Labor

Normal Labor

Labor usually begins between 37 to 42 weeks’ gestation and it involves four stages of progression.

First Stage

The first stage of labor includes three phases:

Latent phase

Active phase

Deceleration phase

Latent

The latent phase begins with the onset of contractions resulting in cervical dilation or effacement (thinning) until 6 cm of cervical dilation and complete effacement.

Note: This definition has recently changed, in the June 2014 ACOG definitions update. Older sources may use 4cm as the cutoff value.

The latent phase of the first stage of labor is typically less than 20 hours for nulliparous women and less than 14 hours for multiparous women. ⅔ of the time is spent in the latent, and ⅓ in the active phase.

Active

The active phase lasts from 6 cm cervical dilation until near 10 cm of cervical dilation with consistent progression.

It is marked by regular uterine contractions, quick progression of cervical dilation (1.2 cm/hour for nulliparous and 1.5 cm/hour for multiparous women) and effacement.

The four Ps affect the length of the active phase of labor.

Power, which refers to the strength and frequency of contractions

Passenger, which refers to the size and position of the neonate

Pelvis, which refers to the size and shape of the mother’s pelvis

Parity, which refers to previous vaginal deliveries

Deceleration

The deceleration phase is the transition point from the active phase to the second stage of labor. It is marked by a slowing of dilation and effacement.

Management of the first stage of labor includes monitoring fetal heart rate and uterine contractions in order to assess the progression of cervical changes periodically during the active phase.

Second Stage

The second stage of labor is the time from complete dilation of the cervix (full 10 cm) until delivery.

The second stage consists of fetal descent through the birth canal driven by uterine contractions.

Some clinicians further divide the second stage of labor into two phases when pushing is delayed. The first phase is passive. The passive phase of second stage of labor begins when the cervix is completely dilated but before the mother is actively trying to expel the fetus.

If labor is delayed, some clinicians divide the second stage of labor into two phases. The second is the active phase. It is when the mother is actively pushing to expel the fetus, and ends when the baby is delivered.

Management of the second stage of labor includes monitoring fetal heart rate and movement through the birth canal.

The second stage of labor lasts:

<2 hours in nulliparous women

<3 hours in nulliparous women with an epidural

<1 hour in multiparous women

<2 hours in multiparous women with an epidural

Arrest of dilation is diagnosed when:

The patient's cervix is at least 6 cm dilated AND

Membranes are ruptured (spontaneously or artificially), AND

There has been no cervical change (dilation or effacement) after:

4 hours of adequate contractions OR

6 hours of inadequate contractions while on synthetic oxytocin

To determine whether contractions are adequate, an intrauterine pressure catheter must be placed. It allows the clinician to quantify the strength of the contractions. Add up the peak-to-trough height of each contraction in a 10-minute period. The units are Montevideo units, and contractions are considered adequate when there are at least 200 Montevideo units.

Third Stage

The third stage of labor is the time from the delivery of the infant to the delivery of the placenta.

The placenta generally separates from the uterine wall within 30 minutes after delivery of the neonate and emerges through the birth canal. The uterus contracts to both expel the placenta and to prevent hemorrhage.

Active management of the third stage of labor is recommended over expectant management for the following reasons:

Shorter third stage of labor

Reduced risk of postpartum hemorrhage and severe postpartum hemorrhage

Reduced risk of anemia

Decreased need for blood transfusion

Decreased need for additional uterotonic medications

Active management of the third stage of labor include:

Administer oxytocin

Controlled cord traction

Fundal massage

The three signs that the placenta has separated from the uterine wall include:

Cord lengthening

A rush of blood

Elevation of fundal height

Retained placenta is when the placenta does not deliver within 30 minutes. This often occurs with preterm deliveries and should be removed with manual extraction or curettage.

Placenta accreta may less commonly be a cause of retained placenta, for which the management is hysterectomy.

The third stage of labor lasts 0-30 minutes in both nulliparous and multiparous women.

Fourth Stage

The fourth stage of labor is defined as the initial postpartum hour and is marked by the hemodynamic stabilization of the mother.

The fourth stage of labor is managed with maternal pulse and blood pressure monitoring in order to look for signs of hemorrhage.

Preterm Labor

Preterm labor refers to the onset of labor before 37 weeks’ gestation.

Risk factors include:

Prior preterm labor

Shortened cervix

Multiple gestations

Preterm premature rupture of membranes

Chorioamnionitis

Uterine anomalies and placental abruption

Preeclampsia

Low socioeconomic status

Smoking and substance abuse

Patients experiencing preterm labor present with any of the following before 37 weeks gestation:

Constant low back pain

Feeling of lower abdominal or pelvic pressure

Regular cramping or contractions (Note: No specific duration or interval is generally accepted, only that the contractions are consistent from one contraction to the next. Reputable sources quote intervals anywhere from 3 to 10 minutes as suggestive of preterm labor.)

While it is not strictly part of the patient presentation, remember that the physical exam of a patient in preterm labor will demonstrate cervical dilation and/or effacement.

Patients should be tested for:

Urinary tract infection (urinalysis, urine culture)

Bacterial vaginosis (nitrazine test, saline wet prep, KOH test)

Fetal fibronectin testing is useful in select patients (see below for more information).

Ultrasound should be used to

assess amniotic fluid volume

verify fetal well-being

verify gestational age

verify fetal position (vertex, breech, or transverse)

measure cervical length (transvaginal)

Ultrasound can also be used to measure cervical length. A cervical length >35 mm is associated with a very low risk of preterm birth and a length <15 mm has a high risk of preterm birth.

If the cervix is found to be shortened, measurement of fetal fibronectin levels in vaginal fluids can aid in risk stratification. If fetal fibronectin is present in the fluid, the patient is more likely to be in preterm labor. Note: Like d-dimer testing for pulmonary embolism, fFN testing has a high negative predictive value but a low positive predictive value. It is a rule-out test.

Premature infants are at increased risk for:

Respiratory distress syndrome (worsens with shorter gestational age)

Intracranial hemorrhage (aka intraventricular hemorrhage)

Sepsis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)

Management

Management varies based on whether the gestational age is less than 34 weeks’ gestation or greater than 34 weeks’ gestation.

Preterm labor is likely in the following circumstances and should be managed accordingly:

Cervical dilation ≥ 3 cm

Cervical dilation < 3 cm

Cervical length < 20 mm

Cervical length between 20 and 30 mm with positive fibronectin test

If preterm labor is likely, it should be managed with the following:

Expectant management (even if preterm premature rupture of membranes)

Hospitalization, hydration, and activity restriction

Tocolytic therapy for 48 hours

Glucocorticoids (betamethasone or dexamethasone) for 48 hours to assist with fetal lung maturation

Empiric penicillin for prophylaxis against group B strep if delivery is imminent

If delivering at less than 32 weeks gestation, magnesium sulfate should be added to the above, for neuroprophylaxis (prevention of cerebral palsy in surviving infants).

When indicated, tocolytic agents can be used in women 24 to 34 weeks gestation.

Indomethacin is used as first-line for tocolysis for women 24 to 32 weeks gestation, with nifedipine as second-line therapy. Nifedipine is first-line agent for women 32 to 34 weeks gestation.

At gestational age less than 34 weeks and the cervix dilated less than 3 cm, the following should be performed:

Specimen for fetal fibronection testing should be obtained, but held until results of ultrasound

Transvaginal ultrasound to measure cervical length

For patients under 34 weeks of gestational age with a cervix dilated < 3 cm, cervical length between 20 and 30 mm, and negative fetal fibronection test, preterm labor is unlikely and they should be managed with the following:

Observe for 6 to 12 hours

Discharged home, if no progressive cervical dilation and effacement

Followup in 1 to 2 weeks

Call if additional signs and symptoms of preterm labor

For patients under 34 weeks of gestational age with a cervix dilated < 3 cm and cervical length > 30 mm, preterm labor is unlikely and they should be managed with the following:

Observe for 4 to 6 hours

Discharged home, if no progressive cervical dilation and effacement

Followup in 1 to 2 weeks

Call if additional signs and symptoms of preterm labor

At greater than 34 weeks gestation, preterm labor should be managed with the following:

Expectant management if fetal lung maturity has been proven

Active managementif there is an indication for delivery, such as nonreassuring fetal testing, infection, or maternal threat

Tocolysis and glucocorticoids have no proven benefit after 34 weeks’ gestation.

Empiric penicillin for group B strep prophylaxis if the patient is group B strep positive (or group B strep status is unknown) and delivery is imminent

Patients with a singleton pregnancy and a history of a prior preterm delivery should be offeredintramuscular 17-alpha progesterone injections (Makena)starting at 16-24 weeks' gestation. Treatment should continue until 37 weeks' gestation (or until delivery is indicated).

Cervical insufficiency leads to painless cervical dilation in the second trimester. It should be suspected in a patient with a history of second-trimester pregnancy loss without painful contractions.

If a cervical length < 20 mm is identified on ultrasound at <24 weeks' gestation and there is no prior history of spontaneous preterm birth, vaginal progesterone supplementation should be offered.

Cerclage is a procedure in which a nonabsorbable suture is placed in the cervix to prevent cervical dilation. It is used to prevent preterm birth in patients with cervical insufficiency.

Cerclage may be indicated in the following patients with singleton pregnancies:

History-indicated cerclage: one or more second-trimester pregnancy losses related to painless cervical dilation (without labor or placental abruption) OR prior cerclage for painless cervical dilation in the second trimester (prior physical exam-indicated cerclage)

Exam-indicated, or "rescue" cerclage: Physical exam demonstrating painless cervical dilation in the second trimester

Ultrasound-indicated cerclage:Ultrasound showing short cervix (<25mm) before 24 weeks' gestation and a history of a spontaneous preterm birth at <34 weeks.

Risk factors for cervical insufficiency include a history of

history of preterm delivery

cervical instrumentation (D&C, LEEP, conization)

cervical trauma (tearing during delivery)

congenital conditions(uterine anomalies, in-utero DES exposure, connective tissue disorders)

Labor Induction

Inducing labor refers to intervening to initiate uterine contractions prior to the onset of labor. Labor augmentation is used to speed the progress of labor.

Agents commonly used to induce labor include oxytocin (Pitocin) and misoprostol (Cytotec).

Inducing labor is indicated when the maternal/fetal risks of continuing the pregnancy are greater than with early/induced delivery.

Maternal indications for inducing labor include:

Preeclampsia, eclampsia, or HELLP syndrome

Diabetes mellitus

Chorioamnionitis

Abruptio placentae

Fetal indications for inducing labor include:

Prolonged, or postterm pregnancy (>40-42 weeks gestation)

Intrauterine growth restriction

Premature rupture of membranes (PROM)

Multiple gestation

Some congenital defects

Fetal demise

Induction of labor is not indicated for the following reasons:

Maternal anxiety or normal discomfort from pregnancy

A previous pregnancy with labor abnormalities

Note: Patients with a history of shoulder dystocia are often given the option of an elective cesarean section.

Elective induction should not be performed before 39 weeks’ gestation because of the increased risk of neonatal morbidity.

Pitocin

Synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin) is identical to the oxytocin produced by the hypothalamus. It is used to induce labor and control postpartum bleeding by inducing contraction of the uterine myometrium.

Adverse effects associated with the use of synthetic oxytocin for labor induction include:

Uterine tachysystole and concomitant fetal hypoxemia

Hyponatremia (oxytocin is structurally similar to ADH)

Hypo- and hypertension

Note: Uterine tachysystole is defined as >5 contractions in 10 minutes within a 30-minute window.

Tachysystole accompanied by fetal heart rate changes should prompt discontinuation of synthetic oxytocin until the fetal heart rate normalizes.

Contraindications to the use of synthetic oxytocin include:

Fetal distress

Premature delivery

Unfavorable fetal position

Mechanical Dilators

Oxytocin does not induce cervical ripening, so mechanical dilators or pharmacologic agents are sometimes given to ripen the cervix.

Mechanical dilators such as laminaria and foley bulbs are very small (0.3cm diameter), but it can be difficult to insert them into a completely closed cervix. Insertion is much simpler and less uncomfortable for the patient if her cervix is at least "fingertip" dilated.

Foley bulb induction involves the placement of the balloon portion of a Foley between the amniotic sac and the internal cervical os. The bulb is then inflated with saline solution in order to mechanically open the cervix. The bulb slides out on its own when the cervix dilates to 3-4cm.

Labor may start on its own once the cervix is ripened, or pitocin may be used to induce contractions.

Hygroscopic dilators, including those using laminaria algae, may be used to mechanically dilate the cervix prior to starting pitocin for induction of labor. However, these tools are much more commonly used to soften the cervix before first-trimester terminations or other procedures which require passage of instruments of the cervix.

Misoprostol

Misoprostol (Cytotec) is a PGE1 analogue that causes cervical ripening and induces uterine contractions.

Note: Remember that uterine prostaglandins lead to painful uterine contractions (cramping) in patients with primary dysmenorrhea.

Misoprostol (Cytotec) is contraindicated in patients with prior cesarean delivery and any preexisting evidence of uterine activity.

Dinoprostone (Cervidil) is a PGE2 analogue that softens the cervix and induces uterine contractions. It can be significantly more expensive than misoprostol, but it is released through a timed-release mechanism, and is currently the only medication for cervical ripening that is FDA-approved for this purpose.

Contraindication

Contraindications to induction of labor are situations in which inducing labor would pose greater maternal/fetal risk than performing a cesarean section.

Settings in which induction of labor is contraindicated include:

Prior uterine rupture or surgery

Active genital herpes infection

Fetal lung immaturity

Malpresentation

Umbilical cord prolapse

Placenta previa

The likelihood of successfully inducing labor is based on cervical status. The Bishop score is the most reliable indicator of whether or not an induced labor will be successful.

A greater likelihood of successful vaginal delivery, and thus higher Bishop score, is associated with:

Greater cervical dilation and effacement

Softer cervix

More anterior cervical position

Greater (lower) station

A lower likelihood of vaginal delivery, and thus lower Bishop score, is associated with a higher likelihood of requiring a cesarean delivery (the likelihood of requiring a cesarean delivery after the attempted induction of labor is 30% if the Bishop score was calculated as <3 and 15% if >3).

C Section

Vertical cesarean sections involve an incision in anterior muscular portion of the uterus (classic vertical cesarean section) or lower uterine segment (low vertical cesarean section).

Indications for a vertical cesarean section include:

Transverse fetal presentation

Adhesions or fibroids preventing access to lower uterus

Hysterectomy is scheduled to follow delivery

Cervical cancer is present

Postmortem delivery to remove living fetus from dead mother

The risk of maternal mortality is similar for elective cesarean section and vaginal delivery, but an emergency cesarean section carries a higher risk of maternal and fetal mortality.

Risks to the mother include:

Anesthetic complications

Hemorrhage

Infection

Wound dehiscence

Bladder or bowel injury

Increased risk of DVT

In any following pregnancy, a vaginal delivery can only be attempted if a transverse cesarean section was performed.

If a classic (vertical) uterine incision was performed, there is a greater risk of uterine rupture with attempting a vaginal birth and a repeat cesarean delivery must be performed.

A cesarean section is an incision that is made in the uterine wall in order to deliver the fetus.

Cesarean sections account for approximately 1/3 of US deliveries and are on the rise.

The most common indication for a cesarean section is a prior cesarean section.

Maternal indications for a cesarean section include:

Prior uterine surgery (e.g., myomectomy) or prior classic cesarean section

Cardiac disease

Birth canal obstruction

Maternal death

Cervical cancer

Active genital herpes

Fetal indications for a cesarean section include:

Acute fetal distress

Malpresentation

Cord prolapse

Macrosomia

Combined maternal and fetal indications for a cesarean section include:

Failure to progress in labor

Placenta previa

Abruptio placentae

Cephalopelvic disproportion

The most common type of cesarean section is a low transverse, but a classic vertical incision allows more space to remove a fetus in a horizontal position.

Low transverse cesarean sections involve a transverse incision in the lower uterine segment. It is preferred to the classic technique and performed more commonly.

This type of cesarean section has a decreased risk of:

Uterine rupture

Bleeding

Bowel adhesions

Infection

Malpresentation

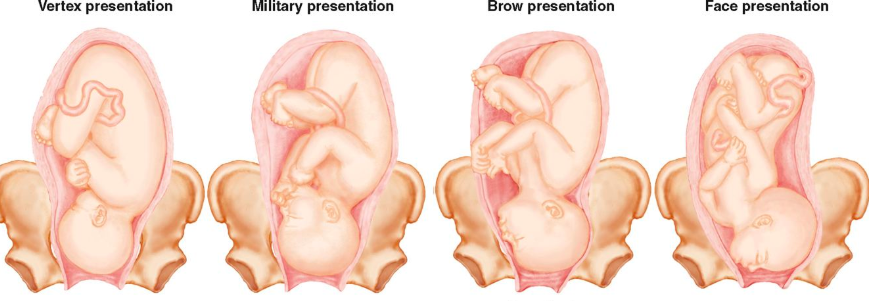

Cephalic

Normal fetal presentation, also known as cephalic or vertex, is where the fetal head is downward, with a tucked chin and the occiput aimed towards the birth canal.

Vertex presentation is the fetal position in >95% of pregnancies.

Face

Face presentation occurs rarely and is a full hyperextension of the fetal neck. It usually undergoes normal delivery as long as the fetal chin is anterior.

Brow

Brow presentation occurs very rarely and is a partial hyperextension of the neck, causing the largest surface area of the head aimed towards the birth canal. The presenting part is the portion of the fetal head between the orbital ridge and the anterior fontanel.

This presentation requires cesarean delivery if the head does not spontaneously correct to a normal presentation during labor.

Breech

Breech presentation is the most common malpresentation, which is where the buttocks, instead of the head, is directed towards the vaginal canal.

Breech presentation is noted in 25% of pregnancies before 28 weeks of gestation, but most of these become vertex by the time of birth.

Frank

Frank breech makes up 75% of cases and presents with flexed hips and extended knees so that the feet are near the head. Mnemonic: Frank has his Feet in his Face.

Complete

In a complete breech the fetal hips and knees are both flexed.

Footling

In a footling breech one or both of the fetal legs are extended so that the leg lies below the breech in the birth canal.

Risks

Risk factors for breech presentation include:

Prematurity

Multiple gestation

Polyhydramnios

Uterine anomaly

Placenta previa

Management

Abdominal examination by Leopold's maneuvers can detect the fetal head in the abdomen. Vaginal examination can detect the presenting part.

Performing an ultrasound will confirm breech position.

If breech position does not resolve by 37 weeks, it can be managed in one of three ways:

External cephalic version (ECV) may be used at 37 weeks gestation in an attempt to reposition the fetus, and is effective in up to 75% of cases. However, this procedure is so painful for the patient that it normally requires epidural anesthesia, and it carries a small risk of fetal intolerance, excessive cord traction, or placental abruption necessitating an emergency (“crash”) early-term cesarean delivery.

The other option is a scheduled Caesarean section, which is what is ultimately performed in most cases. This approach minimizes the risk of an emergency cesarean section, but many patients elect to undergo an ECV in an attempt to have a vaginal delivery. Of note, a single cesarean delivery for breech presentation does NOT preclude future VBAC.

If a patient goes into spontaneous labor with an infant in breech position, a cesarean section should be performed.

Complications

Complications of breech position include:

Cord prolapse

Head entrapment

Fetal hypoxia

Abruptio placentae

Birth trauma

Increased risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip

Premature Rupture

Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) refers to spontaneous rupture of the amniotic sac with spillage of amniotic fluid before the onset of labor.

Rupture of membranes before 37 weeks is termed preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) and is a common cause of preterm labor.

If the rupture occurs for longer than 18 hours before delivery, it is described as prolonged rupture of membranes.

Risk factors associated with PROM include:

Vaginal or cervical infection

Cervical incompetence

Poor maternal nutrition

Prior PROM

Diagnosis

PROM presents with loss of amniotic fluid from the vagina and the amniotic fluid may be seen pooling in the vagina on visual examination.

Internal manual examination should not be performed in cases of PROM because of an increased risk of introducing infection into the vaginal canal. Vaginal fluid should be cultured to detect infection.

Sterile speculum exam (performed without gel) can detect pooling of fluid in the vagina.

Nitrazine paper can be used to detect amniotic fluid in vaginal fluid, which will turn blue upon exposure. The test measures acidity. Normally the vaginal fluid is acidic (pH 3.8 to 4.2), but amniotic fluid is neutral (pH 7.0 to 7.3) turning the nitrazine paper blue,

Microscopic examination of vaginal fluid will show “ferning” since amniotic fluid produces a fern like pattern when swabbed onto a glass slide and allowed to dry to 10 minutes. This is in contrast to the dried cervical mucus, which produces a thick and wide arborization.

Ultrasound can be used to confirm oligohydramnios, to assess the volume of residual amniotic fluid and to determine the fetal position.

Management

In treating PPROM, the risk of chorioamnionitis must be balanced with the risk of prematurity.

If PPROM occurs at <32 weeks’ gestation, corticosteroids should be used to hasten fetal lung maturity. Antibiotics should be give9n prophylactically for group B strep. Labor should be induced once amniotic fluid analysis indicates fetal lung maturity.

(At this stage, a decision must be made about the management of this patient. If the fetal status is reassuring, she can be admitted to the antepartum service for latency antibiotics, antenatal corticosteroids, and further monitoring. If, however, the fetus shows evidence of severe distress, immediate delivery may be indicated to prevent intrauterine demise. In order to determine which of these two course is most appropriate, a fetal non-stress test should be performed.)

If PPROM occurs between 32 to 34 weeks’ gestation, amniotic fluid analysis is performed to determine fetal lung maturity. Labor should be induced if lung maturity has occurred, but if not corticosteroids and antibiotics should be administered until they mature.

If PPROM occurs>34 weeks’ gestation, antibiotics should be administered and delivery should be induced.

Chorioamnionitis is an infection of the membranes and amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus. It is the most common precursor of neonatal sepsis.

The presentation of chorioamnionitis includes:

ROM

Maternal fever

Elevated maternal white count

Uterine tenderness in the absence of other known source of fever such as URI or UTI

Fetal tachycardia

Suspected chorioamnionitis should be treated with ampicillin, gentamicin, and clindamycin. Delivery should also be hastened.

Prolapsed Umbilical Cord

Umbilical cord prolapse a rare emergency where the umbilical cord descends alongside the fetus, or beyond the presenting part of the fetus. It is a life threatening condition to the fetus as blood flow through the umbilical vessels can be compromised, disrupting fetal oxygenation.

Overt prolapse is the most common scenario, which refers to protrusion of the cord in advance of the fetal presenting part.

Occult prolapse is where the umbilical cord descends alongside the fetus, but does not descend past the presenting part.

Risk factors for umbilical cord prolapse are generally not modifiable and include:

Fetal malpresentation

Prematurity/low birth weight

Multiple gestation

Multiparity

Rupture of membranes with the fetus at -2 station or higher

Polyhydramnios

Management

The management of umbilical cord prolapse involves prompt delivery to prevent fetal compromise or death due to compression of the cord. Cesarean delivery is the optimal method of delivery.

Methods of reducing pressure on the umbilical cord include:

Manual elevation of the fetal presenting part

Filling the mother's bladder using a foley catheter, which causes elevation of the fetal presenting part

Umbilical cord prolapse is first recognized when there is a sudden, severe prolonged fetal bradycardia which can show severe variable decelerations after a previously normal fetal tracing.

Umbilical cord prolapse should be suspected if abnormal tracing develops after the membranes rupture.

In an overt prolapse, the umbilical cord may be palpable upon vaginal examination as it protrudes into the vagina.

Conditions that should be ruled out when fetal bradycardia presents include:

Maternal hypotension

Placental abruption

Uterine rupture

Vasa previa

Shoulder Dystocia

A shoulder dystocia occurs when the infant’s head delivers, but not the shoulders and the rest of the body, requiring more than gentle traction to enable delivery of the shoulders.

The shoulders usually enter the pelvis at an oblique angle so that as the fetus is rotated the shoulders can deliver without impaction.

In shoulder dystocia the anterior shoulder of the fetus is typically impacted behind the mother’s pubic symphysis.

Risk factors associated with shoulder dystocia include:

Maternal diabetes (leading to infants with their body fat distributed disproportionately in the upper torso)

Maternal obesity

Postterm pregnancies

Fetal macrosomia

However, most occur in the absence of risk factors.

The diagnosis is a subjective clinical one, and is usually made in the second stage of labor when the head has delivered, but the delivery of the shoulders is delayed.

The "turtle" sign is when the fetal head retracts back against the perineum after delivery of the head but before delivery of the body.

It is highly suggestive of shoulder dystocia.

Management

The goals of managing shoulder dystocia are to safely deliver the infant without causing asphyxia from cord compression or peripheral neurological damage as a result of trauma.

Managing shoulder dystocia requires an experienced team and includes the following maneuvers:

McRobert’s maneuver (maternal thigh flexion)

Wood’s corkscrew maneuver (rotation of the infant to dislodge the shoulder)

Delivering the posterior arm

If these maneuvers do not work, the fetal clavicle may be fractured to ease delivery or a Zavanelli maneuver (the infant’s head is pushed back into the uterus) can be performed in preparation for cesarean delivery.

Complications associated with shoulder dystocia include:

Clavicle and humerus fractures

Erb palsy

Phrenic nerve palsy

Hypoxic brain injury

Death

Last updated