03 Gyn

Benign Ovarian Tumor

follicular cysts

corpus luteum cysts

cystadnenomas

endometrioma

benign teratomas

stromal cell tumors

Follicular

Follicular cysts arise from ovarian follicles in which fluid accumulates in a Graafian (mature) or previously ruptured follicle. They are composed of granulosa cells, are cystic (3 cm in diameter), occur in the first 2 weeks of the menstrual cycle and may regress over the menstrual period. This is the most common ovarian mass in a reproductive-age woman.

The clinical presentation of follicular cysts includes:

Abdominal pain and fullness

Palpable tender mass on bimanual exam

Peritoneal signs if torsion or rupture occur, which can cause sterile peritonitis

Patients typically require no treatment besides a follow-up ultrasound to ensure cyst resolution. If the mass does not regress, or if there is a high suspicion of cancer, an ovarian cystectomy can be performed. Note: do not aspirate these cysts.

Corpus Luteum Cysts

Corpus luteum cysts occur when fluid accumulates in corpus luteum. They are composed of theca cells, are cystic or hemorrhagic, usually larger and firmer than follicular cysts, and are more common in later weeks of the cycle, and in early pregnancy.

The clinical presentation of corpus luteum cysts includes:

Abdominal pain

Palpable tender mass on bimanual exam

Greater risk of torsion or rupture than follicular cysts

Like with follicular cysts, patients typically do not require treatment. If the mass does not regress, or if there is a high suspicion of cancer, an ovarian cystectomy can be performed. A rupture with significant hemorrhage requires surgical hemostasis with cystectomy.

Cystadenomas

Mucinous or serous cystadenomas are the most common ovarian tumors. Originating in epithelial tissue, they may resemble endometrial or tubal histology, contain cystic or mucinous contents, and may form calcifications (psammoma bodies), which may become extremely large.

These tumors are frequently asymptomatic until they become significantly large, at which point they will present as a palpable mass on bimanual exam.

Treatment of mucinous and serous cystadenomas includes unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or total abdominal hysterectomy-bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy if postmenopausal.

Endometrioma

An ovarian endometrioma is a mass consisting of endometrial tissue and the blood which results from the cyclic shedding of that tissue. Ovarian endometriomas result from the growth of ectopic endometrial tissue on the ovary, and their behavior is similar to that of other sites of endometriosis.

These masses are frequently asymptomatic, but when symptomatic may present as a tender palpable mass and have similar symptoms to endometriosis, including:

Abdominal pain

Dyspareunia

Potential infertility

Because of high recurrence rates, cystectomy or oophorectomy is often required. Pharmacologic agents that can be used to lessen symptoms include:

Oral contraceptives and progestins

GnRH agonists

Danazol

Benign Teratomas

Benign cystic teratomas (i.e. dermoid cyst) originate from germ cells and are composed of multiple dermal tissue layers (such as hair, teeth, and sebaceous gland).

These masses are often asymptomatic, but if they rupture the oily contents that are released can cause peritonitis.

Treatment of dermoid cysts involves cystectomy with attempted preservation of the ovary if benign.

Stromal Cell Tumors

Stromal cell tumors originate from granulosa theca (estrogens), or Sertoli-Leydig cells (testosterone and other androgens) and secrete hormones based on the cells of origin. They have malignant potential.

Clinical findings associated with stromal cell tumors include:

Precocious puberty with granulosa theca cell tumors

Virilization with Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors

Treatment of stromal cell tumors is similar to mucinous or serous cystadenomas and consists of unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for premenopausal women, or total abdominal hysterectomy-bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy if postmenopausal.

Diagnosis

Testing for tumor markers may be helpful in differentiating malignant masses from benign masses, however it is worth remembering that CA-125 and other tumor markers may be elevated in several benign conditions, as well. For more information on tumor markers in ovarian cancer, see our topic on malignant ovarian tumors. A definitive diagnosis requires pathologic examination, such as a frozen section.

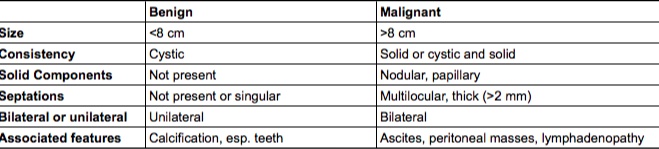

Ultrasound can be used to evaluate the mass. Findings associated with benign ovarian masses include:

Size < 8cm

Cystic consistency

No solid components

No septations or singular septations

Unilateral mass

Associated with calcification

Complications

Complications associated with benign ovarian tumors include ovarian torsion, and tumor rupture with hemorrhage.

Meigs

Triad of benign ovarian tumor (usually ovarian fibroma), ascites, and pleural effusion.,

Malignant Ovarian Tumor

Ovarian cancer typically originates from either epithelial cells (90% of cases) or germ cells. Serous cystadenocarcinoma is the most common malignant ovarian tumor.

Risk factors for developing ovarian cancer include:

Genetic causes: Family history, BRCA-1 or BRCA-2, Lynch syndrome (HNPCC)

Increased total duration of ovulation: Infertility, nulliparity, early menarche, late menopause. Ovarian masses are more likely to be malignant in postmenopausal women.

Risk can be decreased by oral contraceptives or pregnancy, as this shortens the total time ovaries spend developing mature follicles.

Symptoms and PE

Malignant ovarian tumors are usually asymptomatic, or have minimal symptoms until it is late in the course of the disease.

Initial symptoms of ovarian cancer include:

Bloating

Early satiety

Dyspepsia

Abdominal pain

Pelvic pain

Late symptoms of ovarian cancer include:

Back pain

Urinary frequency/urgency

Constipation

Fatigue

Dyspareunia

Menstrual changes

Physical exam findings of malignant tumors include fixed, solid, irregular, and bilateral adnexal masses.

Markers

Tumor markers associated with ovarian cancer include elevated:

CA-125

LDH

AFP

CEA

It is important to remember that the tumor markers associated with ovarian cancer are neither sensitive nor specific. They serve three purposes:

To risk-stratify patients with an ovarian mass (especially in postmenopausal patients) while remembering that not all patients with elevated tumor markers have a malignancy, and not all patients with normal tumor markers are cancer-free.

To monitor response to treatment

To monitor for recurrence

CA-125 is elevated in many gynecologic pathologies including

endometriosis

ovarian epithelial tumors

endometrial cancer, and

fallopian tube cancers.

It is also elevated in many non-gynecologic processes in the abdomen such as gastrointestinal cancers, diabetes, and liver cirrhosis.

Elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is seen in yolk sac tumors.

CEA should be ordered to rule out gastrointestinal cancer with metastasis to the ovary (Krukenberg tumor).

LDH is elevated in ovarian dysgerminomas (the female analog of the testicular seminoma in males).

Diagnosis

Ultrasound can be used to detect malignant ovarian tumors. Findings associated with a malignant mass include:

Size > 8 cm

Solid, or cystic and solid consistency

Nodular or papillary solid components

Multilocular, thick (>2 mm) septations

Bilateral tumors

Associated features including ascites, peritoneal masses, lymphadenopathy

Treatment

Treatment for malignant epithelial ovarian cancer is based on surgery plus chemotherapy and radiation as needed.

Surgical removal is a total abdominal hysterectomy plus bilateral salpingo-oophrectomy (TAH/BSO).

Multiagent chemotherapy is typically used for malignant ovarian germ cell tumors.

Another treatment for malignant ovarian germ cell tumors is a unilateral salpingo-oophrectomy (because they are rarely bilateral) if fertility is desired and TAHBSO is refused.

Complications

Pseudomyxoma peritonei is a complication of ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma in which rupture of the tumor produces copious mucinous ascites and peritoneal mucinous tumors.

Ovarian cancer has a poor 5-year survival rates because tumors are frequently in advanced stages when they are detected.

Breast Cancer Overview

Breast cancer refers to malignant neoplasms of the breast that can arise from ductal or lobular tissue. Ductal carcinomas account for 80% of cases and are more aggressive, whereas lobular carcinomas account for 20% and are less aggressive, but more difficult to detect.

Remember that a breast mass in women over the age of 50 is carcinoma until proven otherwise.

In decreasing frequency, mets occur in lungs > bone >> liver, brain, ovaries.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in the US and is responsible for the second highest number of cancer deaths.

Axillary node involvement is the most important prognostic factor in breast cancer.

It occurs most often in the upper outer quadrant of the breast, which metastasize to the axillary nodes.

Risks

Genetic risk factors associated with breast cancer include:

Family history (first-degree relative)

BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations

Ovarian, endometrial, or prior breast cancer (hints of possible inherited cancer syndromes such as BRCA)

Early menarche or late menopause (increased estrogen exposure)

Non-genetic risk factors associated with breast cancer include:

Lifestyle factors (e.g. obesity, alcohol)

Toxic exposures (e.g. diethylstilbestrol, industrial chemicals or pesticides, radiation exposure)

Nulliparity or late first pregnancy (35 years of age or older)

Hormone replacement therapy due to exogenous estrogen

Symptoms

The clinical presentation of breast cancer can vary as it advances, but it can be:

Asymptomatic and undetected

A painless breast lump with possible nipple discharge

A palpable solid and immobile lump

Peau d’orange appearance (which is skin thickening that makes the breast look like an orange peel due to lymphatic obstruction) with possible nipple retraction

Axillary lymphadenopathy

Treatment

Neoadjuvant therapy, such as chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and radiation therapy should be used for local lesions that extend beyond the breast.

If neoadjuvant therapy has reduced the tumor size, surgical resection and radiation therapy can be performed.

Metastases can be treated with systemic therapy, but surgical resection and radiation can be used for solitary lesions.

In inflammatory breast cancer, mastectomy, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy should all be utilized.

Complications

Complications associated with untreated breast cancer include metastases to bone, thoracic cavity, brain, and liver.

Complications of surgical treatment include:

Lymphedema following node dissection, creating cosmetic disfigurement, impaired wound healing, decreased range of motion, and increased risk of infection.

Winged scapula following injury to the long thoracic nerve

Treatment of the various types of breast cancer can be found in the topic, Breast Cancer Specific Types (Breast Cancer: Specific Types).

Intraductal Papillomas

Intraductal papillomas are benign lesions of breast ductal tissue that may have malignant potential.

The classic finding in intraductal papilloma is bloody nipple discharge, though it is worth remembering that the discharge may also be non-bloody. Other associated findings include breast pain and a palpable mass behind the areola.

A biopsy should be performed in order to rule out breast cancer. In the case of intraductal papilloma, ductal lavage by microcatheter is the preferred way to test for abnormal intraductal cells because it is more accurate than examining nipple fluid aspirate.

Treatment of intraductal papillomas is surgical removal.

Breast Cancer Wkup

The approach to the patient with suspected breast cancer (with or without a palpable mass) begins with a mammogram. Most are detected through an abnormal screening mammogram, but 20% of breast cancers are not detected with mammography.

Ultrasound is the first line imaging technique for patients under 30 or who are pregnant.

If there is no palpable mass and the mammogram is normal, repeat every 1-2 years.

If there is no palpable mass, but the mammogram is abnormal:

If there is low suspicion of malignancy, repeat mammography in 6 months.

If there is high suspicion, biopsy

A palpable mass with low suspicion (following mammography) showing an asymptomatic simple cyst on ultrasound should have repeated mammography in 6 months.

A palpable mass should be biopsied if ultrasound findings show a solid mass or symptomatic complex cyst, or if mammography shows a high suspicion of malignancy.

If aspiration of a breast cyst yields non-bloody and non-purulent fluid, and the cyst resolves completely with aspiration, the patient should return if the cyst recurs or if new symptoms develop. Note: Some sources recommend a follow-up visit at 4-6 weeks to ensure that the cyst does not recur. Other sources argue that such follow-up is unnecessary in patients with non-bloody, non-purulent aspirate, and that the patient should return only if symptoms recur.

If aspiration of a breast cyst yields purulent fluid, it should be sent for culture. Bloody aspirate should be sent for cytology.

If the biopsy results (fine needle aspiration) show bloody aspirate or residual mass after aspiration, a more definitive biopsy (core or open) is necessary.

If the biopsy results show malignant findings, stage and then begin treatment for breast cancer. Treatment for specific types of breast cancer is covered in the topic Breast Cancer: Specific Types.

Fine needle aspiration is quick, has high sensitivity and specificity, but cannot differentiate carcinoma in situ from invasive carcinoma. In these cases a core biopsy, which preserves the original arrangement of the cells as well as the cells themselves, provides a better diagnosis and offers histological diagnosis.

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is typically squamous cell carcinoma (80% of cases), but can be adenocarcinoma (15% of cases) or a mixed adenosquamous (5% of cases).

Risks

Risk factors for cervical cancer include:

Early sexual intercourse

HPV 16, 18, 31, 33

Multiple partners

Smoking

Immunodeficiency

History of STDs

The incidence of Invasive Cervical Carcinoma has been reduced dramatically due to the success of the pap smear, with an incidence of approximately 12,000 cases/year. In order of incidence: endometrial > ovarian > cervical > vulvar > vaginal.

Cervical Dysplasia

Cervical dysplasia is a pre-cancerous squamous cell lesion of the cervix that may progress to invasive cervical cancer in up to 22% of cases, depending on the grade.

It is usually detected by pap smear that will show koilocytes, which are cells with clear halo surrounding hyperchromatic, atypical nuclei that begin at the basal layer and extend outward.

Dysplasia may progress to carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma, or it may regress spontaneously.

Although typically asymptomatic in early stages, cervical cancer can present with the following symptoms:

Vaginal bleeding (postcoital or spontaneous)

Pelvic pain

Cervical discharge

A palpable cervical mass

Cervical dysplasia is detected by pap smear and diagnosed by biopsies (colposcopy, or cold-knife cone). Pap smear and colposcopy can discover cervical dysplasia before it progresses to invasive carcinoma. However, cancer can arise rapidly, so a recent normal pap smear does not rule out cervical cancer!

CIN 1 with koilocytic atypia:

Other diagnostic studies include punch biopsy of visible lesion, and a cone biopsy (“cold-knife cone”) to determine the extent of invasion.

Imaging that can be useful in determining the extent of disease includes CT, MRI, and ultrasound.

Cancer Spread

Cervical cancer spreads by local extension, and the 5-year survival rate based on extent of invasion is as follows:

Over 90% for microscopic lesions

65-85% for visible lesions with growth beyond the cervix but limited to the uterus

40% for those lesions that extend beyond the uterus

20% for metastatic lesions

Renal failure is the most common cause of death in patients with invasive cervical cancer.

Invasion of bladder and ureters causes ureteral obstruction which leads to hydronephrosis and postrenal failure.

Treatment

Surgery is the first-line treatment for invasive cervical carcinoma, with chemotherapy and radiation required in certain cases. Chemotherapy is used to prevent distant recurrence, while radiation reduces local recurrence. Treatment is determined by stage, as outlined below.

For small invasive lesions with close surgical margins, chemotherapy should be used postoperatively to prevent distant recurrence from micrometastasis not detected at the time of surgery.

Stage IA disease: Surgical management, without chemotherapy or radiation. (Internal radiation therapy may be used in patients who cannot safely undergo surgery.)

Stage IB and IIA-B, III, and IVA: various combinations of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

Stage IVB: Palliative treatment (radiation and/or chemotherapy). Hysterectomy is not indicated.

Recurrent cancer is treated with pelvic exenteration, which is a surgical procedure that removes all pelvic organs (uterus, tubes, ovaries, bladder, distal ureters, rectum, sigmoid colon, pelvic floor muscles, ligaments).

The Gardasil vaccine (tetravalent against HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18) is now FDA approved for both males and females. Note: women who have received the Gardasil vaccine still need regular pap smears!

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer is an adenocarcinoma of uterine tissue that is commonly related to exposure to high levels of estrogen. It is the most common of the gynecologic cancers. (Note: According to the CDC, the 4 gynecologic cancers are: endometrial, ovarian, cervical, and vulvar. Breast cancer is NOT classified as a gynecologic cancer.)

According to the endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia schema, which has largely replaced the simple/complex hyperplasia with/without atypia classification, the following three diagnostic categories are:

Benign endometrial hyperplasia (benign)

Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia ( precancerous)

Endometrial adenocarcinoma, endometrioid type, well differentiated (malignant)

Risks

Risk factors include:

Prolonged unopposed estrogen exposure

HNPCC (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer)

Diabetes and obesity

Hypertension

Polycystic ovarian syndrome and chronic anovulation

Nulliparity

The average age of diagnosis is 61, but the age range of 50-59 is the largest affected group.

Symptoms

Endometrial cancer manifests clinically with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Note that the most common cause of vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women is atrophic vaginitis, but endometrial cancer must be ruled out.

In addition to postmenopausal vaginal bleeding, symptoms associated with endometrial cancer include:

Heavy menses

Mid-cycle bleeding

Abdominal pain

Fixed ovaries or uterus if tumor has extended locally

Diagnosis

Endometrial biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Findings associated with endometrial cancer include hyperplastic, abnormal glands with vascular invasion.

Serum studies may show an elevation of the CA-125 tumor marker. Remember that tumor markers are not diagnostic, but are useful for monitoring response to therapy.

In a patient where the suspicion for endometrial cancer is very high but the endometrial biopsy is normal, hysteroscopy with biopsy should be performed to visualize the uterine cavity and take additional samples.

A chest X-ray and CT can be used to detect the presence of metastases and ultrasound can be used to detect cervical masses and measure endometrial wall thickness.

Treatment

Regardless of stage, endometrial cancer can be treated with total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH-BSO).

According to NCCN guidelines, if fertility is desired, patients with grade I endometrial cancer limited to the endometrial lining (stage IA) can be treated with the following:

continuous progestins AND

D&C or endometrial biopsy every 3-6months AND

TAH-BSO once childbearing is complete

If an endometrial tumor cannot be completely surgically resected, it should be debulked.

If the endometrial cancer is high-grade or the tumor has invaded beyond the endometrial lining, adjuvant radiation therapy is indicated in addition to surgery. Chemotherapy is indicated for use in any case where endometrial cancer has spread beyond the uterus.

Patients who cannot be cured by surgery and radiation may show benefit from the use of hormone therapy using progesterone.

Complications

Complications of endometrial cancer include:

Local extension to fallopian tubes, ovaries, and cervix

Metastases to the peritoneum, pelvic lymph nodes, aortic lymph nodes, lungs, and vagina

96% 5-year survival rate if local, but 25% 5-year survival rate if metastases are present

Lynch

3-5% of endometrial cancers are due to Lynch syndrome. Remember from Step 1 that Lynch syndrome is associated with defects in mismatch repair genes, and patients have a 40-60% lifetime risk of endometrial and colon cancer. According to the Society for Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), all patients with endometrial cancer should be screened for Lynch syndrome through either a systematic family history or universal tissue genetics from all endometrial cancers.

A family history suggestive of Lynch syndrome includes:

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) diagnosed at age < 50

Synchronous or metachronous CRC or other Lynch syndrome-associated tumors, regardless of age;

CRC with high microsatellite instability on tumor immunohistochemistry in a patient less than 60 years old;

CRC diagnosed in a patient with two or more first-degree or second-degree relatives with Lynch syndrome-associated tumors, regardless of age

CRC diagnosed in a patient with at least one first-degree relative with an HNPCC-related tumor before the age of 50

Note: An older (but easier to remember) version of these criteria is the Amsterdam II criteria, which led to the famous 3-2-1 rule: 3 or more relatives with an associated cancer (colorectal, endometrial, small intestine, ureter, or renal pelvis) 2 or more successive generations affected 1 or more relatives diagnosed before the age of 50 years 1 should be a first-degree relative of the other two

Last updated