06 GI

Stomach

PUD

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) refers to a defect within the mucosal wall of the duodenum and stomach that typically results in recurrent episodes of epigastric pain.

The duodenum and stomach both contain a mucosal lining that protects the underlying cells from its acidic environment. Epithelial cells line these structures and secrete bicarbonate to help buffer the acid to prevent mucosal damage. Peptic ulcer disease results when these protective barriers are disrupted.

Peptic ulcer disease may be caused by any of the following:

H. pylori infection

Drugs (NSAIDs, SSRI)

Alcohol

S moking

S evere physiologic stress (burns, head trauma, surgery)

Hypersecretion of acid

H. pylori infection and NSAID use are the two most common causes of peptic ulcer disease. H. pylori is a gram-negative bacteria that releases enzymes which increase acid secretion and inhibit bicarbonate production within the stomach, resulting in inflammation and ulceration.

Patients with peptic ulcer disease typically present with recurrent episodes of epigastric pain which they describe as a dull, gnawing, burning sensation.

The pain associated with peptic ulcer disease is often worsened by eating in gastric ulcers, but relieved with eating in duodenal ulcers. Weight gain can occur with duodenal ulcers since their pain improves with eating, while weight loss is typically seen in gastric ulcers due to increased pain with food.

Other possible manifestations of peptic ulcer disease include:

Belching

Bloating

Heartburn

Nausea and vomiting

There are some symptoms however that require immediate gastroenterology referral, known as alarm symptoms:

Unexplained weight loss

Early satiety

Hematemesis (vomiting blood)

Melena (dark, tarry stools)

Hematochezia (bloody stools)

Family history of gastrointestinal cancer

Painful or difficulty swallowing

Diagnosis

Upper endoscopy is the diagnostic test of choice in evaluating patients with peptic ulcer disease. Endoscopy allows for the direct visualization of gastric and duodenal ulcers, biopsies to rule out malignant lesions and allows for the detection of H. pylori infections.

H. pylori testing should be performed on all patients suspected of having PUD. There are many ways in which H. pylori can be tested:

Mucosal biopsy (most accurate)

Rapid urease testing

Urease breath test

Fecal H. pylori antigen testing

H. pylori serum antibody testing. This test is not able to differentiate between past and active infections and therefore has minimal diagnostic utility.

Radiographic studies are usually not helpful in diagnosing PUD, unless a perforation has occurred which would show free air below the diaphragm on a chest x-ray.

PUD may result in complications such as:

Bleeding (hematemesis, melena, hematochezia)

Perforation

Death

The most common complication from peptic ulcer disease is hemorrhage, not perforation. Bleeding results when ulcers erode the vasculature within the walls of the gastric and duodenal mucosa.

Treatment

Treatment of PUD typically consists of:

Eradicating H. pylori infections with triple therapy antibiotics

Avoiding exacerbating factors (NSAIDS, alcohol, smoking)

Proton pump inhibitors (PPI)

Acute bleeding ulcers and perforation require surgical intervention.

First-line therapy for H. pylori infection includes:

Proton pump inhibitor (e.g. omeprazole, lansoprazole)

Amoxicillin

Clarithromycin

In penicillin allergic patients, the amoxicillin is replaced with metronidazole.

Bleeding ulcers require endoscopic intervention to locate the source, then they can either be ligated with a suture or cauterized to control the bleeding.

Surgery is indicated once an ulcer has perforated the bowel wall. Duodenal perforation is typically repaired with an omental (Graham) patch, where a piece of omentum is sutured over the perforation. Gastric perforation is repaired by partially resecting the damaged gastric wall--an omental patch may be used here as well.

Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric cancer is 90% adenocarcinoma, and is further divided into intestinal and diffuse subtypes.

Intestinal gastric adenocarcinoma is more common in older patients and has a better prognosis. It also has a higher association with H. pylori infection and chronic gastritis than the diffuse type.

Diffuse gastric adenocarcinoma is more common in younger and female patients, and is the most common subtype in the United States.

Risk factors include GAS MASH:

Gastrectomy in the past for gastric ulcer Anemia (pernicious) and Achlorhydria Smoking

Menetrier’s disease A blood group Smoked fish or other nitrates H. pylori

Patients often present with:

Decreased appetite

Weight loss

Abdominal discomfort or pain

Nausea

Vomiting

In patients with the sudden dermatologic onset of seborrheic keratoses, consider an underlying gastric malignancy. This paraneoplastic phenomenon is known as the Leser–Trélat syndrome.

Dysphagia may occur with obstruction of the gastroesophageal junction.

Diagnosis is confirmed by upper endoscopy with biopsy.

Fecal occult blood test is often positive, with or without a history of melena.

CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis (in women) should be performed to evaluate for metastatic spread or a primary tumor.

Helicobacter pylori testing should also be done.

The classic physical exam findings for metastatic disease are supraclavicular (Virchow’s node) or periumbilical nodes (Sister Mary Joseph’s node).

Many gastric cancers are found in their later stages when metastases have already occurred.

Gastric cancer often metastasizes to the ovaries (Krukenberg’s tumor). Rectal (Blumer’s shelf) metastases are palpable on digital rectal exam.

Resection with lymph node dissection is preferred, with chemotherapy and radiation except in cases of early disease.

Palliative radiation is used in non-resectable cases.

Gastritis

Gastritis is defined as an inflammation and erosion of the gastric lining. The mucosa lining the stomach helps protect it from offending agents and when the mucosa becomes injured or damaged, it is unable to protect itself from further injury.

Gastritis most commonly occurs with:

NSAIDs (aspirin, ibuprofen)

Alcohol abuse

H. pylori infections

Other risks include portal hypertension, severe stress (burns, trauma, sepsis), and autoimmune disease.

Patients with gastritis will typically complain of a gnawing or burning sensation within their epigastric region, which may or may not be accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

Upper endoscopy with mucosal biopsy is the diagnostic modality of choice for gastritis. Endoscopy allows direct visualization of mucosal damage and biopsy helps the diagnostician determine the etiology.

Stool antigen and urea breath test are used to help rule out H. pylori infection.

Imaging such as a double-contrast barium study can help determine the extent of gastric erosions.

Gastritis may result in:

Anemia

Hematemesis

Ulcers

Perforation

Strictures

Weight loss

Gastric cancer

Treatment of gastritis includes the discontinuation of offending agents (NSAIDs, aspirin, alcohol), and administration of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Consider triple therapy (PPI + amoxicillin + clarithromycin) if H. pylori is found to be the cause of gastritis.

Antacids

Antacids directly neutralize the stomach acidity.

Side effects of antacids may include:

Constipation

Nausea

Diarrhea

H2 antagonists block histamine receptors, preventing histamine mediated acid release from parietal cells.

Side effects of H2 blockers include:

Headache

Diarrhea

Thrombocytopenia (rarely)

Cimetidine can cause gynecomastia and impotence

PPIs block the parietal cell H+/K+ ATPase.

Omeprazole is an inhibitor of the cytochrome P-450 system.

PPIs may also cause:

Rebound hyperacidity

Enteric and respiratory infections

Bone fractures (due to decreased calcium absorption)

Acute interstitial nephritis

Nutritional deficiencies (due to decreased B12 and magnesium absorption)

Urea breath testing for the diagnosis of H. pylori in patients on PPIs may yield false-negative results since PPIs can suppress H. pylori. Thus, patients should discontinue PPIs for a minimum of 2 weeks prior to undergoing a urea breath test.

Lactose Intolerance

Lactose intolerance is a malabsorption syndrome resulting from a deficiency in lactase. This leads to the inability to absorb lactose from the diet. It may also be secondary to other disease processes such as Crohn's disease or overgrowth of intestinal flora.

Lactase is normally located in the brush border of the enterocytes of the intestinal villi.

Deficiency of lactase may be primary or secondary:

Primary deficiency is the most common, in which lactase production decreases over time.

Secondary deficiency results from injury to the small intestine, such as in Crohn's disease, small bowel surgery, or infection.

Congenital absence of lactase is genetically linked and is very rare.

Symptoms are a result of an increased osmotic gradient in the gut. Following consumption of dairy products, patients may present with:

Abdominal pain

Bloating

Flatulence

Osmotic diarrhea

Vomiting (particularly in adolescents)

Stools of patients with lactose intolerance are usually bulky, frothy, and watery.

Borborygmi (rumbling noises made by gas and fluid in the intestines) may be audible on physical examination and to the patient.

Diagnosis is confirmed by either a lactose absorption test (positive test will reveal minimal increase in serum glucose after ingesting lactose) or a lactose breath hydrogen test.

The mainstay of treatment is a lactose-free or lactose-restricted diet. Patients must receive adequate amounts of other nutrients such as vitamins, protein, and fat. Lactase enzyme replacement is an option that may benefit some patients.

Gastroenteritis

The most common presentation for viral gastroenteritis is:

Diffuse watery diarrhea

Mild fever

Malaise

Viral gastroenteritis may result in severe dehydration, hypotension, and syncope.

Coxsackie B infections may result in:

Severe dehydration

Sepsis

Myocarditis

Pericarditis

Aseptic meningitis

Viral gastroenteritis is usually self-limited and typically treated with supportive therapy (e.g. fluid and electrolyte replacement). Antiemetics (e.g. ondansetron) and antimotility agents (e.g. loperamide) may be incorporated if vomiting and diarrhea become severe.

Viral gastroenteritis is inflammation of the stomach and intestines (commonly called the "stomach flu"). Four viruses commonly implicated in viral gastroenteritis include:

Norovirus

Echovirus

Rotavirus

Coxsackie virus

Norovirus, previously referred to as the Norwalk virus, is the most common cause of viral gastroenteritis in adults. The virus is endemic in the winter months and most commonly spread via the fecal-oral route.

Infected people tend to contaminate food and other surfaces by improper hand washing. Outbreaks commonly occur in restaurants, military facilities, healthcare facilities, schools, and cruise ships.

ECHO (Enteric Cytopathic Human Orphan) viruses are members of the Enterovirus genus and are found within the gastrointestinal tract. The echovirus typically infects via the fecal-oral route and is a common cause of gastroenteritis, aseptic meningitis, and myocarditis in the summer and fall.

Coxsackie viruses (A and B) are members of the Enterovirus genus and are primarily transmitted via fecal-oral route and by respiratory droplets. Type A is responsible for herpangina, conjunctivitis, and hand-foot-and-mouth disease, while type B is responsible for gastrointestinal inflammation.

Rotavirus most severely affects children under the age of 5 and is a vaccine-preventable cause of illness. It typically strikes during the winter months (December-May), and is usually acquired in settings such as daycare.

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the most sensitive and specific diagnostic method for Norovirus and echo virus, but it is not typically required.

Testing for fecal leukocytes and fecal blood is important in ruling out invasive diarrheal infections.

The best diagnostic modality for Coxsackie B viral infections is viral culture. Samples are typically taken from stool and rectal swabs, but can also be isolated from the oropharynx.

Liver Disease

Budd-Chiari

Budd-Chiari syndrome (or hepatic vein thrombosis) is defined as any thrombotic or obstructive process, which inhibits the outflow of blood within the hepatic venous system.

Most patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome have some underlying thrombotic risk factor. Some of the most common risk factors include:

Myeloproliferative disease (e.g. polycythemia vera)

Usage of oral contraceptives

Pregnancy

Malignancy

Inherited hypercoagulable diseases

The most common presentation is:

Hepatosplenomegaly

Ascites

Abdominal pain

Renal impairment

As the disease progresses signs of liver failure (eg jaundice, encephalopathy) and portal hypertension (eg ascites, hematemesis) become more prominent.

Venography is the gold standard for diagnosis, but is typically only used when initial non-invasive diagnostic tests (e.g. ultrasound, CT, MRI) are negative and there is a high suspicion for the disease.

Budd-Chiari syndrome may result in long term complications such as:

Liver failure

Renal failure

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Portal hypertension (e.g. hematemesis)

Note: A way to remember these are that they are similar findings to those seen in a patient with cirrhosis.

Treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome depends on the clinical presentation of the patient and extent of thrombosis. The most common form of treatment includes anticoagulation therapy with heparin and warfarin along with venous stenting.

Diuretics such as spironolactone and furosemide are incorporated to help with ascites and fluid overload.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is another procedure used to help decompress the liver when portal hypertension is present. Liver transplant is a last resort.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic disease of unknown etiology, which is characterized by:

Circulating autoantibodies

Hepatocellular inflammation

Fibrosis

Risk factors for autoimmune hepatitis include:

Caucasian race of northern European ancestry

Female gender

Acute hepatitis A and B infections

Patients with HLA haplotypes DR3 and DR4

Symptoms

Symptoms can vary widely in patients with AIH, and may include:

Asymptomatic

Fulminant hepatic failure

RUQ pain

Jaundice

Fatigue

Hepatosplenomegaly

Ascites

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis is generally based upon characteristic clinical and serological features, but liver biopsy may be required to confirm the diagnosis.

Other helpful serological studies include:

Anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA)

Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA)

Anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody (anti-LKM)

IgG immunoglobulins

Serum aminotransferase (AST and ALT)

Bilirubin

Alkaline phosphatase

AIH may result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and eventual fulminant hepatic failure.

Treatment

The best initial therapy for AIH is prednisone and azathioprine.

Liver function tests are performed weekly for the first 6-8 weeks, then every 2-3 months to monitor therapy response.

Ischemic Hepatitis

Ischemic hepatitis is caused by a decrease in blood flow leading to diffuse, hypoxic liver injury.

Risk factors for ischemic hepatitis include:

Shock

Congestive heart failure

Blood loss

Hepatic artery thrombosis

Portal vein thrombosis

Sickle cell anemia

Any cause of hemodynamic instability

Patients with ischemic hepatitis typically present with:

Signs of hemodynamic instability

Nausea

Vomiting

Right upper quadrant pain

Ischemic hepatitis is best diagnosed clinically by:

A sudden increase in liver enzymes (AST and ALT greater than 1000 IU/L)

Early, rapid rise of lactate dehydrogenase

Recent hypotensive event

Other end organ damage

Ischemic hepatitis is typically managed by treating the underlying cause of the hemodynamic instability.

If left untreated, ischemic hepatitis may cause:

Encephalopathy

Jaundice

Acute hepatic failure

Hepatopulmonary syndrome

Acetaminophen overdose

The most significant effect of acetaminophen overdose is hepatotoxicity. Acetaminophen is primarily metabolized into N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), a highly reactive, toxic intermediate. At toxic doses, the hepatic glutathione pathway is saturated, and NAPQI reacts with cysteine groups on hepatic macromolecules leading to oxidative injury and hepatocellular necrosis.

Patients with acute liver injury due to acetaminophen toxicity can present along a spectrum of severity:

Within 1 day: asymptomatic or mild nausea/vomiting

After 24 hours: abdominal pain, increasing severity of other symptoms

In the most severe cases, hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity precedes multiorgan failure and eventual death

Cerebral edema is a potential complication of ALF that may lead to coma and brain stem herniation, and is the most common cause of death.

Acetaminophen is the most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States.

Acute liver failure is defined as the development of hepatic injury in a patient without cirrhosis or preexisting liver disease. All 3 of the following criteria are required for the diagnosis of acute liver failure:

Elevated aminotransferases

Hepatic encephalopathy

Prolonged PT (INR ≥1.5)

The diagnosis of acetaminophen toxicity relies on the history as most patients are initially asymptomatic.

Acetaminophen levels can be checked to determine the extent of overdose.

Management

Both liver and kidney function should be monitored closely by checking:

Transaminases

Coagulation studies

BUN

Creatinine

The antidote to acetaminophen overdose, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), is believed to regenerate hepatic glutathione stores, which helps with the elimination of free radicals.

NAC is most effective when administered within the first 8 hours of overdose.

If patients present within 4 hours of acetaminophen ingestion, activated charcoal can be used to prevent the absorption of acetaminophen in the gut.

In ALF due to acetaminophen toxicity, liver transplantation is firmly indicated in patients with grade III or IV hepatic encephalopathy, PT >100 seconds, and serum creatinine >3.4 mg/dL (as in this patient). One-year survival following liver transplantation for ALF is approximately 80%.

Fulminant Liver Failure

Liver failure occurs when the liver is unable to fulfill its synthetic and metabolic functions, resulting in systemic symptoms or failure of other organ systems.

Acute liver failure occurs within weeks or monthsof severe acute liver injury, such as acetaminophen poisoning.

Chronic liver failure or cirrhosis is due to repeated liver injury, most commonly due to hepatitis C.

Fulminant hepatic failure is the rapid onset of acute liver failure and hepatic encephalopathy within 2 months of symptom onset.

Management is aimed at supportive care, stabilizing the patient, and treating the complicationsof their liver injury.

Causes of fulminant hepatic failure include:

Toxins(e.g. acetaminophen toxicity)

Viruses (e.g. Hepatitis B)

Ischemia

Metabolic disorders

Symptoms of liver failure can be vague or multi-systemic, and include:

Weight loss

Anorexia

Weakness

Jaundice and scleral icterus

Palmar erythema

Spider nevi

Gynecomastia

Hepatic encephalopathy (manifested as asterixis, confusion)

Coagulopathy

Anemia

Lower extremity edema

Specific symptoms are generally the result of either metabolic compromise or synthetic compromise of the liver. Metabolic compromise can lead to:

Hyperbilirubinemia

Jaundice

Hyperestrogen state (palmar erythema, spider angioma, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy)

Synthetic compromise may lead to:

Hypoalbuminemia and edema

Coagulopathy

Management of liver failure focuses on the preservation of remaining function and avoidance of further injury.

Medications that can be used for the complications of liver failure include:

Lactulose and rifaximin for hepatic encephalopathy

Cefotaxime for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Bile acid sequestrants(i.e. colestipol and cholestyramine, etc) for jaundice causing pruritis

Salt restriction and diuretics to prevent volume overload from ascites

Additional ways liver failure can be managed include:

Avoidance of hepatotoxins, especially drugs cleared by the liver

High protein diet and B vitamins to support metabolic function

The most serious complication of liver failure is death. This is typically due to one of the following:

Progressive liver failure

Complications of portal hypertension such as rupture of esophageal varices or hepatic encephalopathy

Development of hepatocellular carcinoma

Transplantis the only curative treatment for liver failure.

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is a diffuse, irreversible hepatic process characterized by fibrosis, regenerating nodules, and distortion of the normal hepatic parenchyma.

Some common causes of cirrhosis within the U.S. are:

Hepatitis C (most common)

Alcoholic liver disease (2nd most common)

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

Hepatitis B

An acute/chronic disease process injures the liver cells, which then undergo inflammatory changes leading to necrosis and fibrosis. Sub-endothelial fibrosis leads to the impairment of normal hepatic functionality.

Less common causes of cirrhosis include:

Autoimmune hepatitis

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Hemochromatosis

Wilson’s disease

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Drug induced causes

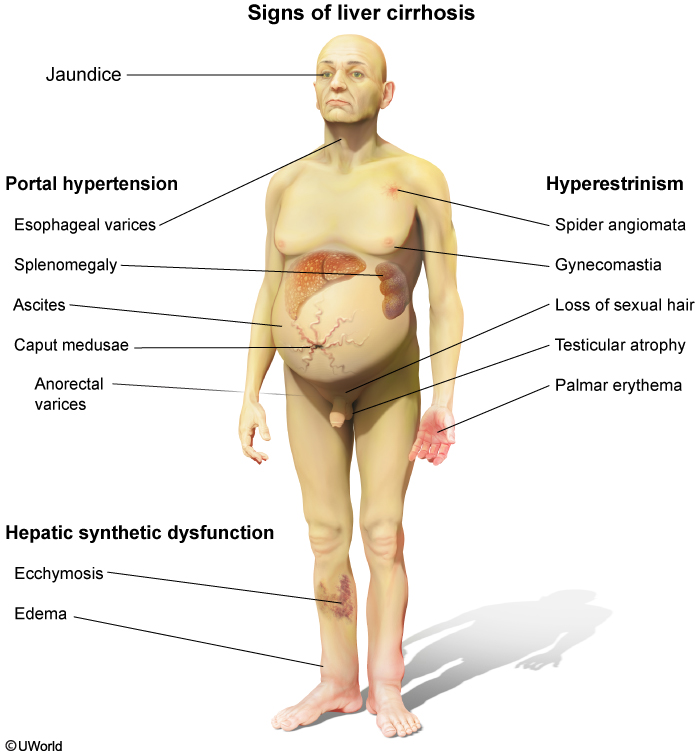

Patients with cirrhosis present with several physical findings including:

Jaundice

Palmar erythema

Spider angiomata

Petechiae

Ascites

Hepatic encephalopathy

Gynecomastia

Caput medusa

Asterixis

Physical exam of the liver may reveal an enlarged, normal, or small sized liver. If palpable, cirrhosis causes it to have a firm and nodular consistency.

Compensated cirrhosis patients will classically present with nonspecific symptoms such as:

Fatigue

Weight loss

Weakness

Decompensated cirrhosis patients may present with more specific symptoms, including:

Confusion

Ascites

Edema

Pruritus

Hematemesis

Melena

Diagnosis

The gold standard for diagnosing cirrhosis is a liver biopsy, however it is not necessary if clinical, laboratory and radiographic studies suggest cirrhosis. The pathologic features of cirrhosis include: the presence of fibrosis, regenerating hepatic nodules, and decreased number of septa.

Ultrasound is the most common imaging in the evaluation of cirrhosis, as it allows the physician to assess the contour of the liver, impedance of blood flow, and amount of ascites within the abdomen. Other helpful imaging modalities include CT abdomen, radiographs (chest and kidney-ureter-bladder views to assess for secondary complications of cirrhosis), and MRI.

In the work up of cirrhosis, there are several laboratory tests that are required to assess the functionality of the liver. Common laboratory tests include:

Bilirubin

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT)

Albumin

Prothrombin time (prolonged in cirrhosis)

Platelet count (low in cirrhosis)

Electrolyte panel (low sodium)

Patients with cirrhosis are susceptible to several complications including:

Ascites

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Variceal hemorrhage

Hepatopulmonary syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome

Portal vein thrombosis

Cardiomyopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy

Cirrhosis (especially due to alcoholic liver disease or hemochromatosis) can cause hypogonadism due to primary gonadal injury or hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction. Cirrhosis is also associated with elevated circulating levels of estradiol due to increased conversion from androgens. Findings due to excess estrogen include telangiectasias, palmar erythema, testicular atrophy, and gynecomastia (usually bilateral but can be unilateral).

In addition, the liver produces serum binding proteins for thyroid hormones (eg, thyroxine-binding globulin, transthyretin, albumin, lipoproteins). Cirrhosis leads to decreased synthesis of these proteins, which lowers the total triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) in circulation; however, free T3 and T4 levels are unchanged, and TSH will be normal, reflecting a euthyroid status.

Portal hypertension (PHT) is the underlying cause of most of the complications associated with cirrhosis. As the pressure becomes severely elevated venous blood begins to back up into the esophageal and gastric veins, resulting in varices and even ascites.

Treatment

The primary focus in treating cirrhosis is treatment of the underlying disease process. This involves managing toxic insults and preventing serious secondary complications.

Lactulose is used during acute hepatic encephalopathy. Lactulose prevents the absorption of ammonia. It is theorized that ammonia and other neurotoxic metabolites build up in the bloodstream and gain entry into the brain secondary to liver failure.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a procedure performed when patients present with severe portal hypertension. This procedure creates a new route for blood to pass through the damaged liver.

Beta blockers are used to help keep the pressure low when a patient presents with esophageal or gastric varices.

Ultimately, transplantation is the only cure for a cirrhotic liver. Before transplantation is considered, the patient’s prognosis is calculated using either the Child-Pugh classification or the Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD).

Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis is the abnormal accumulation of iron in parenchymal organs, leading to organ toxicity.

Primary (hereditary) hemochromatosis is a result of autosomal recessive inheritance in a mutation of the HFE gene on chromosome 6. This leads to excessive iron absorption and progressive iron overload.

The secondary form of hemochromatosis may occur in the following situations:

Conditions resulting in ineffective erythropoiesis (e.g. thalassemia, sideroblastic anemia)

Multiple transfusions

Chronic liver disease

Hemochromatosis is associated with the HLA-A3 haplotype.

Onset is in adult years (30-50 yrs) with the classic triad of:

Micronodular cirrhosis (deposition of hemosiderin in the liver)

Diabetes mellitus(iron accumulation in pancreas and beta cell damage)

Bronze skin pigmentation(secondary to hemosiderin and melanin deposition)

Other symptoms may include:

Arthropathy(40-60% of patients, may be the first sign of disease)

Chondrocalcinosis

2nd and 3rd metacarpophalangeal (MCP) arthritis

Dilated or restrictive cardiomyopathy (iron accumulation in the myocardium)

Amenorrhea, impotence, hypogonadism

The best screening test is transferrin saturation, while serum ferritin is used to follow therapy. Both values are elevated.

Iron studies will reveal:

Increased serum iron

Increased serum ferritin

D ecrease in total iron binding capacity

Due to the abundance of iron, transferrin % saturation is increased

If performed, liver biopsy reveals high iron content seen with Prussian blue staining.

Genetic testing for HFE gene mutations is pivotal for diagnosis.

Complications include:

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Cirrhosis

Congestive heart failure

Cardiac arrhythmias

Hypogonadism

Arthropathy

Diabetes mellitus

Thyroid dysfunction

Sepsis

Medical treatment for hereditary hemochromatosis includes repeated phlebotomy (preferred) or iron chelating agents (e.g. deferoxamine, deferiprone, deferasirox).

Surgery is indicated for end-stage liver disease (transplant) and severe arthropathy (arthroplasty).

Wilson Disease

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive disordercharacterized by impaired biliary copper secretion, leading to copper deposition in the liver, brain, eyes, and other tissues.

Wilson disease usually presents in patients < 30 years of age.

In contrast, hereditary hemochromatosis usually presents after age 40 in males and even later in females.

ATP7B encodes a transmembrane copper transporter. Mutation of this gene in Wilson disease causes:

Decreased copper secretion into bile

Decreased copper incorporation into ceruloplasmin

Decreased ceruloplasmin secretion into blood

The defect involves a copper transporting protein (ATP7B) and is linked to chromosome 13.

Physical exam findings in a patient with Wilson disease may include:

Kayser-Fleischer rings in the cornea (pathognomonic)

Hepatomegaly

Parkinsonian tremor

Slit-lamp examination of patients with Wilson disease classically reveals Kayser-Fleischer rings, which are green/brown deposits of copper in the Descemet membrane of the cornea.

Patients with Wilson disease often present with movement disorders that resemble Parkinson disease due to copper deposition in the basal ganglia, in particular the putamen. Copper deposition in other parts of the CNS can cause dementia, dyskinesia, and dysarthria.

Liver symptoms may include:

Asterixis

Jaundice

Mental status changes (secondary to hepatic encephalopathy)

Acute hepatitis

Portal hypertension

Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia can occur in Wilson disease since copper is toxic to red blood cell membranes.

Copper deposition in the joints causes degenerative arthritis, typically affecting the spine and large joints.

Wilson disease is diagnosed in the following ways:

Neurologic symptoms + Kayser-Fleischer rings + ceruloplasmin <20 mg/dL

OR

Isolated liver disease + hepatic copper concentration >250 mcg/g dry weight liver + low serum ceruloplasmin

If neurologic symptoms and Keyser-Fleischer rings are absent, liver biopsy and quantitative copper determination is necessary for diagnosis.

Genetic testing is not required for diagnosis. Genetic studies are useful for screening family members of affected patients in whom there has been a previously identified mutation.

Patients with Wilson's disease will have decreased serum ceruloplasmin with elevated free copper but decreased total copper.

The mainstay of treatment for Wilson disease is pharmacologic treatment with chelating agents, including zinc and D-penicillamine.

Medications used to treat the other symptoms of Wilson disease include:

Anticholinergics, GABA antagonists, and levodopa(for treatment of parkinsonism)

Antiepileptics (to treat seizures)

Neuroleptics (to treat psychosis and other psychiatric symptoms)

Lactulose (to treat hepatic encephalopathy)

Orthotopic liver transplantation is curative for Wilson disease and may be indicated in the case of worsening hepatic function or progression of disease.

Complications of Wilson disease include:

Cirrhosis

Liver failure

Persistent neurological deficits (Parkinsonian symptoms, dementia)

Psychiatric problems (personality changes, depression, bipolar disorder, psychosis)

Amino aciduria

Nephrocalcinosis

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy occurs when ammonia clearance is compromised (due to chronic liver dysfunction) and consequently builds up and crosses into the CNS.

Patients present with altered mental status(e.g. confusion, stupor, coma) and signs of chronic liver disease (e.g. asterixis).

Diagnosis is based on serum ammonia levels, and evaluating liver function via the following:

AST

ALT

Albumin

Bilirubin

Prothrombin time

Partial thromboplastin time

Treatment is aimed at ammonia reduction, which can be achieved through:

Lactulose,which prevents the absorption of ammonia

Antibiotics (i.e. rifaximin or neomycin) that decrease ammonia production by gut bacteria

Diet adequate with protein and energy (low protein diet, though once considered beneficial, has been shown to be detrimental in most patients as they are already malnourished and require sufficient protein to maintain a healthy body weight)

Branched-chain amino acid and probiotic supplementation, if indicated

Patients with advanced liver disease should be evaluated for transplant as this is the only curative measure.

Hepatorenal Syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome is the development of renal failure in patients with acute or chronic liver disease. Hepatorenal syndrome most often occurs in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and severe alcoholic hepatitis, but can occur in anyone with severe liver disease.

In the setting of severe cirrhosis of the liver, portal hypertension induces the aberrant production of the vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) within the splanchnic circulation. A NO-mediated reduction in vascular resistance within the splanchnic circulation results in a fall in systemic vascular resistance, which causes renal hypoperfusion and triggers the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone and sympathetic nervous systems.

These compensatory neurohormonal responses further exacerbate renal hypoperfusion and fluid retention.

Patients with hepatorenal syndrome present with clinical symptoms of kidney failure such as:

Azotemia

Oliguria

Hyponatremia

Hypotension

Diagnosing hepatorenal syndrome is one of exclusion. Other causes of acute kidney injury such as glomerulonephritis, ATN and prerenal disease must be ruled out before a diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome can be made.

Patients with hepatorenal syndrome have laboratory findings consistent with prerenal azotemia:

Low urine sodium (<10 mEq/L)

FeNa <1%

BUN:Cr ratio >20:1

Serum Cr >1.5

Hepatorenal syndrome may be distinguished from prerenal azotemia through a fluid challenge.

In prerenal azotemia, the patient's condition will improve upon administration of a fluid bolus.

In hepatorenal syndrome, fluid bolus administration will exacerbate the condition through initially expanding the intravascular space, and subsequently expanding the "third space".

Hepatorenal syndrome is considered a functional renal failure since the kidneys are morphologically and histologically NORMAL. Therefore, the definitive treatment for patients with hepatorenal syndrome is liver transplant rather than kidney transplant.

Treatment

Hepatorenal syndrome is best managed with vasoconstrictors such as:

Terlipressin

Norepinephrine

Octreotide

Midodrine

Note: Midodrine is a systemic vasoconstrictor, and octreotide inhibits vasodilator release. When given in combination with albumin, this therapy improves renal hemodynamics.

Patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome have hypoxemia and dyspnea in the presence of long standing liver disease.

Two exam findings specific to patients with hepatopulmonary syndrome are:

Orthodeoxia is hypoxia in an upright or sitting position that improves when returning to a recumbent position.

Platypnea is increased dyspnea while walking in an upright position that is relieved when returning to a recumbent position.

Alcoholic Liver Disease

Alcoholic liver disease is a disorder that causes progressive liver inflammation and damage from excessive alcohol intake.

The progression of liver disease in alcoholics if untreated goes from fatty steatosis, to alcoholic hepatitis to eventually liver cirrhosis/fibrosis. If the patient receives treatment, fatty steatosis and alcoholic hepatitis are usually reversible. Changes associated with cirrhosis and liver fibrosis, however, are not.

Most patients with alcoholic liver disease will experience non-specific symptoms, such as fatigue, malaise, and nausea. Patients who have cirrhosis due to alcohol liver disease can develop any of the following conditions:

Jaundice

Ascites

Esophageal varices

Spider angiomata

Gynecomastia

Testicular atrophy

Dupuytren contracture

Diagnosis of alcoholic liver disease is made after excluding other causes of cirrhosis or fatty liver, and includes:

Detailed history about alcohol use, including amount and frequency

Physical examto look for stigmata of chronic liver disease

Blood work to assess liver synthetic function and inflammation (including CBC, albumin, AST/ALT, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, coagulation studies)

Ultrasound of the liver

A liver biopsy may be required if diagnosis can't be reached via noninvasive methods. Biopsy may reveal eosinophilic hyaline inclusion bodies (Mallory bodies), steatosis (fatty deposition), and fibrosis.

A ratio of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) greater or equal to 2:1 is highly associated with alcoholic liver disease. Other causes of liver disease rarely produce similar elevations in liver enzymes.

Other laboratory tests that are commonly elevated in alcoholic liver disease include:

Bilirubin

Alkaline phosphatase

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT)

PT/INR

MCV

Alcoholic liver disease may result in:

Cirrhotic complications (eg jaundice, hematemesis, portal hypertension, encephalopathy)

Liver failure

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Death

Abstinence is the main focus in treating patients without end stage liver disease. Supportive care in the way of proper nutrition and immunization (Hep A, Hep B) prevent further hepatic damage.

Medications such as Disulfiram (Antabuse) can assist patients in the abstinence process. Disulfiram works by inhibiting the action of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase responsible for the conversion of acetaldehyde to acetic acid in the second step of the metabolism of ethanol. Increased levels of acetaldehyde causes flushing, nausea and vomiting when alcohol is consumed.

Drug Induced Hepatitis

The liver is especially vulnerable to drug toxicity as it metabolizes nearly all medications and herbal supplements via the cytochrome P-450 system. The clinical manifestations of drug induced liver injury are highly variable. Patients may present with abnormal LFTs and be otherwise asymptomatic or in severe cases, patients may present with fever, malaise, anorexia, RUQ pain and jaundice.

Drugs and toxins typically cause hepatic injury, either through direct toxic effects or through idiosyncratic reactions. The direct toxic effects are dose-dependent and have short latent periods. Some examples of direct toxins include carbon tetrachloride, acetaminophen, tetracycline, and substances found in the Amanita phalloides mushroom. Idiosyncratic reactions are not dose-dependent and have variable latent periods. Some examples of pharmacological agents that cause idiosyncratic reactions include isoniazid, chlorpromazine, halothane, and antiretroviral therapy.

Drug-induced liver disease can also be broadly categorized according to morphology: 1) cholestasis, which is caused by medications such as chlorpromazine, nitrofurantoin, erythromycin, and anabolic steroids; 2) fatty liver, which is caused by medications such as tetracycline, valproate, and anti-retrovirals; 3) hepatitis, which is caused by medications such as halothane, phenytoin, isoniazid, and alpha-methyldopa; 4) toxic or fulminant liver failure, which is caused by medications such as carbon tetrachloride and acetaminophen; and 5) granulomatous, which is caused by medications such as allopurinol and phenylbutazone.

Oral contraceptives are unusual in that they can cause abnormalities in liver function tests without evidence of necrosis or fatty change. Since this patient's liver biopsy demonstrated necrosis, oral contraceptives are not likely responsible for her hepatic dysfunction.

Acetaminophen is the most common cause of drug induced liver injury in the U.S.

Other hepatotoxic medications include:

Statins

Antibiotics - amoxicillin-clavulanate, isoniazid

Amiodarone

Antifungals

Valproic acid

The diagnosis of DILI is one of exclusion. Physicians must take a careful drug use history to rule out other potential causes of hepatotoxicity.

Patients with suspected drug induced liver toxicity should be worked up in a similar fashion to those with other forms of liver disease. Performing hepatic function tests such as AST, ALT, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and albumin are essential in the work up. Patients should also receive a hepatitis panel.

Treatment for drug induced liver injury is primarily supportive and includes early recognition of liver damage, withdrawal of the offending agent, and appropriate use of an antidote if available.

PVT

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) occurs when the portal vein (formed by the fusion of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins) becomes obstructed by a thrombus. When the portal venous system becomes obstructed, blood tends to back up into the surrounding veins, resulting in complications such as portal hypertension.

Inherited disorders that predispose patients to PVT include:

Factor V leiden mutation

Protein C and S deficiency

Antithrombin deficiency

Acquired disorders which can cause PVT include:

Cirrhosis

Sepsis

Hepatobiliary malignancy

In portal vein thrombosis, patients may present with right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting. Patients may also suffer from complications associated with portal hypertension including variceal bleeding and splenomegaly. Ascites is found infrequently, but may occur with underlying liver disease. Symptoms may differ in severity based on the extent and duration of portal vein occlusion.

Complications from liver cirrhosis can present similarly to patients presenting with PVT since both conditions cause portal hypertension. If a patient has normal LFTs, splenomegaly and varicosities WITHOUT ascites and changes in the hepatic parenchyma, PVT should be high on the differential diagnosis.

The best initial screening test for a patient with suspected portal vein thrombosis is Doppler ultrasound.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or contrast enhanced CT is used to definitively diagnose PVT.

Portal vein thrombosis may result in:

Intestinal ischemia

Septic portal vein thrombosis

Gastroesophageal varices

In patients diagnosed with PVT, treatment with anticoagulation therapy with low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH)is warranted. Once stabilized, the patient is switched to warfarin.

Hepatitis

Overview

Viral hepatitis is an infection causing inflammation of the liver, hepatocyte injury and necrosis.

There are four main RNA viruses that cause hepatitis:

Hepatitis A virus (HAV)

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)

Hepatitis D virus (HDV)

Hepatitis E virus (HEV)

HAV is an RNA picornavirus that is transmitted via the oral-fecal route, and leads to acute hepatitis. It has no chronic carrier state.

HCV is a flavivirus that is transmitted via blood and leads to acute hepatitis. The chronic carrier state (60-80% of patients) can lead to hepatocellular carcinoma.

HDV is a delta virus that is transmitted by blood, and needs HBV for co-infection or superinfection.

Mnemonic: HDV is a Defective RNA virus that requires HBV for replication.

HEV is transmitted via the fecal-oral (enteric) or waterborne routes and leads to acute hepatitis. It is more virulent during pregnancy. Remember HEV, Efor Enteric.

Hepatitis A and E are acquired via oral-fecal transmission (HAV, HEV). A useful mnemonic is: “Vowels Hit the Bowels”.

There is one DNA virus that causes hepatitis: Hepatitis B virus (HBV). It is a Hepadnavirus that is transmitted by blood. Only ~10% become chronic carriers (↑ chance if perinatal infection), which can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Acute hepatitis may present with:

Nausea

Vomiting

Malaise

Fever

Jaundice

Abdominal pain

Acute viral hepatitis has a variable incubation period. It presents with increased AST and ALT and moderately elevated GGT and alkaline phosphatase. Compare this to jaundice due to obstruction, which would have markedly elevated GGT and alkaline phosphatase and only moderately increased AST and ALT.

Chronic hepatitis may present with jaundice and hepatomegaly.

Chronic viral hepatitis is defined as:

Active disease that persists for more than 6 months without recovery OR

Asymptomatic carrier which “carries” the virus and doesn’t develop injury (due to lack of anti-surface antibody production)

Asymptomatic carriers may have slightly elevated AST and ALT and possible hepatomegaly.

Hepatitis B, C and D are transmitted via blood, can develop into chronic carriers, and can lead to cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma.

The diagnosis of hepatitis is based on serology.

The presence of antibodies against Hepatitis A indicates either an acute infection or immunity. The presence of IgM antibody, however, is specific for an acute infection.

Hepatitis B serology must be interpreted to diagnose the state of infection:

The presence of Hepatitis B surface antigen indicates either an acute or chronic infection.

The presence of Hepatitis B e antigen indicates an active and infectious virus.

The presence of anti-Hepatitis B surface antigen indicates either a prior infection or immunization.

The presence of anti-Hepatitis B core antigen IgM indicates an acute infection.

The presence of anti-Hepatitis B core antigen IgG indicates a chronic infection.

The Hepatitis B viral load can be checked by PCR as an indicator of the extent of viral activity.

HBsAg

HBeAg

Anti-HBc IgM

Anti-HBc IgG

Anti-HBs

Susceptible

-

-

-

-

-

Previous Infxn

-

-

+

+

+

Immunized

-

-

-

-

+

Acute Infxn

+

+

+

-

-

Chronic Infxn

+

+

-

+

-

The presence of antibodies against Hepatitis C and positive HCV polymerase chain reaction indicates either an acute or chronic infection.

The presence of antibodies against Hepatitis D indicates either an acute or chronic infection.

Treatment and prophylactic measures for viral hepatitis varies depending on type and severity, and may include:

Rest (as many cases are self-limited)

Interferon alpha or antivirals for Hepatitis B infection

Interferon alpha with or without ribavirin for Hepatitis C infection

Immunoglobulin given to close contacts of patients with Hepatitis A, or unvaccinated patients that have been exposed to Hepatitis B

Hepatitis A vaccine given to patients traveling to endemic areas

Hepatitis B vaccine for healthcare workers and children

Patients with chronic liver disease or impending liver failure due to hepatitis should be considered for liver transplant.

Complications of viral hepatitis include:

Chronic hepatitis

Cirrhosis

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Persistent carrier state

Fulminant hepatic failure

Death

These each depend on the type and severity of the infection.

Hep A

Hepatitis A (HAV) is one of the more common causes of acute hepatitis. Hepatitis A is caused by a non-enveloped, single-stranded picornavirus. The primary route of infection is almost always fecal-oral, which typically results in bilirubinuria, jaundice, and abdominal pain.

The U.S. has a much lower incidence of the virus compared to Mexico and Central/South America. Other risk factors for contracting the virus (in addition to foreign travel) include:

Personal contact

Consumption of shellfish

Day-care centers

Institutionalization (e.g. prisoners)

Male homosexuality

Patients initially present with a prodromal stage (i.e. fever and flu-like symptoms), often progressing to the icteric stage (i.e. bilirubinuria, pale stools, and jaundice).

The diagnostic modality of choice for hepatitis A is serologic testing, which tests for IgM antibodies to the hepatitis A virus. Anti-HAV IgG without the presence of IgM indicates prior vaccination or past infection.

Hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal pain, and jaundice are extremely common on physical exam.

Diagnosis

Liver function tests such as AST and ALT are good indicators of an HAV infection, which can exceed 10,000 mIU/mL. Bilirubin levels will also become elevated.

HAV may result in complications such as:

Prolonged or relapsing symptoms

Acute liver failure

Death (more likely in patients with concomitant Hepatitis C infection, or in the elderly)

Patients do not develop chronic liver disease as a result of hepatitis A.

The disease is usually self-limited and the treatment is generally supportive (i.e. hydration), as most patients (85%) recover completely within 6 months.

Vaccination is available for patients prior to traveling to endemic areas.

Hep D

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection is an acute and chronic inflammatory process of the liver, which requires the presence of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) to propagate, thus HDV infection always occurs in association with HBV infection.

HDV infection is transmitted percutaneously, sexually and (rarely) perinatally.

HDV infection most commonly occurs in intravenous drug users and is endemic in the Mediterranean basin.

Other risk factors include blood transfusions, high-risk sexual activity, and perinatal transmission.

Many patients are asymptomatic, but symptoms to watch for include:

Abdominal pain

Jaundice

Ascites

Nausea

Vomiting

Dark urine

The following serologic studies help confirm a hepatitis D infection:

Reverse transcriptase PCR for HDV RNA (most sensitive)

anti-HDV IgM (initially) and anti-HDV IgG

anti-HBc IgM

HBsAg (may be suppressed or undetectable during active HDV replication)

Additional laboratory findings may include elevated AST and ALT (above 500 IU/L), INR greater than 1.5, or elevated prothrombin time.

Complications of HDV may include:

Severe hepatitis

Chronic carrier state

Cirrhosis

Encephalopathy

Fulminant liver failure

One of the most feared complications of HDV is a superinfection, which occurs when a patient becomes infected with the hepatits D virus who is already positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen(ie chronic carrier or acute HBV infection). These patients can progress to fulminant liver failure very rapidly.

Treatment is primarily supportive in HDV infection. The patient's liver enzymes and mental status should be observed very carefully. In the case of chronic infection, treatment with interferon alfa may be considered.

Increasing liver enzymes and decreased mental status may be signs of fulminant liver failure, which requires liver transplantation.

Administration of the Hepatitis B vaccine is protective against Hepatitis D.

Hep E

Hepatitis E (HEV) is a single-stranded RNA virus that is transmitted via contaminated water and the fecal-oral route. The resulting liver infection is usually self-limited.

HEV is endemic in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

It most commonly occurs in fecally contaminated water sources within endemic areas and with ingestion of undercooked pork.

Patients typically present with 2 phases of symptoms, the prodromal phase and the icteric phase.

Prodromal symptoms include:

Myalgias

Mild fever

Right upper quadrant pain

Nausea/vomiting

Weight loss

Anorexia

Icteric phase symptoms include:

Light colored stools

Jaundice

Pruritis

The best tests in diagnosing HEV infection are serum HEV RNA and anti-HEV immunoglobulin (IgM).

Other helpful laboratory tests include:

ALT

AST

Bilirubin

Alkaline phosphatase

Elevated (10-20 times normal) aminotransferases are the hallmark in acute viral hepatitis.

HEV may result in complications such as encephalopathy, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and fulminant hepatic failure.

For unknown reasons, pregnant woman in their third trimester have an increased risk of developing fulminant hepatic failure following Hepatitis E infection.

Treatment of HEV infection is primarily supportive. Liver transplant is required in patients with fulminant hepatic failure.

Preventive measures include careful cooking of food and drinking clean water.

Hep B

Hepatitis B is a double-stranded DNA virus, which causes acute and chronic inflammation to the liver.

The virus is most commonly transmitted via bodily fluids such as blood, semen and vaginal secretions.

HBV infection most commonly occurs in:

Accidental needle sticks

Sharing needles

Sexual contact

Perinatal transmission

Common symptoms during the acute phase include:

Scleral icterus

Abdominal pain

Pruritus

Myalgias

Possible progression to fulminant hepatic failure

Patients with chronic disease may be asymptomatic or complain of:

Myalgias

Nausea

Abdominal discomfort

Mild jaundice

Diagnosis of hepatitis B is based on serological studies. The following serum markers are positive during acute hepatitis B infection:

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

Anti-HBV core antibody IgM (anti-HBc)

HBeAg (marker of infectivity)

As long as HBeAg is in the serum, patients can still infect others.

The following table summarizes the descriptions of the hepatitis B serology markers:

HBsAg

Surface antigen, indicates active infection or carrier state (HBsAg: virus is preSent)

HBsAb

Antibody against HBsAg, presence indicates immunity to HBV

HBcAg

Core antigen

HBcAb

Antibody against core antigen. Critical for diagnosis during the window phase, when HBsAg is absent but HBsAb isn't detectable yet. Doesn't confer immunity.

HBeAg

Core antigen. Presence indicates transmissibility (HBeAg=rEplication)

HBeAb

Antibody against HBeAg, indicates low transmissibility

In general, chronic hepatitis B infection is characterized by positive HBsAg and anti-HBc IgG antibody. Presence of HBsAg for longer than 6 months alone is indicative of chronic infection.

Inactive carriers of the HBV are negative for HBeAg, but positive for HBsAg.

Prior HBV infection is characterized by anti-HBs (IgG) and anti-HBc (IgG).

Patients immunized will only be positive for anti-HBs antibodies.

Liver biopsy is not always required, but helps determine the extent of damage to the liver.

Hepatitis B viral infection may result in:

Cirrhosis

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Renal failure

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Fulminant hepatic failure

In unvaccinated patients, immediate treatment involves administration of the Hepatitis B vaccine and Hepatitis B immune globulin following exposure to HBV.

Pharmacologic therapy is recommended for patients with chronic active hepatitis B (positive HBV DNA, elevated liver enzymes, and positive HBeAg), acute hepatic failure, and cirrhotic patients. First-line agents include: pegylated interferon alpha (PEG-IFN-a),entecavir, andtenofovir. Other agents such as lamivudine (3TC), telbivudine, and adefovir are second- or third-line agents.

Routine vaccination is routinely given to healthcare workers and children.

Hep C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a single-stranded RNA flavivirus.

HCV is transmitted via blood, and possibly sexual contact. Risk factors include:

Intravenous drug users

Accidental needle stick

Sexual intercourse with an infected individual

Blood transfusions

Perinatal transmission

Infection can result in both acute and chronic inflammation of the liver. The acute process is typically self-limited, while a chronic HCV infection is more progressive in nature, which can lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and even liver failure.

The best initial diagnostic test is a HCV antibody test (anti-HCV), which looks for antibodies against the virus within the patient’s serum.

The best test for confirmation of infection is qualitative PCR, which detects whether the virus is in the patient’s blood.

Other tests include quantitative HCV testing (detects amount of virus within blood) and genotype testing. This helps determine both the type and length of treatment, as some genotypes are more susceptible to certain medications.

Most patients with chronic HCV infection are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Symptomatic patients may present with:

Fatigue/malaise

Myalgias

Jaundice

Nausea

Vomiting

Weight loss

Other conditions that are associated with Hepatitis C infection include:

Mixed cryoglobulinemia

Lymphoma

Thyroiditis

Polyarteritis nodosa(more commonly associated with Hepatitis B)

Membranous nephropathy

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

Porphyria cutanea tarda

Lichen planus

In patients with HCV, mixed cryoglobulinemia is diagnosed by:

Palpable purpuraor other skin manifestations

Biopsy can confirm diagnosis

Low complement levels

Circulating serum cryoglobulins

Patients with mixed cryoglobulinemia may also have elevated rheumatoid factor titers.

Patients with either mixed cryoglobulinemia or porphyria cutanea tarda should be screened for HCV.

Complications of HCV infection may include:

Chronic hepatitis (80% of patients)

Cirrhosis(in 50% of those with chronic disease)

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Persistent carrier state

Liver failure

Death

The current standard of care for treatment of patients with HCV is pegylated interferon and ribavirin.

The newest 2014 recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Disease Society of America include the addition of a polymerase inhibitor(sofosbuvir) to the PEG-IFN/RBV combination in the treatment of chronic HCV.

Sofosbuvir is also now available in combination with ledipasvir(combination trade name Harvoni) for treatment of disease caused by genotype 1. It does not require coadministration with interferon or ribavirin.

Once diagnosed, patients should wait at least 12 weeks before starting therapy to allow spontaneous clearance.

Quantitative HCV tests (i.e. viral load) are carried out to assess response to treatment. The timing of these are dependent on the serotype of virus, and may involve testing after 4 weeks of treatment, 12 weeks of treatment, and/or at the cessation of treatment.

If patients do not eradicate the virus, it is recommended not to retreat them. These patients will be monitored for progressive fibrosis and evaluated for liver transplantation.

All patients with chronic hepatitis C should receive vaccination against Hepatitis A and B if not already immune.

Colon

IBS

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a benign idiopathic disorder characterized by abnormal activity of the GI tract while at rest.

Other associated findings include depression and anxiety.

Physiologic symptoms include a combination of:

Diarrhea

Constipation

Abdominal pain

Abdominal bloating

IBS symptoms are notably relieved by defecation.

IBS may be classified as:

C onstipation-predominant

D iarrhea-predominant

A lternating

P ost-infectious

Certain red-flag symptoms should prompt workup for a more serious condition. These include:

Anemia

Bleeding

Weight loss

Early satiety

The Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome are used for diagnosis. They specify that the patient must have:

Recurrent abdominal pain for at least 1 day per week in the last 3 months PLUS two or more of the following:

Related to defecation

Associated with a change in stool frequency

Associated with a change in stool form (appearance)

Irritable bowel syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion. Other etiologies should be ruled out first with lab studies and stool exams, and clinical suspicion for IBS is needed.

Differential diagnosis includes:

Inflammatory bowel disease

Celiac disease

Depression

Somatization

GI malignancy

Obstruction

Malabsorption

Infectious etiologies

Treatment is usually based upon dietary and lifestyle modifications for symptoms relief. These may include:

Lactose free diet

Exclusion of gas producing foods

Judicious water intake (for predominant constipation)

Fiber supplementation

Avoidance of caffeine to limit anxiety and symptom exacerbation

Anti-spasmodic or anti-cholinergic drugs may be used as adjunctive treatment. The best treatment remains stress management.

When medications are indicated, treatment options include:

Diarrhea-predominant

Antidiarrheals (e.g. loperamide, diphenoxylate hydrochloride+atropine sulfate)

Serotonin receptor antagonists (e.g. alosetron)

Antibiotics (e.g.rifaximin) for severe IBS without constipation that is refractory to other treatments

Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. imipramine, amitriptyline)

Antispasmodic agents (e.g. dicyclomine hydrochloride, hyoscyamine sulfate)

Constipation-predominant

Laxatives(e.g. lubiprostone, linaclotide, methylcellulose)

Chloride channel activators

Guanylate cyclase C agonists

Celiac Sprue

Celiac sprue (i.e. gluten intolerance) is an immune-mediated destruction of the mucosa of the small bowel.

Pathogenesis involves the ingestion and biochemical breakdown of gluten (found in wheat, barley, rye), and the subsequent autoimmune inflammatory reaction to gliadin, an alcohol-soluble fraction of gluten. This inflammatory reaction damages the gut mucosa, causing malabsorption.

Celiac sprue has a strong hereditary component--HLA haplotypes DQ2 and DQ8 are strongly linked to disease. These HLA molecules present gliadin to helper T cells, which mediate inflammatory damage.

Other than disease in a first-degree relative, risk factors for celiac sprue include:

Presence of another auto-immune condition (e.g., type 1 diabetes mellitus, thyroid and liver disease)

Down syndrome

Characteristically, celiac disease manifests during infancy and before school age. In the classic form of childhood celiac disease, symptoms and signs of malabsorption become obvious within some months of starting a gluten-containing diet.

Children may present withfailure to thrive, and proximal muscle wastingmay be seen. In up to one quarter of children diagnosed, Rickets may be a presenting symptom.

Gastrointestinal symptoms of celiac sprue include:

Foul-smelling diarrhea

Abdominal pain

Weight loss

Bloating

Fatigue

Steatorrhea

Extraintestinal manifestations of celiac sprue include:

Anemia

Neurologic symptoms (motor weakness, paresthesias)

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Hormonal disorders (amenorrhea/infertility in women, impotence/infertility in men)

For suspected celiac disease, the best initial test is a serum level of immunoglobulin A anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody (IgA TTG). Other antibodies that can be tested include anti-endomysial and anti-gliadin. When IgA deficiency is suspected, or in children less than 2 years old, IgG anti-gliadin may also be drawn.

Other useful lab tests include:

Electrolytes (may be low, evidence of malabsorption)

Hematologic tests (anemia, low serum iron, prolonged prothrombin time)

Stool examination (fat malabsorption)

Blood cholesterol (may be low)

Vitamin D and B12 (may be low)

The gold standard in diagnosing celiac sprue is a duodenal biopsy, which shows:

Atrophic or absent villi

Hypertrophic crypts

Increased lymphocytes

Radiographic studies may be useful in untreated celiac sprue. Barium studies may show small bowel dilatation.

The primary treatment of celiac sprue is the avoidance of gluten-containing products, such as wheat, barley and rye.

Iron, folate or vitamin supplementation may be necessary until the patient is able to absorb these nutrients on his or her own.

Dermatitis herpetiformis, if present, can be treated with a gluten-free diet anddapsone.

In patients with disease refractory to treatment, corticosteroids may be helpful.

Celiac sprue may result in the following long term complications:

Anemia

Osteopenia/osteoporosis

Bleeding diathesis(increased tendency to bleed, secondary to malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamin K)

Weight loss

Severe dehydration

Malnutrition

Tropical sprue is an acquired chronic diarrheal disease similar to celiac sprue, affecting patients living in tropical areas. It may present years after the patient has left the tropical area, and is thought to be infectious or toxic in origin.

Patients present with:

Diarrhea

Steatorrhea

Weight loss

Fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies

Diagnosis relies on a combination of:

Serum findings,which may show a low-level of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), B12, folate, and lack of anti-endomysial, anti-gliadin, and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies

Stool studies,showing excess fecal fat

Histologic findings on endoscopy,revealing flattening of villi and inflammation in the small bowel

It is important to rule out GI infections, autoimmune diseases, and celiac sprue prior to assigning a diagnosis of tropical sprue.

Treatment of tropical sprue consists of tetracycline plus folic acid for 3-6 months.

Unlike celiac sprue, patients with tropical sprue have no response to the removal of gluten from the diet.

Infection

Whipple

Whipple’s disease is asystemic infection caused by _Tropheryma whippelii_that typically affects the gastrointestinal tract, but may involve the heart, bones, lungs, and central nervous system.

Tropheryma whippelii (T. whippelii) is a gram-positive, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive bacillus bacterium that causes Whipple's disease.

The risks associated with T. whippelii are unknown, but the bacterium is more common in sewage and wastewater.

Patients typically present with:

Weight loss

Arthralgias

Diarrhea with/without bleeding

Abdominal pain

The classical triad of symptoms is:

Arthralgia

Diarrhea

Lymphadenopathy

Oculomasticatory myorhythmia is pathognomonic for Whipple's disease. It involves eye movement disturbances along with rapidly repetitive movement of facial muscles.

Other symptoms include:

Fever

Cognitive dysfunction

Endocarditis

The best initial diagnostic test for T. whippelli infections is quantitative PCR of the stool and saliva, which helps detect bacterial load.

The diagnostic modality of choice is endoscopy with small intestine biopsy, which classically reveals PAS-positive macrophages and villous atrophy.

T. whippelii may result in complications such as:

Endocarditis

Malabsorption

Dementia

Skin hyperpigmentation

Arthritis

Steatorrhea

Nystagmus

The mainstay of treatment is antibiotic therapy for 1-year. The treatment of choice is IV ceftriaxone for 2-weeks, followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) for 1-year.

Noncompliance with the full antibiotic course leads to high recurrence rates, and mortality if the disease is left completely untreated.

T Canis

Toxocariasis (also known as visceral larva migrans) is infection acquired from the ingestion of eggs secreted by the roundworm Toxocara canis that inhabits the small intestine of dogs.

Adult Toxacara reside within the small intestine of dogs and excrete the eggs with their stool. Once the eggs are ingested, they hatch and the larvae are able to penetrate the intestinal wallwhere they travel through the circulation and infect other portions of the body.

Most commonly occurs in young children who come into contact with dog feces at the playground or sandbox. Other risk factors include being a veterinarian and having poor hygiene.

There are 2 major syndromes associated with Toxocara canis: visceral larva migrans(VLM) and ocular larva migrans (OLM). Symptomatic presentation can vary depending on which organs the larvae come into contact with.

VLM is characterized by:

Fever

Anorexia

Hepatomegaly

Hepatitis

Pneumonitis

Urticaria

OLM is characterized by:

Unilateral decreased vision

Seeing floaters

Strabismus

Uveitis

The diagnosis of toxocariasis requires a high degree of suspicion and is dependent on serum laboratory test results. CBC may show eosinophilia. There may also be elevated IgE, and a positive ELISA antibody assay (detects antibodies against secretory antigens).

CT and ultrasound are helpful in diagnosing liver, pulmonary, and CNS lesions.

It is important to perform a fundoscopic examinationon all patients suspected of toxocariasis. Patients may present with retinal exudates, retinal detachment, and peripapillary inflammation.

Toxocara canis may result in:

Vision loss

Myocarditis

Respiratory failure

Encephalitis

Seizures

The treatment of choice in VLM and OLM is albendazole. When there is severe pulmonary, cardiac, or CNS involvement, prednisone is warranted.

Enterobius

_Enterobius vermicularis_is a pinworm and is the most common helminth in US, primarily infecting children under age 12.

_Enterobius vermicularis _is transmitted via the fecal-oral route.

The typical clinical presentation is a child under 12 with intense anal pruritis that worsens at night.

The Scotch tape test is used to recover eggs from perianal skin. It is effective due to the migration of female helminths out of the anus at night, and the deposition of eggs on the perianal skin. Eggs are NOT found in stools (vs other nematodes).

Treatment for an Enterobius vermicularis _infection is an antihelminthic for both the affected patient and all household contacts and caretakers. Mebendazole, pyrantel pamoate, and albendazole are all active against _E. vermicularis.

For successful eradication, individuals should receive three doses, three weeks apart. Reinfection is common.

Of note, all above mentioned drugs are category C for pregnant patients, and the CDC has limited data on their use during pregnancy. If medically necessary, treatment should be withheld until the 3rd trimester.

Cystoisospora

Infection with _Cystoisospora _involvesingestion of oocysts from food or water contaminated with human or animal feces of an affected host.

Diagnosis is achieved through visualization of oocysts in the feces.

Treatment of choice is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Ciprofloxacin is first line for patients with sulfa allergies.

Typical clinical presentation of a Cystoisospora infection involves an immunocompromised host with a CD4 count < 50 who has been experiencing secretory diarrhea with possible significant weight loss and wasting. It is found more commonly in tropical and subtropical regions.

Microsporidia

Microsporidia are a group of unicellular fungi (once thought to be protists)that cause microsporidiosis, a form of chronic diarrhea and wasting, in immunocompromised hosts.

Enterocytozoon species are the most well-known human pathogens among the microsporidia.

Clinical presentation involves an immunocompromised host with a CD4 < 100 presenting with watery diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain.

Diagnosis is achieved through visualization of spores in stool samples and/or with a modified trichome stain.

Treatment is with fumagillin or albendazole.

In addition to microsporidia such as Entercytozoon species, other pathogens to consider in the patient with severe watery diarrhea include:

Gram-positive bacteria (Staph aureus, Clostridium)

Gram-negative bacteria (Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella, Campylobacter)

Viruses (rotavirus)

Parasites (cryptosporidium)

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium parvum (C. parvum) is an intracellular protozoan parasite that is predominantly associated with diarrhea and biliary disease after the organism’s infectious oocysts have been ingested.

The Cryptosporidum oocysts areimmediately infectiousafter excretion. Once ingested, the oocysts undergo encystation and release sporozoites within the small bowel that attach to the epithelial cells and interfere with intestinal absorption and secretion.

Transmission most commonly occurs via the fecal-oral route from contaminated sources such as food and water.

High-risk populations include:

Immunodeficiency (e.g. AIDS)

Day-care centers

Backpackers who consume unfiltered water

People who handle infected animals

Immunocompetent infected hosts are usually asymptomatic, but may also present with:

Abdominal cramping

Watery diarrhea

Low-grade fever

Malaise

Nausea

Immunocompromised hosts (e.g. AIDS, immunodeficiencies) tend to present with a more chronic, severe gastrointestinal illness. These patients commonly present with:

Diffuse, foul-smelling diarrhea

Weight loss

Biliary disease(e.g. acalculous cholecystitis, sclerosing cholangitis)

The best, most cost effective initial diagnostic test is microscopic identification of the oocysts within the stool. This can be very difficult and may require multiple samples.

The most accurate diagnostic test for Cryptosporidium is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Cryptosporidium may result in complications such as:

Severe dehydration

Malabsorption

Weight loss

Acalculous cholecystitis

Cholangitis

Pancreatitis

Immunocompetent hosts respond well to fluid resuscitation and typically do not require pharmacological treatment. When therapy is required, the drug of choice in both children and adults is nitazoxanide.

The most important therapy for HIV-infected patients is supportive(e.g. fluid and electrolyte replacement) and initiation of HAART if not already begun. If this fails, nitazoxanide should be initiated.

Biliary Disorder

Primary Biliary Cholangitis

Primary biliary cholangitis (formerly primary biliary cirrhosis) (PBC) is an autoimmune disorder in which there is continuous destruction of the intrahepatic bile ducts, resulting in cholestasis and end stage liver disease.

PBC most commonly occurs in middle-aged females, and tends to have a greater prevalence in people of Northern European descent.

Pruritus and fatigue are the 2 most common presenting symptoms. Other symptoms include:

Vague musculoskeletal pain

Skin hyperpigmentation

Right upper quadrant tenderness

Xanthomas and xanthelasmas

A diagnosis of PBC is confirmed when two of the following three criteria are met:

Positive anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA) within the serum

Elevated alkaline phosphatase

Liver biopsy revealing destruction of the intrahepatic bile ducts

Other helpful diagnostic tests in diagnosing PBC include ultrasound, CT, and MRI.

Complications of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) include:

Malabsorption

Cirrhosis

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Metabolic bone disease (e.g. osteopenia, osteoporosis)

Note that metabolic bone disease in patients with PBC may be due to the inhibition of osteoblast activity by a retained toxin rather than vitamin D malabsorption.

The only approved pharmacologic agent in the treatment of PBC is ursodeoxycholic acid. This drug improves liver function test abnormalities and may delay the progression of disease symptoms.

Other second line agents include corticosteroids, methotrexate, and colchicine. Antipruritic agents include antihistamines (first-line), cholestyramine and colestipol.

Liver transplantation is the only curative therapy for PBC.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a progressive disorder characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ducts, which results in cholestasis and cirrhosis of the liver.

The exact etiology of PSC is still unknown, but there are several factors shown to have an increased risk, such as:

Ulcerative colitis

Male gender (70%)

Positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies(possibly predominantly classical p-ANCA or atypical p-ANCA, but is debated in literature, and are of limited diagnostic value)

First-degree relatives with the disease

Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis typically present with:

Fatigue

Pruritus

Jaundice

Right upper quadrant pain