06 Trauma

Abdominal

Causes

Abdominal trauma can be caused by a variety of mechanisms including penetrating trauma (e.g. from a stab wound or gunshot wound) or blunt trauma (e.g. from a motor vehicle accident).

Rib fractures may be a cause or complication of these injuries.

Symptoms

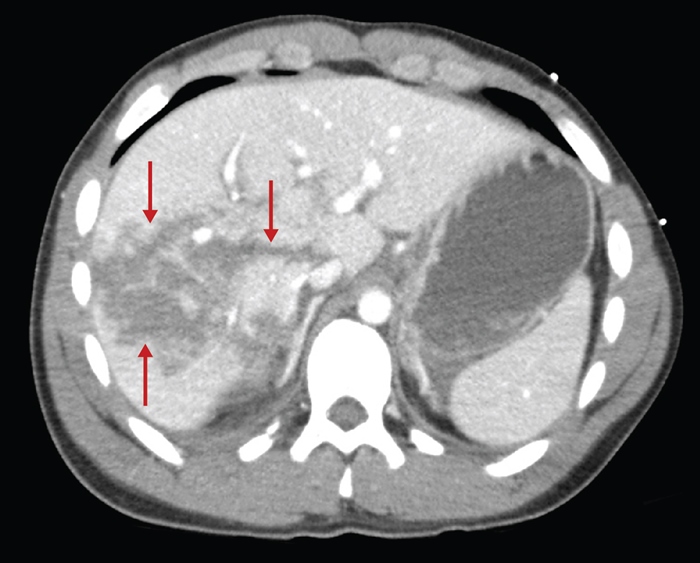

The liver and spleen are at high-risk for injury during blunt abdominal trauma.

Clinical presentation may include:

Abdominal distension

Tenderness or fullness on palpation

Guarding

Bowel sounds in the thorax

Crepitation of lower thoracic cage

Duodenal and pancreatic injuries due to BAT are relatively uncommon but may present with nausea, vomiting, inability to tolerate oral intake, progressive abdominal pain, and sepsis. Patients with duodenal hematomas may also have evidence of small-bowel obstructions. However, neither duodenal hematomas nor pancreatic transections are commonly associated with free intraperitoneal fluid.

Duodenal hematomas (DHs) most commonly occur following blunt abdominal trauma (BAT). They are more commonly seen in children due to a number of anatomic differences, including thinner abdominal wall musculature, less abdominal adipose tissue, and more pliable ribs (which absorb less force than the stiffer ribs of adults). DH commonly occurs when a blunt force rapidly compresses the duodenum against the vertebral column. Following trauma, blood collects between the submucosal and muscular layers of the duodenum causing partial or complete obstruction.

Patients with DH due to BAT may initially have only symptoms of abdominal wall trauma, which may improve before subsequent clinical deterioration as the DH expands. Patients classically present 24-36 hours after the initial event with epigastric pain and vomiting due to failure to pass gastric contents beyond the obstructing hematoma. Diagnosis is confirmed with CT imaging of the abdomen.

Most DHs will resolve in 1-2 weeks. Management involves decompression by nasogastric tube and, in many patients, parenteral nutrition. Surgery or percutaneous drainage may be considered to evacuate the hematoma if nonoperative management fails.

Management

The goal of the primary survey of a patient that has sustained abdominal trauma is to identify and treat life-threatening injuries. This is dictated by the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol, and includes:

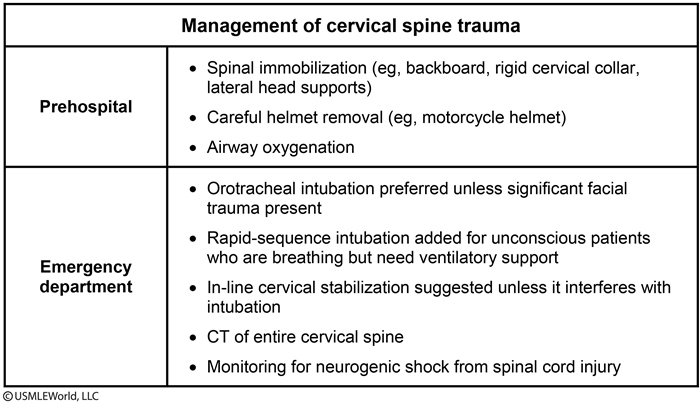

Airway maintenance, with cervical spine precautions

Breathing

Circulation

Disability

Exposure

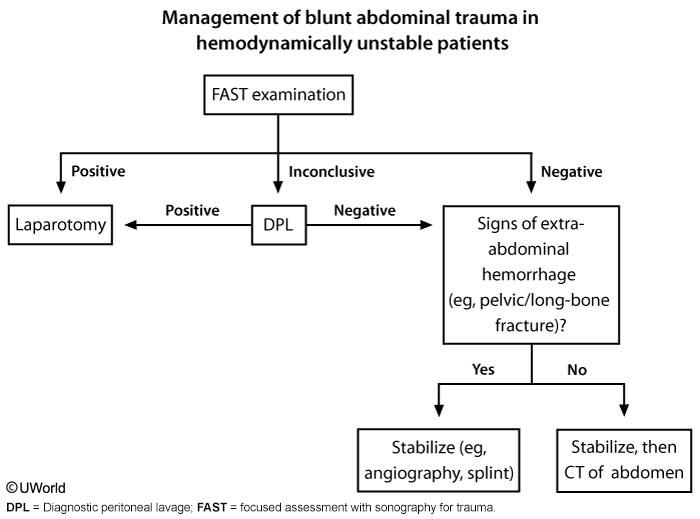

Blunt Trauma

Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) scan can be used to evaluate potential areas of blood collection within the peritoneum. It should be the first step in alert and hemodynamically stable (eg, systolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg) patients. If FAST is limited or equivocal, a diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) can be done to evaluate for hemoperitoneum, but only for blunt and not penetrating trauma. Hemodynamically unstable patients with a positive finding on either DPL or FAST should undergo exploratory laparotomy. Hemodynamically stable but altered should undergo CT.

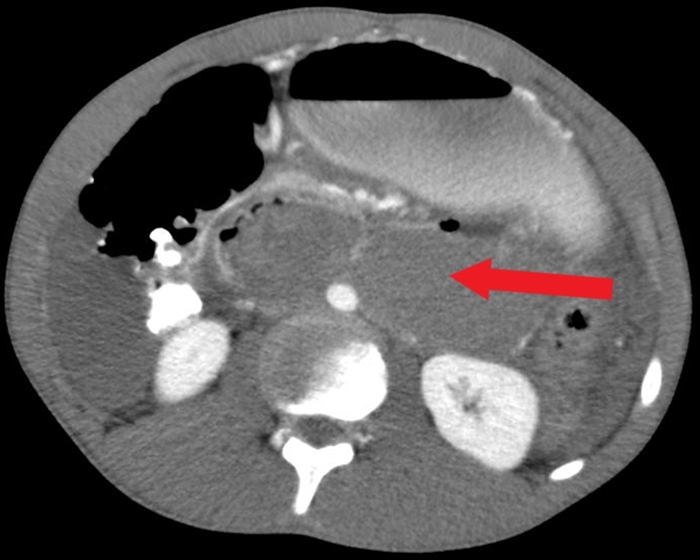

CT scan of the abdomen gives detailed information about the pathology and source of hemorrhage (if present). It may also assist in planning of operative intervention.

Penetrating Trauma

Although this patient has no evidence of intraperitoneal fluid on abdominal ultrasound, he has rebound tenderness, which is associated with a greatly increased likelihood of intraabdominal organ injury (eg, intestines, great vessels, spleen, diaphragm). The presence of any of the following suggests significant injury and is an indication for urgent exploratory laparotomy:

Hemodynamic instability

Peritonitis (rebound tenderness, guarding)

Evisceration (ie, externally exposed intestines)

Blood from a nasogastric tube or on rectal examination

Patients without indications for urgent laparotomy should undergo further evaluation, including local exploration of the wound and an extended ultrasound examination (eg, extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma [eFAST], which evaluates for pneumothorax and hemothorax in addition to intraperitoneal injuries).

Irritation of the diaphragm (e.g. due to splenic rupture) may cause referred pain to the shoulder area, typically the left shoulder. This is known as Kehr’s sign.

Unstable patients with peritoneal signs (e.g. pain, rebound tenderness, guarding) or evisceration status post trauma warrant immediate surgery.

Patients should be kept on hemodynamic monitoring and followed clinically with serial abdominal exams.

Complications

Complications of abdominal trauma to the liver and spleen may include:

Hypovolemic shock

Infection

Diaphragmatic rupture

Hematoma rupture

Abscess formation

Bowel obstruction or ileus

Abdominal compartment syndrome

Airway

In trauma resuscitation, always secure the airway first.

If the patient is speaking in a normal tone of voice, s/he has a patent airway. If emphysema in the neck or an expanding neck hematoma is noted, the patient has a threatened airway, requiring airway management.

Intubation is indicated in all patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score equal to or less than 8.

Neck hyperextension in patients with possible cervical spine injury should be avoided; in-line stabilization and/or fiberoptic intubation should be used when intubating.

The three main ways to secure an airway are:

Cricothyroidotomy

Orotracheal intubation

Percutaneous tracheostomy

In the field without access to orotracheal intubation, cricothyroidotomy is most commonly used.

In the emergency department, use rapid sequence induction and orotracheal intubation. Avoid nasal intubation if the patient has facial fractures.

In a patient with extensive maxillofacial injuries (preventing passage of an endotracheal tube), perform cricothyroidotomy or percutaneous tracheostomy.

Nasotracheal intubation is a blind procedure that is contraindicated in apneic/hypopneic patients. It is also contraindicated if the patient has a basilar skull fracture as such fractures are associated with a risk of cribriform plate disruption, which could lead to inadvertent intracranial passage of the tube.

Due to the risk of carbon dioxide retention, needle cricothyroidotomy is not ideal in patients with head injury who might require hyperventilation to prevent or treat intracranial hypertension. However, it is preferred to surgical cricothyroidotomy in children age <12 as it is easier to perform anatomically.

Breathing is assessed by the movement of air:

Breath sounds in both right and left lung fields

Normal pulse oximetry

Head Injuries

Every patient who sustains head trauma and becomes unconscious for any period of time requires a head CT scan.

Hospitalization

Patients who sustain head trauma and become unconscious for any period of time do not need to be hospitalized if the following conditions are met:

There is no intracranial bleeding on CT scan.

The patient is neurologically intact.

The patient has someone who will check on him/her frequently for 24 hours to ensure the patient is not becoming comatose and to bring the patient back to the ER if signs and symptoms of traumatic brain injury (e.g. headache, vomiting, dizziness, confusion) persist or worsen.

Linear Fractures

Generally, the rules for linear skull fractures are the following:

If the fracture is closed (no overlying wound), it requires no direct treatment.

If the fracture is open, the wound needs to be closed.

If the fracture is comminuted and/or depressed, it must be surgically repaired in the OR.

Skull Base Fractures

Signs of skull base fractures are:

Periorbital ecchymoses (i.e. raccoon eyes)

Rhinorrhea (CSF dripping from nose)

Otorrhea (CSF leaking from ears)

Ecchymosis behind the ear (i.e. Battle’s sign)

If skull base fracture is suspected in a conscious patient, a CT of the c-spine is indicated to check for cervical spine fractures.

If skull base fracture is suspected in a patient who was unconscious, a CT of the head including the c-spine is indicated to check for intracranial bleeding and cervical spine fractures.

Epidural

Epidural hematoma is usually caused by tearing of the middle meningeal artery due to head trauma. Classically, the patient will initially lose consciousness from the initial trauma then have a "lucid interval" followed by rapid neurologic deterioration. The clinical course is commonly described as "talk and die."

Head CT scan provides the most definitive diagnosis of an epidural hematoma. It will classically show a biconvex, lens-shaped hematoma.

Once diagnosed by head CT scan, the treatment for epidural hematoma is rapid craniotomy to evacuate the hematoma. Generally, a good outcome is expected if treated promptly.

If not treated with craniotomy, the expanding hematoma can lead to compression of CN3 resulting in an ipsilateral fixed dilated pupil and a subfalcine herniation with compression of the cerebral cortex and brainstem resulting in contralateral hemiparesis with decerebrate posturing (i.e. shoulder adducted, elbow extended, forearm pronated and fingers flexed).

Subdural

Acute subdural hematoma is usually caused by tearing of the bridging veins in the subdural space. Classically, there is more severe trauma than that associated with an acute epidural hematoma. A patient may be immediately knocked unconscious and never fully regain consciousness due to the severity of the initial injury. Mass effects of the acute subdural hematoma may cause a midline shift.

Chronic subdural hematomas are most commonly seen in alcoholics and the elderly. These patients have significant brain atrophy causing an increased susceptibility to bridging vein tearing.

Head CT scan provides the most rapid and definitive diagnosis of acute subdural hematoma. It will classically show a semilunar crescent-shaped hematoma.

Once diagnosed by head CT scan, the treatment for an acute subdural hematoma depends on whether there is an midline shift.

If midline brain structures are displaced by the hematoma, craniotomy may help.

If midline brain structures are not deviated, craniotomy will not help and the patient should be managed medically to prevent or minimize subsequent development of increased ICP (intracranial pressure).

Increased ICP is managed in the following ways:

ICP monitoring

Elevate head of bed

Hyperventilate

Avoid fluid overload with gentle diuresis with mannitol or furosemide

Once diagnosed by head CT scan, craniotomy may result in dramatic improvement of a chronic subdural hematoma.

Penetrating head trauma requires immediate surgery to repair damage.

Diffuse axonal injury is seen in severe trauma. Head CT scan shows no mass lesion, but multiple small lesions involving the gray-white matter interface.

Neck Injuries

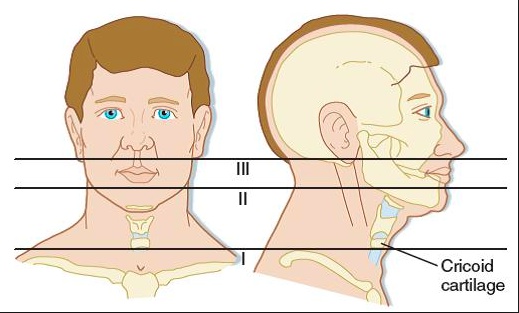

In order to help guide management, the neck is divided into the following 3 zones:

Zone I: Inferior to the cricoid cartilage

Zone II: Between the cricoid cartilage and angle of the mandible

Zone III: Superior to the angle of the mandible

Penetrating neck injuries warrant surgical exploration if any of the following conditions are present:

The patient’s vitals are deteriorating (i.e. hemorrhagic shock)

There is an expanding hematoma, which can acutely compromise the airway

There are signs of tracheal or esophageal injury (e.g. hemoptysis, subcutaneous emphysema)

In patients with penetrating neck injuries (e.g. gun shot or stab wounds), the following tests are necessary to rule out surgical intervention or determine surgical approach:

Arteriography

Esophagogram (water-soluble, then barium if negative)

Esophagoscopy

Bronchoscopy

If patients with severe blunt trauma to the neck have neurologic deficits or evidence of a fracture (e.g. point tenderness on c-spine palpation), then a CT scan of the cervical spine is indicated.

Shock

In the setting of traumatic injury, shock is usually caused by:

Hypovolemia/hemorrhage (most common cause in trauma patients)

Acute pericardial tamponade

Tension pneumothorax

Neurogenic (spinal cord injury)

Hypovolemic

The most important clinical feature that distinguishes hypovolemia/hemorrhage from tension pneumothorax and pericardial tamponade in a tachycardic trauma patient is flat neck veins (low CVP).

The first step in management of a patient with hypovolemia/hemorrhagic is volume replacement with intravenous fluids. 2 liters of normal saline or lactated ringers are given as fast as possible through large-bore (e.g. 14-gauge) peripheral IVs. This is followed by blood (packed red cells). The general rule for trauma resuscitation is 3 ml of fluid is needed for each ml of blood lost ("3-to-1 rule"). Note: Colloids (vs. crystalloids) have not been shown to improve mortality in hemorrhagic patients.

During trauma resuscitation of a hypovolemic/hemorrhagic patient, the target urine output is 0.5-2.0 ml/kg/h. However, the central venous pressure (CVP) should not exceed 15 mmHg.

If peripheral IV access cannot be established quickly, alternatives include:

Intraosseous cannulation (e.g. proximal tibia) (most common in modern trauma setting)

Percutaneous femoral/jugular vein catheters

Saphenous vein cut-downs

Tamponade

A patient with pericardial tamponade will have the following clinical features:

Trauma to the chest (e.g. penetrating chest trauma most common)

Distended head and neck veins (high CVP)

Hypotension

Muffled heart sounds

Beck Triad = Hypotension, JVD, muffled heart sounds

Pericardial tamponade is a medical emergency and is usually diagnosed clinically. When diagnosis is unclear, sonogram (FAST) is used for confirmation. Immediate pericardial sac evacuation by pericardiocentesis, tube, pericardial window, or open thoracotomy is required for treatment.

acute: small amount of blood needed, normal cardiac silouette

chronic: heart adapts, large amount of blood needed, large cardiac silouette

Pneumothorax

A patient with a tension pneumothorax will have the following clinical features:

Trauma to the chest (e.g. GSW, stabbing)

Distended head and neck veins (high CVP)

Hypotension

Severe respiratory distress

On physical exam of the chest of a patient with tension pneumothorax, the affected side has no breath sounds and is hyperresonant to percussion. On x-ray, the mediastinum is displaced to the opposite side,marked most notably by tracheal deviation.

Since a tension pneumothorax is a clinical diagnosis and a medical emergency, NO chest x-ray or other study is necessary and is contraindicated. Management is insertion of a large-bore needle or IV catheter into the pleural space (inserted high on anterior chest wall in the second intercostal space) then insertion of a chest tube and connect it to underwater seal and suction (chest tube also inserted high on anterior chest wall).

The first three steps in management of a tension pneumothorax are:

Emergent needle decompression, inserted into the 2nd intercostal space

Chest tube (tube thoracostomy), inserted into the 5th intercostal space

Intubation, if still necessary

Note that diagnostic imaging plays no role in the emergent stabilization of these patients.

Neurogenic

The most important clinical feature to distinguish neurogenic shock from the other forms of trauma shock is bradycardia. Other signs and symptoms include:

Flaccid paralysis

Hypotension

Cutaneous vasodilation

Thoracic Trauma

Thoracic trauma is unique in that blunt trauma may cause secondary penetrating trauma via fractured rib penetration. Therefore, penetrating trauma must be considered in any case of thoracic trauma.

Due to the curvature of the diaphragm, one cannot rule out abdominal trauma that occurs below the nipple line.

Pain on breathing from rib fractures and other injuries in thoracic trauma may limit chest wall excursion. Management in these cases centers around local anesthesia, as opposed to pain medications that may decrease respiratory drive.

Both tension pneumothorax and pericardial tamponade can cause extrinsic compression of the heart and acute heart failure, and must be considered as differential diagnoses of hypotensive tachycardia in the setting of thoracic trauma. Note that these are both clinical diagnoses; taking time for diagnostic imaging risks increased mortality.

Both of these pathologies are differentiated from hypovolemic shock by the presence of distended neck veins.

Blood in pericardial sac is indicative of tamponade.

Pulmonary exam findings of decreased breath sounds and hyperresonant percussion are indicative of tension pneumothorax.

Sucking chest wounds are those that visibly can be seen to suck in air, and can lead to a tension pneumothorax. Management is bandaging with an occlusive dressing taped at only 3 points, which acts as a one-way valve to let air out of the thorax. Intubation and further surgical management may be needed.

Hemothorax

Hemothorax, an accumulation of blood outside the visceral lung pleura, is a differential diagnosis of decreased breath sounds along with pneumothorax. However, it is differentiated by the presence of dullness to percussion on physical exam.

The management of hemothorax is often non-emergent, as parenchymal lung bleeding is often self-limiting. Initial management is a chest tube (tube thoracostomy).

Either a massive immediate drainage (greater than 1.5 L) or large ongoing drainage of the chest tube (200 to 300 ml per hour) warrants surgical intervention with thoracotomy to ligate the vessel. Bleeding in this manner is known to be thoracic (e.g. intercostal artery), as opposed to pulmonary parenchymal.

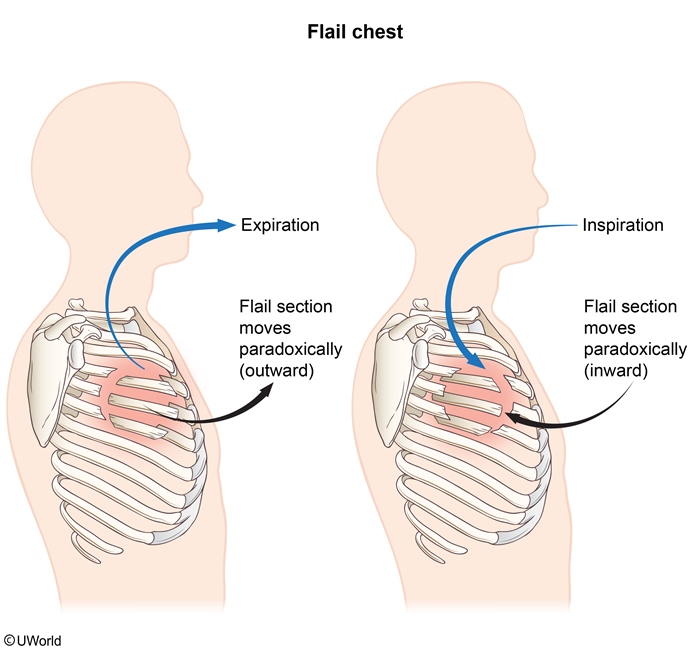

Flail Chest

A flail chest is a segment of chest wall that exhibits paradoxical respiratory mechanics (i.e. expansion on expiration) correctable by PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure). It occurs when segments of ribs are broken in two places to create a separate segment of chest wall.

Respiratory failure can occur, often due to associated pulmonary contusion and resultant collection of edema and blood in the alveoli

The best early treatment of a flail chest is pain control and supplemental oxygen to maximize excursion and oxygenation.

If patients with flail chest are intubated and PEEP is utilized, prophylactic chest tubes on the side where rib fractures are located are warranted to prevent pneumothorax.

Pain control and supplemental oxygen are the most important early steps in managing this condition. However, respiratory failure often occurs due to associated pulmonary contusion and accumulation of edema/blood in the alveoli, and intubation with mechanical positive pressure ventilation (MPPV) is required in many patients. In addition to improving oxygenation, MPPV also corrects the paradoxical motion of the flail segment by replacing the normal negative intrapleural pressure with positive intrapleural pressure and forcing the segment to move outward with the rest of the rib cage during inspiration. Lung puncture due to sharp rib edges and resulting tension pneumothorax are potential complications of MPPV in the management of flail chest. Although it is not required, bilateral chest tube placement prior to intubation can help minimize this risk.

Alarming Signs

There are 4 signs of trauma that are extreme enough to warrant active investigation for occult secondary complications of trauma. These signs are:

Sternum fracture

1st rib fracture

Scapula fracture

Flail chest formation

If any of these four signs of extreme thoracic trauma are present, the patient must be prophylactically evaluated for the following complications:

Pulmonary contusion

Myocardial contusion

Aortic rupture

Initial evaluation includes chest radiograph, EKG, and cardiac enzymes for these complications.

Aortic Rupture

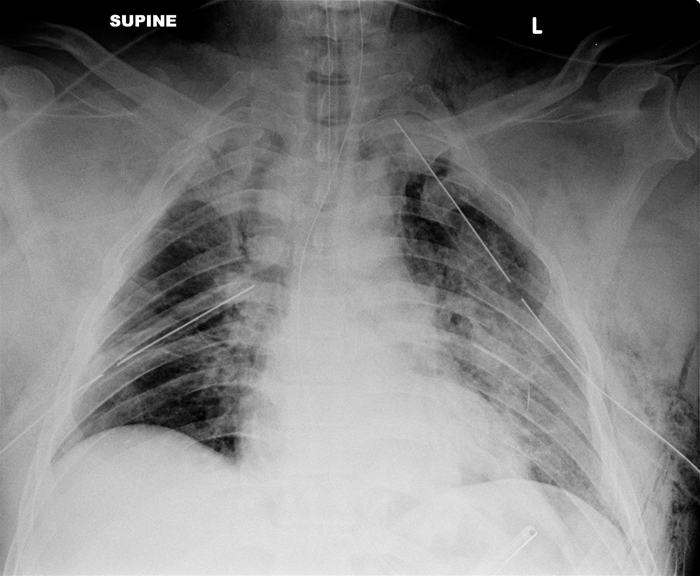

The first diagnostic study to evaluate a patient for a traumatic aortic rupture is a chest x-ray. Finding of a widened mediastinum on chest x-ray is highly concerning.

Most patients with aortic rupture die in the field. Those that survive to the emergency department typically have suffered an injury of the aorta just distal to the left subclavian artery that may be contained as hematomas within the mediastinum. This form of aortic rupture typically causes hypertension (due to visceral afferent reflexes and a pseudocoarctation syndrome) and not jugular venous distention.

Regardless of CXR results, if clinical suspicion of traumatic aortic rupture is high, the next diagnostic study to perform is either a chest CT or a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). The two tests have comparable sensitivity and specificity, with TEE being preferable in unstable patients.

The final diagnostic study that may be needed in the evaluation of a potential aortic rupture is an arteriogram. Arteriograms are only indicated in the case of a positive chest radiograph and negative follow-up CT/TEE with high clinical suspicion.

Pulmonary Contusion

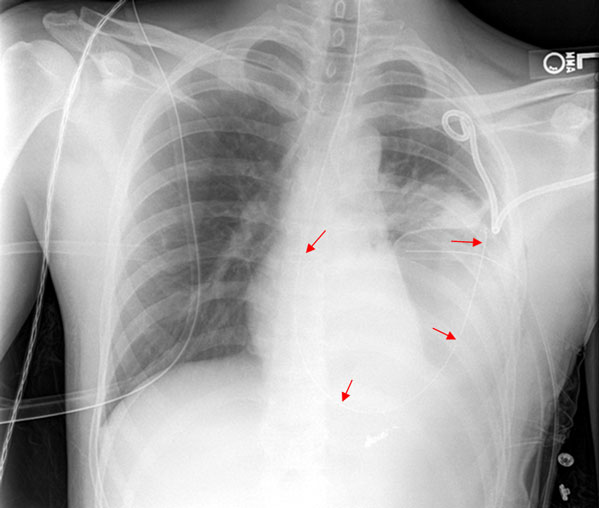

Pulmonary contusions are parenchymal injuries that can cause hypoxia in the acute setting. Classically, pulmonary contusions may not be immediately apparent radiographically, but later show a bilateral "white-out" appearance due to diffuse opacities.

Pulmonary contusions have a similar pathophysiology to ARDS in that they are characterized by increased vascular permeability and intraalveolar hemorrhage. Besides breathing and oxygenation monitoring, treatment of pulmonary contusion centers around fluid restriction and diuretics.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a common complication of PC. However, ARDS usually manifests 24-48 hours after trauma and demonstrates bilateral, patchy alveolar infiltrates on chest x-ray.

Myocardial Contusion

Myocardial contusion may also result from blunt trauma. Tachycardia is a common sign, and chest x-ray may demonstrate rib fractures, a common cause of cardiac contusion. Other symptoms include new bundle branch blocks or arrhythmia. Sternal fracture is a commonly associated finding. Mediastinal widening is not seen with myocardial contusion alone. Can have increased PCWP with infusion of saline suggesting left ventricular dysfunction.

Diaphragmatic Rupture

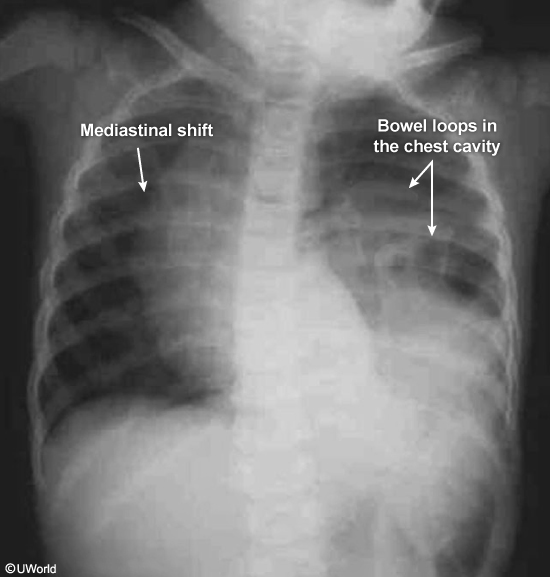

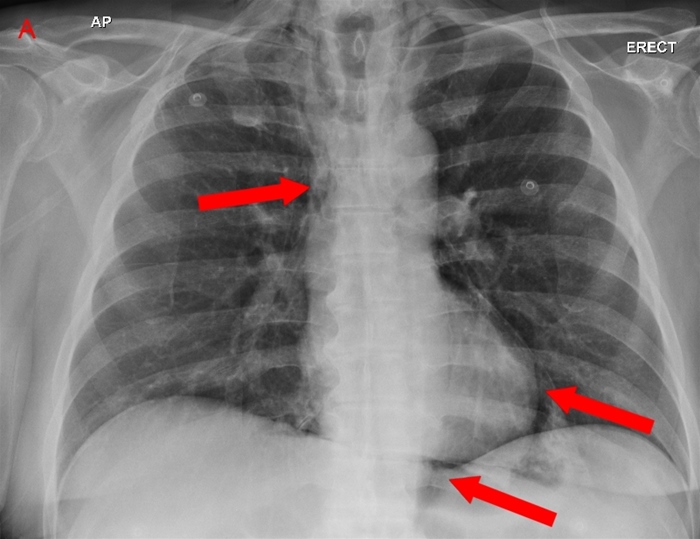

Diaphragmatic ruptures most commonly occur on the left, because the liver prevents right-sided rupture. Two radiographic findings on chest x-ray are multiple air-fluid levels and presence of nasogastric tube in the thorax.

Blunt abdominal trauma due to motor vehicle accident can significantly raise intra-abdominal pressures and lead to diaphragmatic rupture or avulsion from its attachments. The left diaphragm is more prone to injury than the right due to congenital weakness in the diaphragm's left posterolateral region and the liver's protective effects on the right side. Some patients (especially children) with traumatic diaphragmatic injury may initially have no symptoms or signs and can have a delayed presentation (months to years) with expansion of the diaphragmatic defect and herniation of abdominal organs. This delayed diagnosis is associated with a high morbidity and mortality and can increase the risk of hernia formation and strangulation.

Elevation of the hemidiaphragm on the chest x-ray might be the only abnormal finding, but ultrasonography or CT scan of the chest is sometimes required if the chest x-ray does not visualize the area well. The small bowel is sometimes present in the thoracic cavity.

The treatment is surgical correction.

Tracheobronchial rupture

Tracheobronchial injury can lead to extravasation of air into other tissues and persistent respiratory trouble. Suspect rupture of the trachea or bronchi when a pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum persists despite chest tube placement and other stabilization measures. Also can have subcutaneous emphysema. Right main bronchus most commonly injured.

The next best step in evaluation of a tracheobronchial injury is bronchoscopy.

Esophageal rupture

An esophageal rupture typically presents with severe retrosternal chest pain and mediastinal free air on chest x-ray and does not cause massive blood loss or cardiac pump failure unresponsive to standard fluid resuscitation. Also can have subQ crepitus.

Air Embolism

Air embolism following major thoracic trauma might present with acute circulatory failure or neurologic signs (eg, focal weakness, facial droop, dysarthria)

Urologic

Causes

Urological injuries are often overlooked in the initial evaluation of a trauma patient but need to be suspected in the following situations:

Straddle injury

Penetrating injury to lower abdomen

Fall from a height

Gross hematuria

Pelvic fracture: posterior hip dislocation

Symptoms

The most common signs and symptoms of urethral injury include:

Blood at the urethral meatus

Ecchymoses or hematoma involving penis, scrotum, or perineum

"High riding", or superiorly displaced, prostate. Prostate and prostatic urethra torn from urethra and pulled cephalad thus the prostate feels “too far up” on per rectal examination.

Inability to void

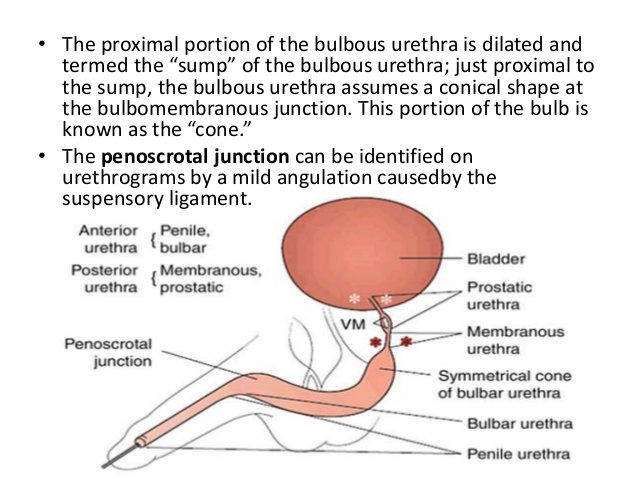

The bulbomembranous junction (junction of the anterior and posterior urethra) is the most common site of urethral injury. However, the urethra is an extraperitoneal structure, so its injury does not lead to peritonitis. In posterior urethral injury (eg, membranous urethral injury) and bulbomembranous transection, digital rectal examination may reveal a high-riding prostate. In the case of anterior urethral injury, penile trauma (eg, laceration, contusion) is often visible.

Management

Urethral

When an urethral injury is suspected, before a Foley can be placed retrograde urethrogram must be done to evaluate the extent of the urethral injury. (not retrograde cystogram that's used for bladder injuries)

This diagnostic test involves an x-ray of the lower genitourinary tract obtained during the injection of radiopaque contrast into the urethra. A normal study demonstrates contrast entering the bladder uninterrupted. Extravasation of contrast from the urethra or inability of contrast to reach the bladder is diagnostic of urethral injury.

(Note: While the digital rectal exam is classically taught to be useful in the initial evaluation of urethral injury, multiple retrospective and observational studies demonstrate a lack of sensitivity and utility in the DRE.)

Anterior urethral injury is treated with immediate surgery; posterior urethral injury is treated with suprapubic cystostomy tube placement and delayed repair.

Urethral injury is more common in men and occurs in approximately 25% of male pelvic fractures. The ability to pass a Foley catheter into the bladder makes urethral injury unlikely. In addition, this patient lacks physical examination findings suggestive of urethral injury (eg, blood at the urethral meatus, high-riding prostate).

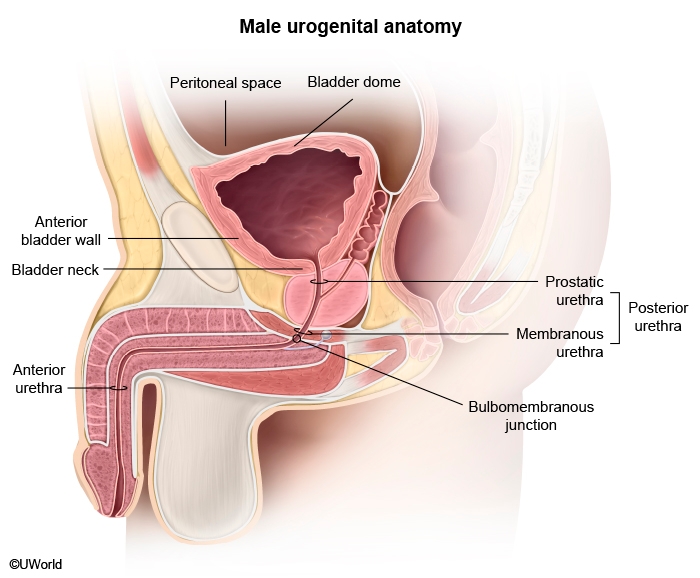

Bladder

Bladder injuries are usually associated with pelvic fractures. Intraperitoneal bladder rupture is treated with surgery; extraperitoneal bladder rupture is treated with non-surgical management by Foley drainage or suprapubic cystostomy tube.

This patient likely has an extraperitoneal bladder injury (EPBI), which may consist of either contusion or rupture of the neck, anterior wall, or anterolateral wall of the bladder. In the case of rupture, extravasation of urine into adjacent tissues causes localized pain in the lower abdomen and pelvis. Pelvic fracture is almost always present in EPBI, and sometimes a bony fragment can directly puncture and rupture the bladder. Gross hematuria is also usually present, and urinary retention (evidenced by suprapubic fullness in this patient) may occur, especially in the case of injury to the bladder neck.

Intraperitoneal bladder rupture describes rupture of the dome of the bladder; the dome is composed of the superior and lateral bladder walls and directly abuts the peritoneal space. Rupture of this area results in intraperitoneal urine leakage and typically presents with signs of chemical peritonitis (eg, diffuse abdominal tenderness, guarding, rebound), which are absent in this patient. Pelvic fracture is often present but less commonly than in EPBI.

In the setting of blunt abdominal trauma, spillage of blood, bowel contents, bile, pancreatic secretions, or urine into the peritoneal cavity can cause acute chemical peritonitis, which is evidenced by diffuse abdominal pain and guarding. The superior and lateral surfaces of the bladder compose the dome of the bladder and are bordered by the peritoneal cavity. Therefore, rupture of the dome of the bladder causes urine to spill into the peritoneum, leading to peritonitis. Bladder rupture after blunt trauma is due to a sudden increase in intravesical pressure and most likely occurs following a blow to the lower abdomen when the bladder is full and distended.

In addition, irritation of the peritoneal lining of the right or left hemidiaphragm may cause referred pain to the ipsilateral shoulder (Kehr sign) as sensory innervation to the shoulder originates from the C3 to C5 spinal roots; these roots are also the origin of the phrenic nerve innervating the diaphragm.

Renal

Abdominal CT scan with contrast is used to diagnose renal and ureteral injuries. Intravenous pyelogram (IVP) is also used to diagnose ureteral injuries.

Renal laceration may present with hematuria, but urinary retention would be unusual. Patients with this injury usually have flank pain and hemorrhage into the retroperitoneal space.

Renal injuries can be usually managed conservatively. Only severe injuries, such as vascular injury or parenchymal laceration extending through the renal cortex, medulla, and collecting system, warrants surgery.

Ureteral

Ureteral injuries, usually found searching for renal injuries, are the least common GU tract injury and must be surgically repaired.

The most common cause of ureteral injury is iatrogenic trauma during abdominal surgery. Injury due to blunt trauma is relatively rare. When it does occur, the most common site is the ureteropelvic junction. In such cases, hematuria may be present, and fever, flank pain, and a renal mass (from hydronephrosis) may develop several hours after injury.

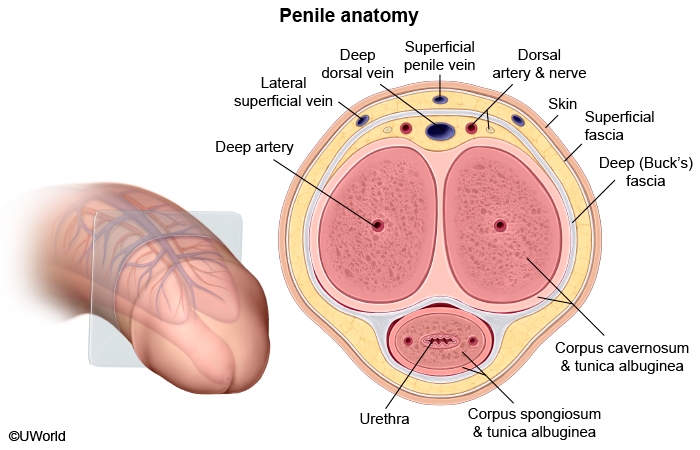

Penis Fracture

Penis fractures usually occur when the penis is erect during vigorous sexual intercourse.

The signs and symptoms of a fracture of the penis are:

Sudden pain

Hematoma of the penis shaft

Normal appearing glans

Fracture of the penis (i.e. fracture of the corpus cavernosa, fracture of the tunica albuginea) requires immediate urethrogram to evaluate urethral damage followed by surgical intervention.

Complications of a untreated penis fracture include development of an arteriovenous shunt and impotence.

This patient has a classic presentation of penile fracture (PF), which results from the rupture of the corpus cavernosum due to a traumatic tear in the tunica albuginea (which envelopes the corpus cavernosum). PF is most frequently encountered when the penis is in the erect state. Patients typically experience an audible snapping sensation, detumescence, and minimal to severe pain (depending on severity of the injury); a hematoma forms rapidly, causing bending of the shaft of the penis at the fracture site.

Diagnosis is usually clinical, and surgical management of PF, a urological emergency, is the mainstay of treatment. The only imaging test commonly used in evaluation is retrograde urethrogram, which is employed in cases of suspected urethral injury, a common complication. Indications for urethrogram include:

Blood at the meatus

Hematuria

Dysuria

Urinary retention

Amputations

All patients suffering traumatic amputations should be treated as candidates for reimplantation while in the field. As such, their amputated limb or digit should be wrapped in sterile gauze, moistened with sterile saline and placed in a plastic bag. The bag should be then placed on ice and transported with the patient to the nearest emergency department. The amputated part should not be allowed to freeze. Packaging of the amputated part in this manner prolongs the viability of the part for up to 24 hours. Younger patients suffering sharp amputations with no crush injury or avulsion are the best candidates for amputation reimplantation.

Extremity Vascular Trauma

Extremity vascular trauma

Clinical manifestations

Hard signs: Observed pulsatile bleeding. Presence of bruit/thrill over injury. Expanding hematoma. Signs of distal ischemia. Soft signs: History of hemorrhage. Diminished pulses. Bony injury. Neurologic abnormality.

Evaluation

If hard signs or hemodynamic instability: Surgical exploration. Otherwise: Injured extremity index. CT scan or conventional angiography. Duplex Doppler ultrasonography

This patient with a penetrating injury to the anteromedial portion of the upper thigh and hard evidence of vascular injury should undergo prompt surgical exploration. The initial evaluation and management of patients with severe extremity injury includes hemorrhage control, radiography of skeletal injuries, and evaluation of the neurovascular bundle. Vascular assessment should focus on identifying hard signs of injury, including:

Observed pulsatile bleeding

Presence of a bruit or thrill over the injury

Expanding hematoma

Signs of distal ischemia (eg, absent pulses, cool extremities)

In the presence of a penetrating injury, such signs (with or without hemodynamic instability) are almost universally predictive of the need for urgent surgical repair and warrant immediate exploration. If the area of damage is unclear, arteriography can be performed intraoperatively to clarify anatomy.

If hard signs are absent, further evaluation for soft signs (eg, history of hemorrhage, diminished pulses, bony injury, neurologic abnormality) should occur. If present, these signs indicate the need for additional testing such as the injured extremity index (similar to ankle-brachial index), which involves comparing the systolic occlusion pressure distally in an injured extremity to the occlusion pressure at a proximal site in an uninjured extremity. If the index is abnormal (<0.9), patients should be considered for CT scan or conventional arteriography and surgery in conjunction with management of other injuries (eg, bony damage).

Succinylcholine

Succinylcholine is a depolarizing neuromuscular blocker that works by binding to postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors to trigger influx of sodium ions and efflux of potassium ions through ligand-gated ion channels; depolarization occurs and temporary paralysis ensues (delayed repolarization of the skeletal muscle membrane). Succinylcholine is often used during rapid-sequence intubation as it has a rapid onset (45-60 seconds) and offset (6-10 minutes) of action. However, in certain patients it can cause life-threatening cardiac arrhythmia due to severe hyperkalemia.

This patient has experienced an extensive skeletal muscle crush injury, which places him at risk for hyperkalemia due to skeletal muscle cell lysis (rhabdomyolysis). In addition, skeletal muscle injury leads to upregulation of postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors, which can result in massive efflux of potassium following administration of succinylcholine. Other relevant conditions that cause upregulation of acetylcholine receptors include burn injury, disuse muscle atrophy, and denervation (eg, stroke, Guillain-Barré syndrome, critical illness polyneuropathy). To avoid life-threatening hyperkalemia in such settings, nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents (eg, vecuronium, rocuronium) should be used as they do not affect postsynaptic ligand-gated ion channels.

Halothane can lead to acute liver failure due to production of hepatoxic intermediary compounds; therefore, it is now rarely used. Adult women are at greatest risk of developing halothane-associated liver toxicity.

(Choice B) Etomidate inhibits 11β-hydroxylase and can lead to adrenal insufficiency. The elderly and patients with critical illness (eg, sepsis) are typically susceptible.

(Choice D) Nitrous oxide inactivates vitamin B12, leading to inhibition of methionine synthase activity; subsequent neurotoxicity (eg, peripheral neuropathy) can result in patients with preexisting vitamin B12 deficiency.

(Choice E) Severe hypotension due to myocardial depression is a common adverse effect of propofol. Therefore, propofol should be avoided or used with extreme caution in patients with ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Last updated