including Volkmann)

Deformity

Amputation

Limb compartment syndrome systemic complications include:

Acidosis

Hyperkalemia

Myoglobinuria

Acute renal failure

Shock

Abdominal compartment syndrome can cause multisystem failure and death.

Meniscus Tears

Meniscus tears can occur in both the lateral and/or medial menisci of the knee and typically result from degeneration or forceful trauma.

Meniscal tears related to degeneration are more common in the medial meniscus, whereas in acute sports injuries the lateral meniscus is more commonly injured.

The clinical presentation of meniscal tears includes pain localizing to the side of the tear with the addition of locking and clicking with use of the knee.

A lateral meniscus tear is part of the "unhappy triad," a sports related injury. The “unhappy triad” is usually caused by a direct blow to lateral knee and consists of tears to the:

Lateral meniscus

Medial collateral ligament

Anterior cruciate ligament

O'Donoghue, in the 1950's, had originally described the combination to include the medial and not lateral meniscus; however, medial meniscus involvement was later found to be less common than lateral meniscus involvement.

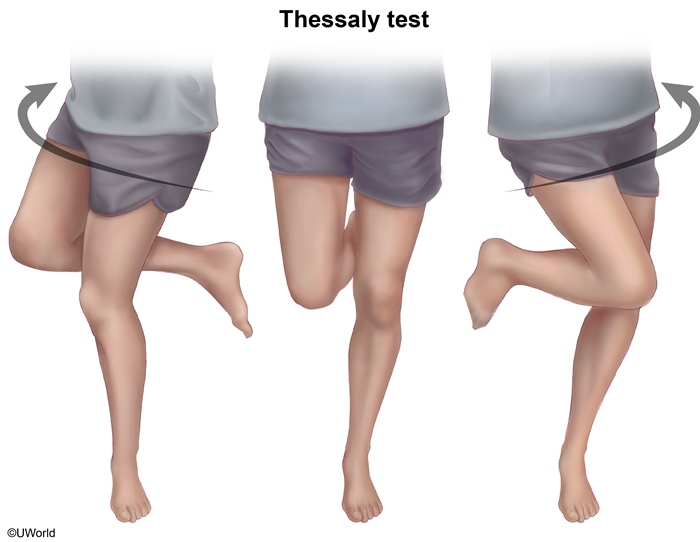

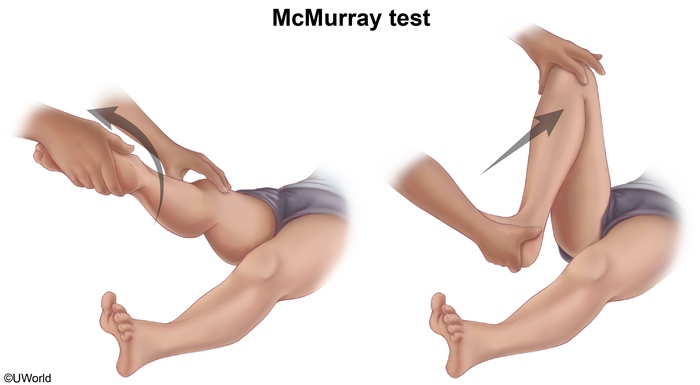

Physical exam findings in meniscal tears include joint line tenderness and a positive McMurray’s test, which is where extending the knee from a flexed position with varus or valgus strain produces pain and/or a palpable pop or click.

swelling after several days

sensitivity of provocative tests vary and may be negative. Use MRI to confirm

MRI is used to detect or confirm the presence of a meniscal tear.

Conservative treatment for meniscal tears includes NSAIDs, physical therapy, and knee arthroscopy. NSAIDs and physical therapy are indicated as first line in degenerative meniscal tears.

Knee arthroscopy provides the greatest patient satisfaction, but it is associated with a slightly accelerated development of osteoarthritis.

The main complication with meniscal tears is the accelerated development of osteoarthritis when patients receive arthroscopic treatment.

Joint

Septic Arthritis

Septic arthritis is an infection of the synovial joint space.

Septic arthritis can occur through hematogenous spread, local extension, or direct inoculation.

S. aureus is the most common culprit in septic arthritis, accounting for more than 50% of cases.

In young, sexually active patients with septic arthritis who are otherwise healthy, consider N. gonorrhoeae.

Like osteomyelitis, consider Salmonella in patients with sickle cell disease and P. aeruginosa in IV drug users and diabetics in cases of septic arthritis.

Most cases of septic arthritis involve a bacterial infection, but fungal and candida infections can be found in immunocompromised patients.

The clinical presentation of septic arthritis includes:

Pain in the affected joint, most commonly the knee

Fever

Pain during passive range of motion

Physical exam findings in septic arthritis include a warm, red, and tender joint with possible skin lesions over the affected area.

Serum findings in septic arthritis include a WBC count > 10,000, ESR > 30, and CRP > 5.

Joint aspirate is the gold standard in septic arthritis and shows a WBC count > 50,000, which is diagnostic for septic arthritis. Joint aspirate also shows a high neutrophil count and low glucose.

Ultrasound and MRI can help confirm joint effusion in septic arthritis.

Treatment of septic arthritis involves surgical irrigation and drainage of the affected joint.

For S. aureus septic arthritis, add penicillinase-resistant penicillin, such as nafcillin, oxacillin, and dicloxacillin.

For gram negative bacteria septic arthritis, add a cephalosporin (ceftriaxone or cefepime), or a fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin).

For N. gonorrhoeae septic arthritis, use ceftriaxone and either azithromycin or doxycycline because of the potential for coinfection with Chlamydia. Surgical irrigation and drainage is usually not necessary in cases of N. gonorrhoeae infection.

Monitoring CRP is the best measure of treatment efficacy in cases of septic arthritis.

Prosthetic Joint Infection

Prosthetic joint infection

Early onset

Delayed onset

Late onset

Time to onset after surgery

<3 months

3-12 months

>12 months

Presentation

Acute pain. Wound infection or breakdown. Fever

Chronic joint pain. Implant loosening. Sinus tract formation

Acute symptoms in previously asymptomatic joint. Recent infection at distant site

Most common organisms

Staphylococcus aureus. Gram-negative rods. Anaerobes

Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Propionibacterium species. Enterococci

Staphylococcus aureus. Gram-negative rods. Beta-hemolytic streptococci

This patient has subacute pain in his prosthetic knee 6 months after arthroplasty. The synovial fluid analysis shows a mildly elevated leukocyte count with a predominance of neutrophils. This is consistent with an inflammatory process, most likely a prosthetic joint infection (PJI). The leukocyte count in the synovial fluid in PJI is usually elevated to >1000/mm3 but is often lower than in septic native joints (usually >50,000/mm3).

PJI can be acquired by perioperative contamination of the joint or by extension from an overlying wound infection:

Infections due to virulent organisms (eg, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) typically present within the first 3 months after surgery (early onset infection) with acute pain, fever, leukocytosis, and overt local signs of infection (eg, erythema, purulent drainage), not seen in this patient.

Infections due to less virulent organisms (eg, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Propionibacterium species), as in this patient, are likely to have a delayed onset (3-12 months) and present with chronic pain, implant loosening, gait impairment, or sinus tract formation. Fever and leukocytosis are usually absent. Staphylococcus epidermidis is a coagulase-negative staphylococcus commonly implicated in delayed-onset PJI.

Late-onset infections presenting >12 months after surgery are unlikely to have been acquired perioperatively and are usually due to hematogenous spread of a distant infection (eg, urinary tract infection).

Fat Embolism

Fat embolism syndrome

Etiology

Fracture of marrow-containing bone (eg, femur). Orthopedic surgery. Pancreatitis

Clinical presentation

24-72 hours following inciting event. Clinical triad: Respiratory distress, Neurologic dysfunction (eg, confusion), Petechial rash

Diagnosis

Based on clinical presentation

Prevention & treatment

Early immobilization of fracture. Supportive care (eg, mechanical ventilation)

This patient most likely has fat embolism syndrome (FES). The mechanism of FES is not completely understood, but it is postulated that fat enters the venous circulation following an inciting event (eg, femur fracture) and causes mechanical disruption of capillary blood flow (fat microemboli may be small enough to pass through the pulmonary circulation to the systemic circulation) or leads to a systemic inflammatory response through the production of toxic intermediaries. Patients classically have a triad of severe respiratory distress (eg, hypoxemia, dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia), which can mimic acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS); neurologic dysfunction (eg, confusion, visual field defects); and a petechial rash (present in up to half of cases). Low-grade fever and subconjunctival hemorrhage may also be present. Chest x-ray is typically unremarkable at the time of symptom onset but reveals bilateral pulmonary infiltrates within 24-48 hours.

The diagnosis of FES is based on compatible clinical presentation. Treatment is supportive; approximately half of patients with FES due to long bone fracture require mechanical ventilation. Death can occur, but the majority of patients make a full recovery.

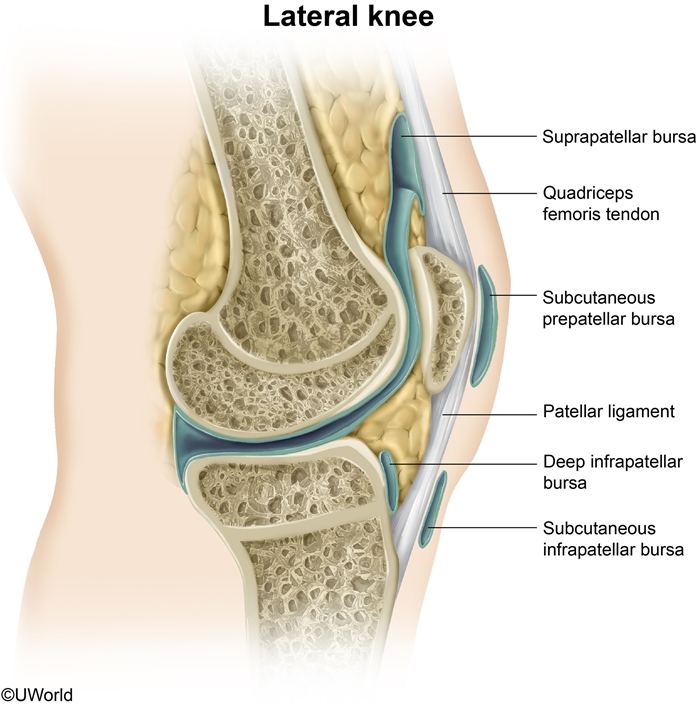

Bursitis

A bursa is a synovial sac that alleviates friction at bony prominences and ligamentous attachments. Bursae are vulnerable to acute injury or chronic repetitive pressure and may become inflamed due to infection (septic bursitis), crystalline arthropathy (eg, gout), or autoimmune conditions (eg, rheumatoid arthritis). Because bursae are located in exposed positions, the pain and tenderness of bursitis may be exquisite. Other features may include swelling and erythema, particularly with more superficial bursae. Active range of motion is often decreased or painful, but passive motion is usually normal as it causes less pressure on the inflamed bursa.

This patient with acute pain and localized tenderness has prepatellar bursitis, sometimes called "housemaid's knee." Prepatellar bursitis is common in occupations requiring repetitive kneeling, such as concrete work, carpet laying, and plumbing. While bursitis in other locations is generally noninfectious, acute prepatellar bursitis is very commonly due toStaphylococcus aureus, which can infect the bursa via penetrating trauma, repetitive friction, or extension from local cellulitis. The diagnosis should be confirmed with aspiration of bursal fluid for cell count and Gram stain. If Gram stain and culture are negative, patients may be managed with activity modification and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Otherwise, patients are treated with drainage and systemic antibiotics.

(Choice A) Bursal fluid in prepatellar bursitis should be examined for urate crystals. However, gout is a less common cause of bursitis, and this patient has no history of gout in more common locations (eg, 1st metatarsophalangeal joint).

(Choice B) Fractures of the patella present with acute swelling, tenderness, and inability to extend the knee. They are usually caused by a direct blow or a sudden force under load (eg, fall from height).

(Choice C) Infectious (septic) arthritis typically presents with acute pain, joint effusion, and fever. The swelling will involve the joint space proper rather than the anterior tissues, and patients will have pain with active and passive range of motion.

(Choice D) Patellar tendinitis causes episodic pain and tenderness at the inferior patella and patellar tendon. It is usually seen in athletes in jumping sports or in occupations with repetitive forceful knee extension.

(Choice E) Patellofemoral pain syndrome causes chronic anterior knee pain and is most common in women. It presents with peripatellar pain worsened by activity or prolonged sitting.

Shoulder Pain

Common causes of shoulder pain

Rotator cuff impingement or tendinopathy

Pain with abduction, external rotationSubacromial tendernessNormal range of motion with positiveimpingement tests (eg, Neer, Hawkins)

Rotator cuff tear

Similar to rotator cuff tendinopathyWeakness with external rotationAge >40

Adhesive capsulitis(frozen shoulder)

Decreased passive & active range of motionMore stiffness than pain

Biceps tendinopathy/rupture

Anterior shoulder painPain with lifting, carrying, or overhead reachingWeakness less common

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis

Uncommon & usually caused by traumaGradual onset of anterior or deep shoulder painDecreased active & passive abduction & external rotation

This patient with subacute shoulder pain on abduction most likely hasrotator cuff tendinopathy (RCT). RCT results from repetitive activity above shoulder height (eg, painting ceilings) and is most common in middle-aged and older individuals. Chronic tensile loading and compression by surrounding structures can lead to microtears in the rotator cuff tendons (especially supraspinatus), fibrosis, and inflammatory calcification. In addition to the rotator cuff itself, pain may also emanate from the subacromial bursa and the tendon of the long head of the biceps.

On flexion or abduction of the humerus, the space between the humeral head and acromion is reduced, causing pressure on the supraspinatus tendon and subacromial bursa. Impingement syndrome, a characteristic of RCT, refers to compression of these soft tissue structures. Impingement can be demonstrated with the Neer test: With the patient's shoulder internally rotated and forearm pronated, the examiner stabilizes the scapula and flexes the humerus. Reproduction of the pain is considered a positive test.

Untreated, chronic RCT can increase the risk for rotator cuff tear. Patients with a tear typically present with weakness of abduction following a fall or other minor trauma (Choice B).

(Choice A) Adhesive capsulitis ("frozen shoulder") is characterized by fibrosis and contracture of the glenohumeral joint capsule. It causes persistent pain along with decreased range of motion in multiple planes and can be idiopathic or due to underlying shoulder pathology (eg, chronic RCT).

(Choices C and E) Pain can be referred to the shoulder from cervical nerve root impingement (cervical radiculopathy), diaphragmatic irritation (eg, intrathoracic tumor), myocardial ischemia, or hepatobiliary disease (eg, gallstones). Cervical radiculopathy typically presents with pain and paresthesias of the neck and arm along with upper extremity weakness. However, referred pain would not cause impingement signs and would not be exacerbated by shoulder movement.

(Choice F) Rupture of the tendon of the long head of the biceps may occasionally be seen with overuse in older patients. It typically causes sudden onset of pain, often with an audible pop and visible bulge.

Last updated