01 Ethics

End of Life

Living will

A living will is a document that describes the medical decisions a patient would like to have done in the event that a patient becomes incapable to make decisions due to their medical condition and/or level of consciousness.

A living will typically overrides contrary decision making preferences of the next of kin unless the patient discussed his/her desired treatment options that were contrary to his/her living will with his/her durable power of attorney prior to becoming incapacitated.

Power of Attorney

A durable power of attorney is a legally appointed surrogate who is entitled to make health care decisions for a third party.

An important distinction between the decision that can be guided by a living will and a durable power of attorney is that a living will is limited only to informing decisions for terminal illnesses; whereas, a durable power of attorney is able to make all health care decisions for a third party.

Advanced Planning

Advanced planning is the clinical process in which physicians discuss goals, possible outcomes, wishes and beliefs with patients and their families in order to inform medical decision making.

DNR, DNI

Hospitals must provide patients with the capability of making documentable advanced directives, which include:

Do not resuscitate (DNR)

Do not intubate (DNI)

Withholding of life-sustaining care occurs when physicians do not initiate treatment, such as mechanical ventilation, for a patient who is likely to die according to patient and family wishes; whereas, withdrawal of life-sustaining care occurs when physicians terminate treatment according to decisions made by patients or their families.

Physicians reserve the right to not provide futile treatment, which is defined as a treatment with a less than 1% survival benefit or will likely prolong life by less than 6 weeks.

Medical Errors

Safety culture

The goal of a safety culture is to minimize adverse events and patient harm by creating an environment in which safety concerns can be discussed and brought up by all individuals. This allows for anticipation of errors identification and prevention of poor outcomes.

Healthcare organizations use safety culture assessments to measure organizational conditions that lead to adverse events. Safety culture assessments raise awareness, help track change over time, and create internal and external benchmarks.

Human Factors Design

The goal of the human factors design is to construct healthcare systems that improve the performance of healthcare professionals and reduce hazards. This can be achieved by implementing:

Forcing functions

Standardization

Simplification

In human factors design, forcing functions are design factors that inherently prevent adverse events from occurring. An example of a forcing function is that an intravenous medication syringe is designed so that it will not connect to a nasogastric feeding tube.

Examples of standardization in human factors design include:

Checklists, such as newborn assessment and discharge lists

Protocols, such as the management of diabetic ketoacidosis

Algorithms, such as the workup of abnormal lab values or imaging results

Timeouts before procedures

Examples of simplification in human factors design include:

Eliminating unnecessary steps and paperwork

Removal of unneeded contents in procedure kits

Consolidation of the electronic medical record

Quality Measurement

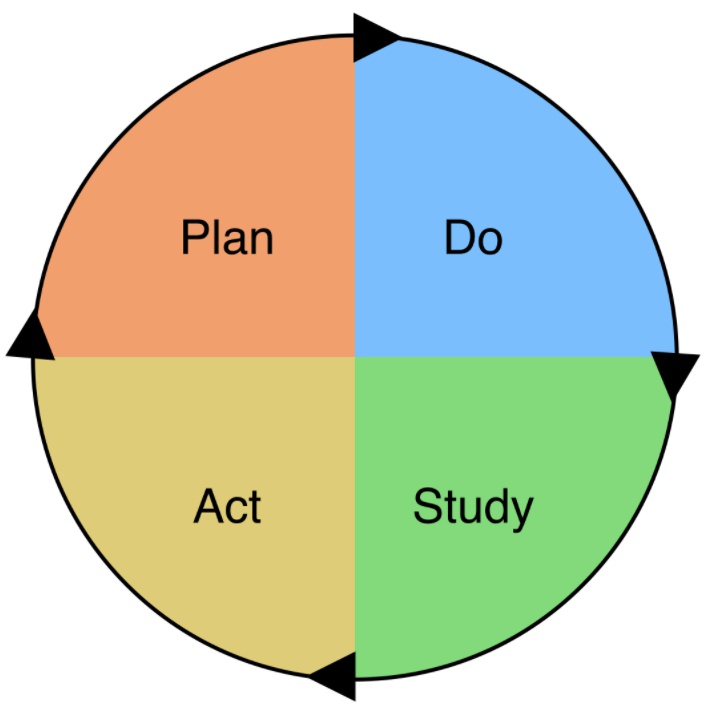

PSDA

The PDSA cycle is used to test quality improvement changes in a healthcare setting. The steps are:

Plan: Establish the area of desired improvement and potential processes that may deliver results with an expected goal or target.

Do: Implement and test the plan or process.

Study: Evaluate the results of the new plan or process compared to target results.

Act: If the results are an improvement from previous processes, they become the standard.

Charts

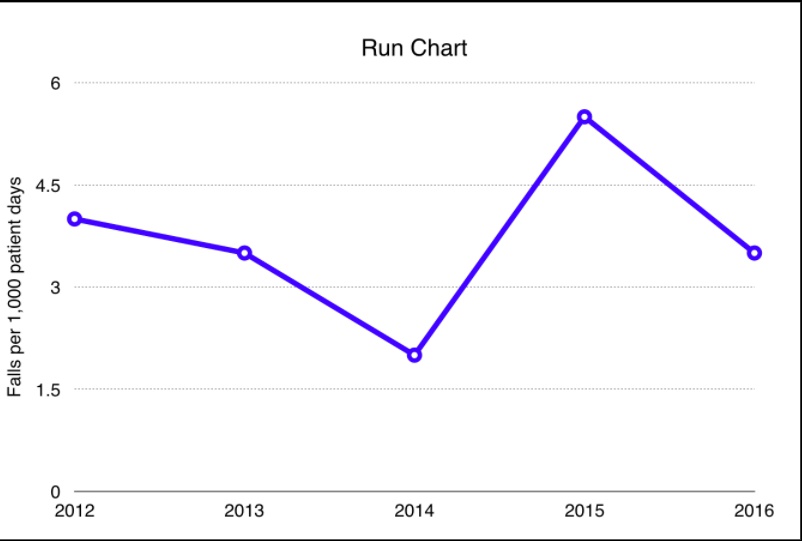

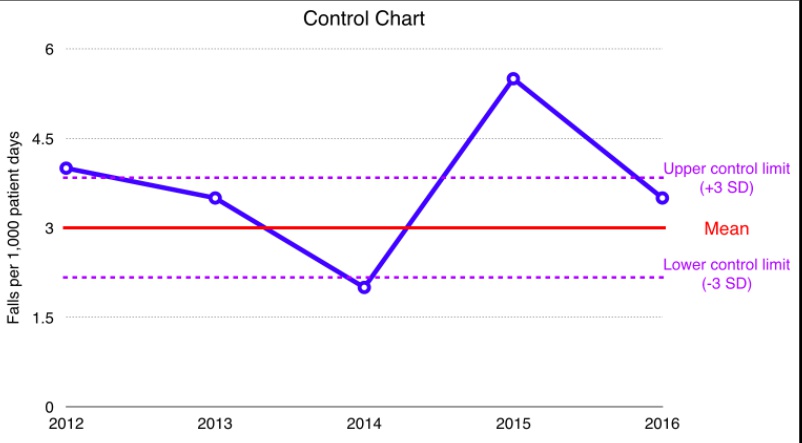

In a health system, quality measurements are typically plotted on control charts and run charts.

run charts: trends

control charts: run charts + mean, upper and lower limits

The three types of healthcare system quality measures are balancing measures, outcome measures and process measures.

Outcome measures evaluate how the system impacts patients, their well-being, and health, as well as the impact on other stakeholders in the system. (For example, in the ICU, what was the adjusted mortality rate per 1000 patients?)

Process measures determine how the parts of the health care system are performing together, and how efforts to improve are being tracked. (For example, in the ICU, is rounding done effectively and in a timely manner?)

Balancing measures determine how changes in one part of the system may cause problems in the other parts of the system. Changes to one part of the system are evaluated from different perspectives. (For example, in the ICU, how are readmission rates affected by changes in discharge criteria?)

Swiss Cheese Model

In the Swiss Cheese model of system failures, hazards are stopped from causing harm by a series of barriers. Each barrier has weaknesses, or “holes,” that open and close at random. When all of the holes in a series of barriers align, then the hazard is able to cause patient harm.

Medical Errors

All errors resulting in harmful outcomes must be disclosed to patients.

Active errors involve frontline personnel committing mistakes.Examples include:

Administration of an incorrect dose of medication

Accidentally cutting the wrong structure during a procedure

Unclear handwriting on a prescription resulting in incorrect medication administration

Latent errors are failure of organization or design that allow inevitable active errors to happen - they are “accidents waiting to happen.” Examples include:

Similar sounding drugs are together in a hospital formulary

System bugs and crashes on the electronic medical record

Necessary equipment and tools for trauma are not stored near the trauma bay

Root Cause Analysis

Root cause analysis identifies errors retrospectively by using all records and interviews with participants involved in the error. For example, after a patient in the intensive care unit dies from an unrecognized and untreated heart attack, all participants are interviewed, records of the surrounding events are analyzed, processes and protocols are evaluated, and environmental factors (room design, etc.) are studied.

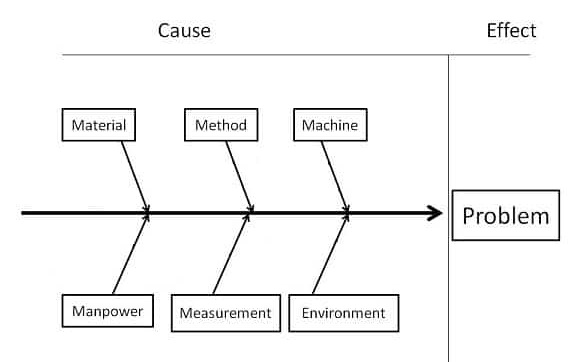

The results from root cause analyses are plotted on fishbone diagrams, which are also called Ishikawa and cause-effect diagrams.

Errors uncovered by root cause analysis should be fixed with a corrective action plan.

Failure Mode

Failure mode identifies errors prospectively by applying inductive reasoning to predict all of the ways a system might fail and cause an error. For example, to avoid unrecognized pulmonary emboli in postoperative patients, nursing staff is instructed to check vitals and ask about symptoms frequently, patients are instructed to get out of bed periodically, and compression devices are placed on the patient's legs.

Last updated