02 Pulmonary

Ventilation

Measurement of airway pressures can be useful in mechanically ventilated patients. The peak airway pressure (the maximum pressure measured as the tidal volume is being delivered) equals the sum of the resistive pressure (flow x resistance) and the plateau pressure.

Peak airway pressure = resistive pressure + plateau pressure

The plateau pressure is the pressure measured during an inspiratory hold maneuver, when pulmonary airflow and thus resistive pressure are both 0. It represents the sum of the elastic pressure and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP).

Plateau pressure = elastic pressure + PEEP

Elastic pressure is the product of the lung's elastance and the volume of gas delivered. Because elastic recoil is inversely related to lung compliance, the elastic pressure can be calculated as tidal volume/compliance. Decreased compliance (eg, pulmonary fibrosis) causes stiffer lungs and higher elastic pressure.

Increased peak pressure associated with an unchanged plateau pressure suggests a pathological process causing increased airway resistance, such as bronchospasm, mucus plug, or endotracheal tube obstruction (Choice B). Elevation of both peak and plateau pressures indicates a process causing decreased pulmonary compliance, such as pulmonary edema, atelectasis, pneumonia, or right mainstem intubation.

Pulmonary Function

Tidal volume is the volume of air inspired (and then expired) during normal respiration.

Inspiratory reserve volume is the volume of air that can be inspired after tidal volume with maximal inspiration.

Residual volume is the volume of air that is left in the lungs after a forceful exhalation.

Expiratory reserve volume is the amount of air that can be forcefully exhaled after normal tidal volume expiration.

Inspiratory capacity is the sum of tidal volume and inspiratory reserve volume (TV+IRV).

Functional reserve capacity is the sum of expiratory reserve volume and residual volume (ERV+RV).

Functional vital capacity is the total sum of expiratory reserve volume, tidal volume, and inspiratory reserve volume (TV+ERV+IRV). It is the maximum amount of air that can be inhaled after completely exhaling forcefully.

Total lung capacity is the sum of vital capacity plus residual volume (VC+RV). It is the total lung volume.

FEV1/FVC is the ratio of the volume of air exhaled in the 1st second of a forceful exhalation to the functional vital capacity. A normal FEV1/FVC ratio is 80%.

In obstructive lung diseases, the FEV1/FVC ratio is typically less than 80%.

In restrictive lung disease, the FEV1/FVC ratio is greater than 80%.

The A-a (alveolar-arterial) gradient is the difference between the partial pressure of oxygen in the alveoli (PAO2) and the arterial (PaO2) circulation. A normal A-a gradient is generally 5-15 mm Hg, and can be estimated by age using the formula (Age/4) + 4. In order to calculate the A-a gradient, a few other variables need to be figured out.

The FiO2 is the fraction of O2 that is in inspired air. When we inhale we bring in water, and other gases in addition to oxygen. The normal FiO2 of room air at sea level is 0.21.

The PAO2 is calculated using the following equation: $PAO_2=[F_iO_2(P{atm}-PH_2O)]-(P_aCO_2/0.8)$

The A-a gradient can be increased in:

Pulmonary edema

Pulmonary embolism

Right to left vascular shunts

A normal A-a gradient in a hypoxic patient can either be due to alveolar hypoventilation or low atmospheric pressure at high altitudes. In such patients, the A-a gradient is said to be "falsely-normal".

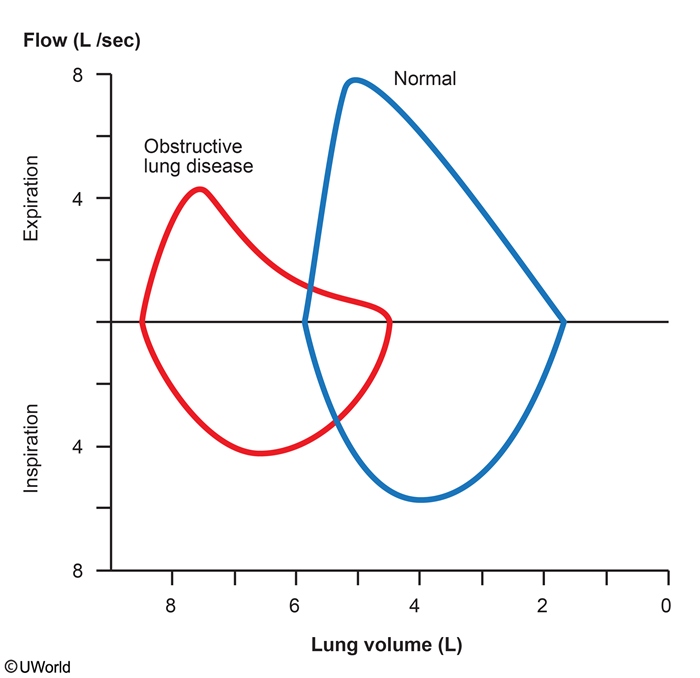

Flow-Volume

One important, perhaps the most important, use of the flow-volume loop is to determine whether the upper airway is obstructed. To assess the presence and the site of upper airway obstruction, two physiologic principles are worth considering. First, expiration and inspiration affect airways differently depending on whether the airway is inside the thorax (intra-thoracic) or outside the thorax (extra-thoracic). If airways are inside the thorax, they are pulled open during inspiration by the negative pleural pressure, thus leading to an increase in airway lumen (and therefore a decrease in resistance to airflow). During forced expiration, however, positive pleural pressure compresses any airways inside the thorax, reducing airway diameter. Consequently, for airways within the thorax (essentially all airways except the upper part of the trachea) resistance to airflow is always greater during expiration than during inspiration.

In contrast, in extra-thoracic airways, (mainly the part of the trachea that is outside the thorax along with the upper airway/epiglottis) inspiration causes a negative pressure within the trachea causing it to narrow. During expiration, the intraluminal pressure becomes positive, making the airway diameter larger. Think of drinking a thick milkshake with a straw, sucking in while taking a drink will cause the internal lumen of the straw to narrow, increasing resistance, blowing in the straw will cause the straw's lumen to widen decreasing resistance. This is the behaviour of the portions of the airway that are outside the thorax.

Three categories of upper airway obstruction may be defined on the basis of the flow- volume loop: 1) fixed obstruction, 2) variable intra-thoracic obstruction, and 3) variable extra- thoracic obstruction (you need to know these).

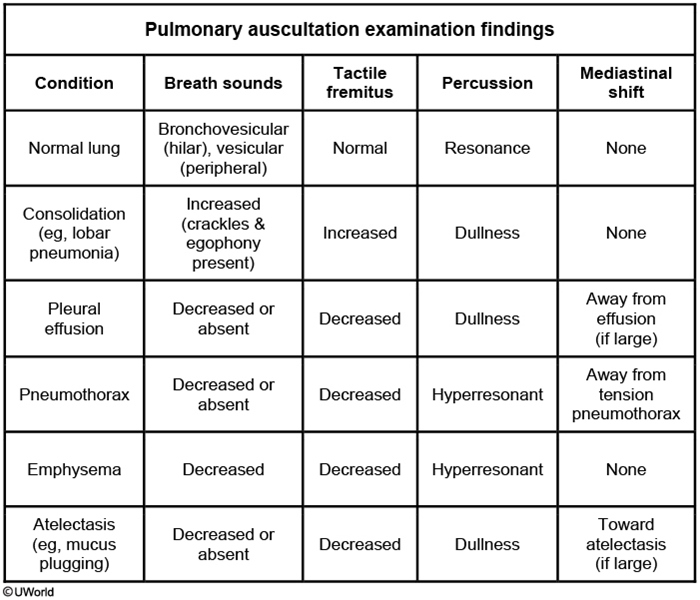

Pulmonary Exam

Respiratory Acidosis

Respiratory acidosis is defined as a serum pH < 7.37 with an increase in pCO2 (>45).

The basic cause of respiratory acidosis is hypoventilation, which can result from:

Depression of the respiratory centers in the CNS

Neuromuscular failure (e.g. myasthenia gravis)

Decreased respiratory system compliance (restrictive lung disease)

Increased airway resistance (obstructive lung disease)

Increased dead space

In respiratory acidosis, look for the following general values:

pH

[H+}

[HCO3-]

pCO2

Compensation

decreased

increased

increased

increased

Increased HCO3 reabsorption

Symptoms of respiratory acidosis result from the change in CSF pH, and include:

Restlessness

Headache

Hyperreflexia

Asterixis

Coma

Paradoxically, NaHCO3 should not be given in cases of pure respiratory acidosis. The HCO3- combines with H+ in tissue, forming CO2 and H2O. If ventilation is not fixed, the CO2 cannot be exhaled, and the hypercapnea worsens.

Respiratory Alkalosis

Respiratory alkalosis is defined as a pH > 7.43 with a decrease in pCO2 (< 35).

The general cause of respiratory alkalosis is hyperventilation, which can be seen in:

CNS stimulation

Hypoxemia

Anxiety

In respiratory alkalosis, look for the following general values:

pH

[H+}

[HCO3-]

pCO2

Compensation

increased

decreased

decreased

decreased

Decreased HCO3 reabsorption

Symptoms of acute respiratory alkalosis include:

Lightheadedness

Impaired consciousness

Seizures

Arrhythmias

Chronic respiratory alkalosis is usually asymptomatic since there is adequate time to adjust to the rising CSF pH.

Increased pH can result in hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, and hypokalemia.

The treatment of respiratory alkalosis involves addressing the underlying etiology.

In the ICU, patients on ventilators can have their ventilation settings (respiratory rate and tidal volume) decreased.

Obstructive

Chronic Bronchitis

Chronic bronchitis is a clinical condition related to COPD that is highly associated with tobacco use and less commonly chronic asthma. It can be diagnosed when a patient experiences a productive cough for greater than 3 months out of the year for more than 2 consecutive years.

Patients with chronic bronchitis are referred to as “blue bloaters” as they:

Experience hypoxia early in the clinical course

Have chronic elevations of PaCO2

Are usually obese

Have peripheral edema or an enlarged liver due to right heart failure

Patients with chronic bronchitis present with:

History of chronic, worsening productive cough

Diffuse, bilateral wheezes

Rhonchi

The diagnosis of chronic bronchitis is clinical, based on a thorough physical exam and patient history.

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) can aid in the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis. PFTs in patients with chronic bronchitis show an obstructive pattern:

Decreased FEV1

Decreased FEV1/FVC ratio

Increased TLC

Increased RV

Chronic bronchitis can be differentiated from emphysema using the DLCO, which is normal in patients with chronic bronchitis and decreased in patients with emphysema. The DLCO measures the extent to which oxygen passes from the air sacs of the lungs into the blood and is decreased in emphysema due to the loss of alveoli.

Infection is the most commonly identified cause of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.

Treatment for acute exacerbations is similar to treatment of asthma exacerbations and involves the use of:

Bronchodilators

Antibiotics

Corticosteroids

Treatment for chronic bronchitis involves management of symptoms:

Antitussives/expectorants

Inhaled β2-agonists

Inhaled anticholinergics

Combined β-agonist and anticholinergic inhalers

Smoking cessation is key to improving the patient’s symptoms and halting the progression of chronic bronchitis to COPD.

Long term complications of chronic bronchitis include:

Emphysema

COPD

Cor pulmonale

Emphysema

Emphysema results from a permanent enlargement of acini along with destruction of the airspace walls. When airflow obstruction also exists, it is classified as COPD.

Emphysema & chronic bronchitis are two types of COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease).

The three types of emphysema are:

Proximal acinar

Panacinar

Distal acinar

Proximal acinar (aka centrilobular) emphysema is the destruction of the respiratory bronchiole, the most central portion of the acinus.

Proximal acinar emphysema is commonly associated with cigarette smoking.

Panacinar emphysema is the destruction of the entire acinus.

Panacinar emphysema is commonly associated with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Distal acinar (aka paraseptal) is destruction of the alveolar ducts, the distal part of the acinus.

Distal acinar emphysema can cause a spontaneous pneumothorax.

Emphysema usually presents with dyspnea, chronic cough, and sputum production.

Hypercapnia and hypoxia occur late in emphysema patients, giving them the name “pink puffers”, because they are pink (not hypoxic) puffers (pursed lips).

Breathing through pursed lips increases airway pressure & keeps airways open.

Patients present with a barrel chest, use of accessory muscles of respiration, JVD, end-expiratory wheezing, and diffusely decreased breath sounds.

CT scan & Pulmonary Function Tests are the best diagnostic tests of emphysema.

CT scan is highly sensitive & specific for emphysema. It can differentiate between the three different types of emphysema.

Pulmonary function tests are consistent with obstructive lung disease, and show low FEV1/FVC ratio, normal/low FVC, normal/high TLC.

DLCO (diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide) is low due to the destruction of alveolar walls.

X-ray findings of the chest suggestive of emphysema include:

Hyperinflation manifested as

Increased retrosternal airspace

Flattening of the diaphragm

Bullae (radiolucent area larger than 1 cm in diameter)

Prominent hilar vascularity (seen in advanced COPD)

All emphysema patients under the age of 40 should be screened for alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency by checking an alpha-1-antitrypsin level.

Emphysema, like any COPD, can lead to secondary pulmonary hypertension.

Emphysema is treated medically, except in severe cases. Surgery is only indicated if aggressive medical management and pulmonary rehabilitation fail.

Medical management of any COPD, including emphysema, can be remembered with the mnemonic “COPD”:

Corticosteroids

Oxygen

Prevention

Dilators

Oxygen can be administered for acute attacks if the oxygen saturation is less than 89%. Intubation and BiPAP ventilators may be necessary, depending on the severity of the attack.

Prevention of disease progression and complications is an important aspect of emphysema management. Patients should be counselled on smoking cessation. They should also be offered pneumococcal and influenza vaccines.

Dilators such as beta-2-agonists and anticholinergic inhalers can be useful in acute attacks.

Lung volume reduction surgery can be performed if medical management fails.

Alternative treatments for refractory emphysema include theophylline and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (e.g. roflumilast).

Emphysema is separated into 4 categories, A-D, based on the patient’s symptom severity & FEV1. The GOLD criteria are determined by the patient’s FEV1 (GOLD, Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease)

Category

FEV1

Symptoms

Treatment

A

> 50% of normal (GOLD I, II)

Infrequent or mild (short of breath on exercise)

Short acting bronchodilators, as needed.

B

> 50% of normal (GOLD I, II)

Frequent or severe (short of breath on normal activity)

Long acting bronchodilator

C

< 50% of normal (GOLD III, IV)

Infrequent or mild (short of breath on exercise)

Long acting beta agonist and inhaled glucocorticoid

D

< 50% of normal (GOLD III, IV)

Frequent or severe (short of breath on normal activity)

Long acting beta agonist, inhaled glucocorticoid, long acting anticholinergic

Category A: Patients have infrequent or mild symptoms, and have an FEV1 greater than 50% of normal (GOLD I or II). These patients are treated with short acting bronchodilators as needed (e.g. albuterol).

Category B: Patients have frequent or severe symptoms, and have an FEV1 greater than 50% of normal (GOLD I or II). These patients are treated with a long-acting bronchodilator (e.g. tiotropium, salmeterol).

Category C: Patients have infrequent or mild symptoms, and have an FEV1 less than 50% of normal (GOLD III or IV). They are treated with a combination long-acting beta agonist and inhaled corticosteroid (e.g. salmeterol, beclomethasone). Alternatively, a long-acting anticholinergic (e.g. tiotropium) is acceptable.

Category D: Patients have frequent or severe symptoms and have a FEV1 less than 50% of normal (GOLD III or IV). They are treated with a combination of:

Inhaled corticosteroids (e.g. beclomethasone)

Long-acting beta agonist (e.g. salmeterol)

Long-acting anticholinergic (e.g. tiotropium)

AAD

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is an inherited defect in a protease inhibitor that may cause emphysema and liver failure, especially in a young person.

Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency typically present in their 30s or 40s with:

Panacinar emphysema (e.g. shortness of breath, wheezing, cough)

Liver disease (e.g. coagulopathy, portal hypertension, encephalopathy)

Skin disease (e.g. panniculitis)

The degree of symptoms for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is dependent upon the genotype:

PiMM is normal

PiSM has reduced protein levels, but no symptoms

PiSZ has reduced protein levels, predisposed to lung disease

PiZZ has markedly reduced or absent protein levels and the highest risk for lung, liver, and skin pathology

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is inherited in an autosomal co-dominant pattern, requiring both M alleles to make alpha-1 antitrypsin.

Diagnosis

For a patient with suspected alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, the next best step in diagnosis is checking for decreased serum levels of alpha-1 antitrypsin.

The diagnosis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency can be supported with a chest x-ray or chest CT scan demonstrating panacinar emphysema.

For alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, the pulmonary function tests will show findings consistent with obstructive lung disease:

Reduced FVC

Reduced FEV1:FVC (< 80%)

Management

The most efficient way of treating alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency involves intravenous augmentation via infusion of pooled human AAT (alpha-1 antiprotease).

Advanced cases of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may require lung or liver transplantation.

Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency must avoid cigarette smoking to prevent rapid progression of lung disease.

Complications include:

Premature development of emphysema

Pneumothorax

Pneumonia

Bronchiectasis

Respiratory failure

Cirrhosis

Liver cancer

Liver failure

Panniculitis

COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a disease of chronic obstruction of airflow that interferes with normal breathing and is not fully reversible.

It is a broader, clinical classification of two distinct pathological processes: emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

The greatest risk factor is cigarette smoking. Acute episode can be triggered with URI

Other risk factors include:

Exposure to pulmonary irritants

Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency

Asthma

The protease-antiprotease hypothesis is thought to play a major role in the pathogenesis. There are many individual pathogeneses of COPD listed below, but they all come down to a relative increase in elastase activity (which breaks down connective tissue in the lungs) as compared to α1-antitrypsin activity (which inactivates elastase).

Nicotine and smoke derived free radicals cause accumulation of PMNs and macrophages in the alveoli. Activated PMNs release proteases, resulting in tissue damage.

Smoking also enhances macrophage elastase activity, which is not susceptible to cleavage by α1-antitrypsin.

Smoking derived free radicals can disrupt the balance between proteases and anti-proteases by inactivating α1-antitrypsin, leading to a "functional" α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Physical exam findings show signs of obstruction and hyperinflation:

“Barrel chest” (increased AP diameter)

Diminished breath sounds

Hyperresonance on percussion

Prolonged expiration with “pursed lips” breathing→ sudden expiration may cause atelectasis due to rapidly decreased alveolar pressure.

Breath sounds heard on auscultation include wheezes (usually end expiratory) from obstruction or crackles (usually inspiratory) from opening of collapsed alveoli.

Diagnosis

The definitive diagnostic tests for COPD are PFTs (pulmonary function tests).

Some supporting evidence for a diagnosis of COPD include anatomical findings of hyperinflation with an obstructive pattern, and systemic findings of hypoxemia and hypercapnia.

PFTs show an obstructive pattern:

Decreased FEV1

Decreased FEV1/FVC ratio

Decreased VC

Normal DLCO in chronic bronchitis vs decreased DLCO in emphysema

Increased TLC, RV, FRC (from trapped air)

Chronic respiratory acidosis (from increased air trapping and an inability to blow off carbon dioxide) leads to chronic metabolic alkalosis, which is indicated by elevated pCO2 and bicarbonate.

Polycythemia may occur in response to chronic hypoxemia as a compensatory response in order to increase oxygen carrying capacity in the blood.

CXR (chest x-ray) shows characteristic hyperlucent lung fields. Air trapping can lead to flattening of the diaphragm. In severe disease the heart can also become elongated and tubular shaped as a result of the increased air in the thorax.

The most common complication of COPD is referred to clinically as a COPD exacerbation. This is an acute episode of worsening of pulmonary function from baseline most commonly due to upper respiratory infection, air pollution, cardiac disease, or non-compliance with medication. COPD exacerbations often require hospitalization and mechanical ventilation.

Death is most commonly due to:

Respiratory acidosis and hypercapnic respiratory failure

Cor pulmonale (rare)

Massive spontaneous secondary pneumothorax

Cor pulmonale (right heart failure) occurs as a result of hypoxia (hypoxia leads to vasoconstriction of pulmonary arterioles, which increases afterload and can eventually lead to right ventricular failure).

Treatment

Treatment goals are to reduce obstruction by dilating the airways and reducing mucus secretion, and prevention of disease progression.

Interventions shown to decrease mortality in patients with COPD are:

Smoking cessation

Supplemental oxygen

At least 15-18 hours/day in order to titrate SaO2 to 90-92%

Smoking cessation is critical. Does not reverse disease, but rate of respiratory function decline reverts to that of a non-smoker. Avoid other pulmonary irritants that will increase mucus production → allergens and asphyxiants (i.e. industrial chemicals).

Inhaled β2-agonists act as bronchodilators and provide symptomatic relief. Long acting β2-agonists such as salmeterol are often used.

Inhaled anticholinergic drugs such as ipratroprium bromide also act as bronchodilators and decrease symptoms. They have a slower onset of action than β-agonists but have a longer duration.

Note: Combined β-agonist and anticholinergic inhalers (such as albuterol-ipratroprium bromide) are more effective than either alone.

Inhaled corticosteroids are only recommended for patients with severe COPD and those with frequent exacerbations not controlled by long-acting bronchodilators.

The indications for long-term oxygen therapy for patients with COPD include:

Severe hypoxemia; defined as either:

PaO2 ≤55 mmHg

SpO2 ≤88%

--OR--

Moderate hypoxemia (PaO2 ≤59 mmHg or SpO2 ≤89%) PLUS either:

Cor pulmonale/right heart failure

Erythrocytosis (hematocrit >55%)

Managing acute COPD exacerbations requires the following interventions:

Supplemental oxygen titrated to goal (SpO2) of 88 to 92%

Inhaled bronchodilators (e.g. albuterol, ipratropium)

Intravenous glucocorticoids

Antibiotics if the patient has at least 2 out of 3 cardinal symptoms:

Increased dyspnea

Increased sputum volume

Increased sputum purulence

The indications for noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) are the following:

Severe dyspnea with respiratory muscle fatigue

Increased work of breathing

Arterial pH ≤7.35

PaCO2 ≥45 mmHg

Asthma

Asthma is a common, reversible obstructive lung disease characterized by airway hyper-responsiveness and obstruction with underlying inflammation.

Physiologic causes of acute asthma exacerbations include:

Infections

Exercise

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Emotional stress

Pharmacologic agents that can precipitate an acute asthma exacerbation include:

NSAIDs (e.g. aspirin)

β -blockers (e.g. propanolol)

Cholinomimetics (e.g. bethanechol)

Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease refers to the combination of:

Asthma

Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

Respiratory tract reactions to aspirin and other NSAIDs that inhibit COX-1

These features are also known as Samter’s triad.

Environmental causes of acute exacerbations include:

Dust mites

Animal and cockroach allergens

Pollen

Environmental pollutants

Tobacco smoke

Occupational exposure

Cold air

Risk factors for asthma include:

Family history

History of atopy

Low socioeconomic status

The inflammatory response of asthma is thought to include:

Production of specific IgE antibodies, often triggered by environmental influence

Binding of IgE to mast cells

Allergens cross-linking IgE on mast cells, which leads to mast cell degranulation

Airflow obstruction in asthma is caused by:

Acute bronchoconstriction

Airway edema

Chronic mucous plug formation

Airway remodeling

The major inflammatory cells involved in asthma include:

Mast cells

Eosinophils

TH2 lymphocytes

The classic symptoms of asthma areintermittent dyspnea, episodic cough, and wheezing.

Symptoms often worsen at night.

The diagnosis of asthma is based upon history of symptoms(intermittent dyspnea, episodic cough, and wheezing), with demonstration of reversible airflow obstruction.

Physical exam during an asthma exacerbation can reveal:

Decreased O2 saturation

Tachycardia

Tachypnea

Decreased breath sounds

Wheezing

Accessory muscle use

Wheezing may be absent if airflow is severely limited.

Spirometry should be used as the primary test to establish an asthma diagnosis.

Patients have a reduced FEV 1 to FVC ratio (demonstrating airway obstruction), which is reversible with an inhaled bronchodilator.

A methacholine challenge test can be administered to a patient who has normal spirometry results. A 20% decrease in FEV 1 after administration of methacholine indicates a positive result for bronchial hyperresponsiveness.

CBC can show eosinophilia.

Chest x-ray is usually normal, but may show hyperinflation.

Acute asthma exacerbations can be complicated by:

Severe hypoxemia

Hypercapnia

Respiratory acidosis requiring intubation and ICU management

Treatment

The treatment for an acute asthma exacerbation includes:

Supplemental oxygen to maintain SpO2 ≥90%

Inhaled albuterol (β2 agonists increase airway diameter)

Systemic corticosteroids (decrease airway inflammation)

Severe exacerbations may require:

Inhaled ipratropium bromide

Intravenous magnesium sulfate

Exacerbations that are refractory to treatment, with impending respiratory failure, require intubation and ICU management.

Long-term management is focused on achieving and maintaining control over symptoms, maintaining normal activity levels, and preventing exacerbations.

Intermittent asthma is defined as having:

Symptoms ≤2 days/week

≤2 night time awakenings per month

Use of a short acting β agonist ≤2 days/week

No interference with normal activity

FEV1 >80% predicted

Intermittent asthma is managed with quick-acting inhaled β2 agonists (e.g. albuterol) taken as needed for relief of symptoms.

Mild persistent asthma is defined as having:

Symptoms >2 days/week but not daily

3-4 night time awakenings per month

Use of a short acting β agonist >2 days/week but not daily

Minor interference with normal activity

FEV1 ≥80% predicted

Mild persistent asthma is managed with daily low dose inhaled glucocorticoids, as well as quick-acting inhaled β2 agonists taken as needed for relief of symptoms.

Moderate persistent asthma is defined as having:

Symptoms daily

Night time awakenings >1x/week but not nightly

Daily use of a short acting β agonist

Some interference with normal activity

FEV1 >60 but <80% predicted

Moderate persistent asthma is managed with:

Low or medium doses of an inhaled glucocorticoid

Long-acting inhaled β2 agonists

Symptomatically,quick-acting inhaled β2 agonists

Severe persistent asthma is defined as having:

Symptoms throughout the day

Night time awakenings up to 7x/week

Use of a short acting β agonist several times a day

Significant interference with normal activity

FEV1 <60% predicted

Severe persistent asthma is managed with:

Medium or high doses of an inhaled glucocorticoid

Long-acting inhaled β2 agonist

As needed, quick-acting inhaled β2 agonists

Agents used to treat aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease include:

1st line: leukotriene-receptor antagonists:

Montelukast

Zafirlukast

2nd line: 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor:

Zileuton*

*Zileuton is considered a second-line agent (in part) due to a risk of hepatotoxicity.

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis is a permanent dilation of bronchi caused by recurrent cycles of infection/inflammation leading to fibrosis and remodeling.

Certain pathologies put a patient at risk of developing bronchiectasis, all being causes of recurrent bronchial inflammation.

Cystic fibrosis (accounts for about 50% of all cases)

COPD

Airway hypersensitivity diseases

Primary ciliary dyskinesia

Immunodeficiency

Autoimmune disease

Localized airway obstruction

Recurrent pulmonary infections or recurrent aspiration

Bronchiectasis can be a cause of secondary amyloidosis. Suspect secondary amyloidosis in a patient with concurrent bronchiectasis and chronic renal failure with elevated urine protein.

Patients with bronchiectasis will have a chronic cough with yellow/green sputum and dyspnea. They may also have hemoptysis.

On physical exam, patient may have rales, wheezes, or rhonchi depending on the cause of bronchial inflammation. These abnormal sounds (especially wheezing) may be heard even when the patient is not having an acute attack.

Bronchiectasis is often confused with chronic bronchitis, which in itself can be a cause of bronchiectasis. In general, bronchiectasis has >100 mL sputum production per day whereas chronic bronchitis has <100 mL per day. Also, sputum is usually purulent in bronchiectasis but is normally non-purulent in chronic bronchitis.

The first imaging test done is usually a chest X-ray, which can show increased bronchovascular markings and tram lines (parallel lines outlining bronchi).

High-resolution CT (HRCT) of the chest is the gold standard for diagnosing bronchiectasis.

On chest CT of a patient with bronchiectasis, the bronchioles are markedly dilated to the point they have a greater diameter than the pulmonary vessels at the same level.

Spirometry will show an obstructive pattern with decreased FEV1/FVC ratio.

There is no direct treatment to reverse bronchiectasis. Treatment mostly consists of treating the underlying disease process leading to airway inflammation (eg. using antibiotics for bacterial infections and inhaled corticosteroids for airway inflammation).

If bronchiectasis is severe enough that sufficient oxygenation is not able to be maintained through other methods, surgery is done. Lobectomy is used for localized disease, and lung transplant is done for severe diffuse disease.

Restrictive

Pneumoconioses

The pneumoconioses are a group of diseases characterized by interstitial fibrosis that is secondary to occupational exposure to mineral dust, metal, nylon, or other inhaled particles.

More common examples of pneumoconioses include:

Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis

Silicosis

Berylliosis

Asbestosis

Talcosis

Pneumoconiosis patients typically have a combination of these historical elements:

Occupation with exposure risk

Shortness of breath

Cough

Tight feeling in the chest

Exposure to smoke

Physical exam findings of a patient with later phases of pneumoconiosis include:

Dyspnea on exertion

Crackles

Wheezing

Focal areas of dullness

Cyanosis

Barrel chest

Finger clubbing

Weight loss

In the early phase of pneumoconiosis, patients will often have a completely normal pulmonary exam.

Pulmonary function tests (PFT) can show evidence for either an obstructive or restrictive disease process with reduced DLCO (diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide).

Complications of pneumoconiosis include:

Connective-tissue disease

Vasculitis

Lung cancer

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Chronic kidney disease with renal failure

Rheumatoid arthritis

Scleroderma

The combination of occupational exposure and cigarette smoke synergistically increases the risk for malignancy and other complications of pneumoconiosis.

Supportive treatment for patients with a pneumoconiosis include:

Oxygen therapy

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Smoking cessation counseling

Pneumoconiosis patients with a PaO2 of less than 60 mm Hg with oxygen therapy should be considered for lung transplant.

Coal Worker

Among coal workers, the current prevalence of coal worker’s pneumoconiosis is 2%.

Chest x-ray (CXR) of coal workers lung will demonstrate many noncalcified and round opacities, and in advanced disease may show thin calcification around hilar lymph nodes.

During post mortem or post surgical resection examination, the lungs of a coal worker’s pneumoconiosis patient would show diffuse blackening of the lung parenchyma.

Caplan syndrome describes the association between rheumatoid arthritis and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis.

Asbestosis

CXR of a patient with asbestosis will demonstrate bilateral lower lobe interstitial fibrosis with pleural thickening.

Biopsy from pleural opacities of asbestosis patients will demonstrate patchy dumbbell shaped ferruginous bodies on histology.

Bronchogenic carcinoma (not mesothelioma!) is the most common cancer associated with asbestosis.

Although less common than lung carcinoma, mesothelioma is a malignancy derived from cells of the pleural lining of the lung that has a strong association with asbestos exposure.

To summarize, while mesothelioma occurs almost exclusively after asbestos exposure, it is not the most common cancer associated with asbestosis.

Silicosis

Some occupations that place workers at risk for silicosis include:

Sand blasters

Miners

Rock quarry workers

Foundry workers

CXR of silicosis in early stages will show nodular,rounded opacities of <1 cm.

In later stages, CXR of silicosis patients will demonstrate coalesced nodules greater than 1 cm in size, hilar lymphadenopathy with calcification, upper lobe fibrosis, and lower lobe hyperinflation.

Berylliosis

Some occupations with a risk for beryllium exposure include manufacturing work in the following sectors:

Aerospace

Electronics

Metal reclamation

Jewelry making

Acute berylliosis presents as pneumonitis with CXR finding of pulmonary edema.

Chronic berylliosis presents as bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy with non-caseating granulomas in peribronchial and perilymphatic regions, thickened septal lines, and ground glass opacities on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT).

A beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test (BeLPT) is diagnostic for berylliosis if positive results are obtained from both a blood sample for screening and a bronchoscopy for confirmation.

Berylliosis is treated with oral corticosteroid therapy.

Cryptogenic Oranizing Pneumonitis

Pneumonitis: Pulmonary inflammation that results in interstitial fibrosis and a restrictive pattern of lung disease.

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis is an idiopathic type of diffuse interstitial lung disease (previously called bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia or BOOP) affecting the structures including and distal to the distal bronchioles (i.e. distal bronchioles, respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveolar walls). The alveolar walls are affected the most.

Patients present with cough, dyspnea, and flu-like symptoms.

CXR shows bilateral, patchy infiltrates.

Treatment of cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis is corticosteroids.

Radiation pneumonitis: Occurs in patients who have received thoracic radiation, usually for treatment of malignancy.

Acute form of disease occurs within one to six months.

Chronic forms occur one to two years later.

CXR may be normal, but also may show perivascular haziness or opacities.

CT shows diffuse infiltrates, ground glass density, and consolidation, with possible pleural or pericardial effusions.

IPF

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is caused by abnormal proliferation of mesenchymal cells, excessive collagen deposition, and disorganization of the extracellular matrix of the lung parenchyma.

Risk factors for IPF include:

Advanced age

Male gender

Occupational exposure

Cigarette smoke exposure

Positive family history

More than 380 drugs are associated with interstitial fibrosis. Notably:

Amiodarone

Amphotericin B

Bleomycin

Busulfan

Chlorambucil

Cyclophosphamide

Methotrexate

IPF presents with the following symptoms:

Weight loss

Fatigue and malaise

Dyspnea on exertion

Dyspnea

Cough

Physical exam findings for IPF patients include:

Crackles

Clubbing of nails

Diagnosis

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the thorax is the preferred diagnostic imaging modality for IPF and will demonstrate pathognomonic honeycombing.

Complications of IPF include:

GERD

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

Pulmonary infections

Respiratory failure

Management

Supportive care is the cornerstone of management for patients with IPF including:

Pulmonary rehab

Supplemental oxygen

Influenza vaccine

Pneumococcal vaccine

A high dose regimen of corticosteroids is the recommended treatment for acute exacerbations of IPF.

Lung transplantation should be considered in IPF patients that experience continued deterioration despite maximal medical management.

Respiratory Infection

Sinusitis

The most common cause of sinusitis is viral infection associated with the common cold or upper respiratory infection (URI).

Causes of acute sinusitis due to obstruction include:

Nasal polyps

Deviated septum

Foreign body

Bacterial infection accounts for less than 2% of cases of sinusitis. The three most common bacteria causing sinusitis are:

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Haemophilus influenzae

Moraxella catarrhalis

Patients with sinusitis may present with:

Sinus congestion

Purulent nasal discharge

Cough

Sinus pain

Sinus pressure

Maxillary sinusitis can present with pain over the cheeks that may mimic the pain associated with dental caries.

Diagnosis depends on physical exam findings including:

Sinus congestion

Purulent discharge

Mucosal edema and inflammation

Pain upon palpation of sinuses (non-specific finding)

Imaging studies including x-ray and CT scan are NOT indicated in the initial evaluation of uncomplicated sinusitis.

CT scan is the imaging modality of choice in patients with complicated sinusitis.

Acute bacterial sinusitis should be suspected if patients with symptoms of sinusitis present with any of the following:

Symptoms lasting > 10 days

Severe pain and fever (> 102° F) lasting more than 3 days

Symptoms that improve and then worsen after several days ("double sickening")

Several complications can occur in patients with sinusitis including:

Orbital cellulitis

Mucoceles

Osteomyelitis

Intracranial infection (eg. epidural abscess, meningitis, brain abscess)

Cavernous sinus thrombosis

Symptoms of sinusitis must be present at least 3 months before a diagnosis of chronic sinusitis can be made. Patients often present with nasal congestion with pain and headache in the absence of fever.

Carries a high risk for infection with Staphylococcus aureus, especially after multiple courses of antibiotics.

Treatment of chronic sinusitis requires the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and referral to an otolaryngologist.

Treatment of acute sinusitis is primarily supportive and aimed at symptom management.

Supportive measures that can be used in patients with acute sinusitis include:

Saline nasal irrigation

Oral decongestants

Mucolytics

Mild analgesics

The first line treatment for patients with suspected acute bacterial sinusitis is amoxicillin-clavulanate.

Antihistamines should NOT be given routinely and are reserved for patients with allergies due to their drying effect which can worsen congestion.

Acute Laryngitis

Acute laryngitis refers to the inflammation of the larynx which lasts for less than three weeks.

Acute laryngitis is commonly the result of:

Viral upper respiratory tract infections

Moraxella catarrhalis

Hemophilus influenzae

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Vocal overuse

Chronic laryngitis refers to inflammation of the larynx persisting for >3 weeks.

Chronic laryngitis may be the result of:

Vocal overuse (e.g. professional vocalists)

Chemical irritation (e.g. occupational and industrial exposures)

Cigarette smoking

Gastroesophageal reflux

Allergic rhinitis or post-nasal drip

Chronic alcoholism

Muscle tension dysphonia

Patients with either acute or chronic laryngitis typically present with:

Vocal hoarseness

Chronic coughing

Dry or sore throat

Painful throat

Viral upper respiratory tract infection symptoms (e.g. rhinorrhea, cough, malaise)

Dyspnea (if swelling is severe, typically in children)

The diagnosis of acute laryngitis is typically made via history and physical examination,whereas chronic laryngitis warrants direct visualization by laryngoscopy.

Acute laryngitis is typically a self limiting process managed through supportive care:

Voice rest to reduce risk of formation of vocal nodules

Throat soothing lozenges

Humidifiers

Warm liquids

The management of chronic laryngitis involves treating the underlying condition, such as:

Smoking cessation

Occupational precautions (e.g. wearing a face mask)

Vocal cord rest

Antibiotics for sinusitis

Ranitidine (Zantac) or omeprazole (Prilosec)

If left untreated, chronic laryngitis may result in:

Permanent loss of voice

Infectious spread (if originally caused by an infection)

Respiratory obstruction requiring intubation

Strep

Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β hemolytic streptococci) is the most common bacterial cause of pharyngitis in children.

Patients with streptococcal pharyngitis classically present with the following symptoms:

Acute onset sore throat

Headache

Nausea and vomiting

Abdominal pain

Odynophagia

Lack of a cough

Tender cervical lymphadenopathy

Streptococcal pharyngitis may be confused with infectious mononucleosis. Infectious mononucleosis typically has the following differentiating symptoms:

1-4 week prodromal period

Hepatomegaly

Splenomegaly

Posterior cervical lymphadenopathy(versus anteriorly located with strept. pharyngitis)

The Modified Centor criteria (also known as the McIsaac score) are used to estimate the probability of Streptococcus pharyngitis and to guide treatment decisions in a patient with a sore throat. One point is given for each of the following:

Fever

Tonsillar exudates

Tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy

Absence of cough

Age <15

Subtract one point for age over 44

Modified Centor criteria scoring may be used in adults to guide a clinician's diagnostic approach:

Centor score < 3 should not be treated or undergo diagnostic testing

Centor score ≥ 3 should undergo rapid antigen detection testing

The gold standard for diagnosing Streptococcal pharyngitis is throat culture, however rapid antigen detection testing (RADT) may be used if symptoms are severe and treatment cannot wait for a culture to grow.

The rapid antigen test is low sensitivity, thus if it is negative and your clinical suspicion remains high, follow up with a throat culture to definitively diagnose.

On physical exam, patients with streptococcal pharyngitis may present with:

Tonsillar erythema and exudates

Swollen uvula

Anterior cervical lymphadenopathy

Petechiae on the palate

Scarlatiniform rash

Management

The management of streptococcal pharyngitis includes:

Oral penicillin V (drug of choice)

Amoxicillin (alternatively to penicillin V)

Erythromycin (if allergic to penicillin)

Intramuscular penicillin G benzathine may be used to treat streptococcal pharyngitis if the patient is unable to tolerate oral antibiotics.

Antibiotic therapy should only be started for streptococcal pharyngitis when either:

Throat culture is positive

A rapid antigen detection test is positive

Centor score is 4 - 5

If left untreated, streptococcal pharyngitis may cause:

Acute rheumatic fever

Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with group A streptococci (PANDAS) syndrome

URI

Upper respiratory infections include any acute infections that involve the upper respiratory tract, which extends from the nasal passage and sinuses, down to the larynx.

Rhinopharyngitis (or the common cold) is typically caused by viruses. Rhinovirus is the cause in up to 50% of cases.

Pharyngitis can be either viral or bacterial in origin; most cases are viral. However, Group A Streptococcus is the most common bacterial cause and must be treated.

Rhinosinusitis is usually caused by a virus. The most common non-viral etiologies, in order, are:

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Haemophilus influenzae

Moraxella catarrhalis

Staphylococcus aureus

Aspergillus (in immunocompromised or diabetic patients)

Viral URIs typically last 7-10 days. Persistent symptoms lasting >10 days is suggestive of a bacterial illness.

Rhinorrhea, congestion and sneezing are early symptoms. Rhinorrhea is more characteristic of a viral infection.

Rhinosinusitis is associated with:

Nasal discharge

Facial or dental pain

Cough

Sore throat

Post-nasal drip

Pharyngeal symptoms include odynophagia (painful swallowing) or dysphagia (difficulty swallowing).

Cough may be due to post-nasal drip, or may be indicative of laryngeal involvement.

Constitutional symptoms can include:

Fever

Fatigue

Malaise

Diagnosis of viral URIs is a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms. The Centor criteria is a symptom based grading system to determine the likelihood of Streptococcal pharyngitis.

Imaging is NOT indicated for routine rhinosinusitis. If symptoms persist despite therapy, or if there are signs of extension of the disease intracranially, sinus imaging with a CT scan may be appropriate.

Complications of URIs necessitating further treatment or hospitalization include:

Bacterial infection or superinfection

Pneumonia

Intracranial abscess

Airway obstruction or occlusion (eg. asthma exacerbations, peritonsillar abscess)

Treatment is largely supportive unless a bacterial infection is suspected in which antibiotic therapy may be warranted.

Viral URIs benefits from reassurance/education and symptom management with:

Decongestants

Analgesics

Antipyretics

For sinusitis, a course of antibiotics is warranted for the following:

Symptoms persisting without improvement for 10 days or longer

Symptoms greater than 5 days after initially improving from a viral URIs

Fever greater than 102 F

Purulent nasal discharge

Facial pain persisting more than 3 days

The antibiotic of choice is amoxicillin-clavulanate, or if patient has a penicillin allergy, consider doxycycline, levofloxacin or moxifloxacin.

Chronic sinusitis requires endoscopic drainage by ENT.

Acute Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis is a self-limited, inflammatory process of the bronchial tree, sparing much of the lung parenchyma. Acute bronchitis typically results from:

Viruses including influenza A + B

Parainfluenza

Less commonly, bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Bordetella pertussis

Risk factors for acute bronchitis include:

Winter months

Cigarette smoke (which paralyzes bronchial cilia)

COPD

Intubation (acute bacterial bronchitis)

Patients typically present with:

Productive cough for > 5 days (from sloughing of bronchial cells)

Typically afebrile or low grade fever

Viral upper respiratory infection symptoms (runny nose, cough, etc).

Wheezing due to bronchospasm

Physical exam demonstrates no signs of consolidation on auscultation of acute bronchitis (vs. pneumonia). The chest X-ray is utilized only to rule out pneumonia and shows clear lungs.

Acute bronchitis may result in pneumonia in patients with underlying chronic lung disease.

Most cases of acute bronchitis do not require treatment, only supportive therapy such as aspirin and ipratropium.

Chronic Cough

Chronic cough, defined as a cough lasting > 8 weeks, is a common complaint in the doctor's office.

The etiologies of a chronic cough may include:

Respiratory infections (e.g. B. pertussis)

Post-URI cough (typically after viral upper respiratory tract infections)

Malignancy (e.g. lung cancer)

Medication

GERD

Asthma

Upper-airway Cough Syndrome

The first step in evaluating patients who are at higher risk for infection and cancer, including smokers, the immune compromised and patients with signs of pneumonia is chest x-ray.

When other causes have been excluded, the three most common etiologies of chronic cough in patients with no identifiable cause are:

Upper-airway cough syndrome (postnasal drip)

GERD

Asthma

*These patients often receive empiric drug therapy targeted at one of the three above diseases; the diagnosis is confirmed upon treatment response.

Upper-airway cough syndrome also known as postnasal drip should be treated empirically with H1 histamine receptor antagonists (chlorpheniramine). The resolution of symptoms in 2-3 weeks is diagnostic for upper-airway cough syndrome.

Dry cough is a possible side effect seen in patient's taking ACE inhibitors due to the buildup of bradykinin. Cessation of the medication and switching to an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) should improve symptoms.

Pneumonia

Infectious agents that cause typical CAP include:

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Haemophilus influenzae

Klebsiella pneumoniae

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Staphylococcus aureus

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of community-acquired pneumonia.

The risk factors for Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia are:

Smoking

COPD

Immunocompromised (i.e. HIV)

Treatment options of Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia includes:

Amoxicillin/Ampicillin

Ceftriaxone/Cefotaxime

Azithromycin

Doxycycline

Levofloxacin/Moxifloxacin

The risk factors for Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia are:

Sickle cell disease

COPD

Smoking

Immunocompromised disorders

Alcoholism

Diabetes

In general, Haemophilus influenzae pneumonia is best treated with a third-generation cephalosporin(ceftriaxoneorcefotaxime).

Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia is seen in:

Alcoholics (classically)

Stroke patients

Elderly

Patients with decreased level of consciousness

Treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae community-acquired pneumonia includes third-generation cephalosporinsorfluoroquinolones.

The risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia are:

Severe structural lung disease such as bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, or severe COPD

Hospitalized patients or nursing home residents

Ventilator-assisted breathing

Patients who have received broad spectrum antibiotics or high-dose steroid therapy

Treatment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia include:

Piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn)

Cefepime (Maxipime)

Imipenem(Primaxin)

Meropenem (Merrem) and a fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin [Cipro] or levofloxacin [Levaquin])

The risk factors for Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia are:

Recent flu or viral illness

Skin colonization or infection withStaphylococcus aureus

Laryngeal cancer

Immunosuppression

Treatments for methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus(MRSA) include linezolid, clindamycin, or vancomycin.

The most common cause of secondary pneumonia following viral pneumonia is S. pneumoniae (about 50% of cases), followed by Staphylococcus aureus.

Secondary pneumonia following viral pneumonia caused by Staphylococcus aureus will commonly present with a cavitary lesion or empyema on chest x-ray

The signs and symptoms of typical community acquired pneumonia (CAP) are:

Acute onset of fever and shaking chills

Productive cough with thick purulent sputum

Pleuritic chest pain

Dyspnea

Tachycardia and tachypnea

Late inspiratory crackles and/or bronchial breath sounds

Increased tactile and vocal fremitus as well as dullness to lung percussion

Pleural friction rub that can indicate pleural effusions

Recurrent Pneumonia

Recurrent pneumonia occurring in the same anatomic location of the lung raises suspicion for localized airway obstruction, which, if present, can lead to impaired bacterial clearance and predisposition to infection (eg, postobstructive pneumonia).

Potential causes of localized airway obstruction include:

External bronchial compression due to lymphadenopathy, expanding neoplasm, or vascular anomaly

Internal bronchial obstruction due to a foreign body, bronchiectasis, bronchial stenosis, or, rarely, endobronchial carcinoid

Smoking is the strongest risk factor for the development of primary lung malignancy. In this patient age >50 with a significant smoking history (30 pack-years) and evidence of localized airway obstruction, it is essential to evaluate for lung malignancy using a CT scan of the chest.

Pneumonia ages

Infectious agents that commonly cause pneumonia from birth to 3 weeks are:

Listeria

GBS (group B strep)

Gram negative bacilli

CMV

Infectious agents that commonly cause pneumonia from 3 weeks to 3 months are:

Chlamydia trachomatis

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Bordetella pertussis

Infectious agents that commonly cause pneumonia from 4 months to 4 years are:

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Streptococcus pneumoniae

GAS (group A strep)

RSV

Infectious agents that commonly cause pneumonia from 5 to 18 years of age are:

Streptococcus pneumoniae

EBV (epstein barr virus)

Staphylococcus aureus

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Chlamydia pneumoniae

Infectious agents that commonly cause pneumonia from 18 to 65 years of age are:

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Chlamydia pneumoniae

Haemophilus influenzae

Influenza virus

Infectious agents that commonly cause pneumonia in those over the age of 65 are:

Legionella pneumonia

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Haemophilus influenzae

Gram negative bacilli

Staphylococcus aureus

Influenza virus

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia

CTEP

chronic thromboembolic: multiple small emboli, leading to PHTN

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasma capsulatum is a genus of dimorphic fungus with septate hyphae that alter with changing temperature:

Mycelial (mold) form at ambient (colder) temperatures

Yeast form at body (warmer) temperatures

Histoplasma capsulatum _is a facultative intracellular yeast (2 - 4 microns in diameter) found inside macrophages. (Mnemonic: Histo Hides within macrophages_).

_Histoplasma capsulatum_is_e_ndemic to the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi River valleys.

_Histoplasma capsulatum_lives in soil and is associated with bird and bat droppings.

Histoplasmosis can cause a pulmonary infection or a disseminated infection.

Disseminated histoplasmosis typically occurs in infants or immunocompromised patients (e.g. AIDS, immunosuppression, chemotherapy)

Patients with pulmonary histoplasmosis are typically asymptomatic but may develop symptoms weeks to months following infection:

Flu like symptoms (e.g. fevers, chills, cough)

Pleuritic chest pain

Severe exposure may cause respiratory failure

Acute exposures can have bronchopneumonia

Chronic exposures may cause centrilobular emphysema

Patients with disseminated histoplasmosis typically present with:

Fever

Weight loss

Hepatosplenomegaly

Lymphadenopathy

Mediastinitis

Fatigue

Pancytopenia

Erythema nodosum

Pericarditis

Gastrointestinal ulcerations

Adrenal insufficiency

Palatal ulcers

The diagnosis of histoplasmosis is dependent upon clinical exam and the _Histoplasma _antigen detection enzyme immunoassay of the serum or urine.

The definitive diagnosis of _Histoplasma capsulatum_is by tissue biopsy of the lung or lymph nodes demonstrating granulomas.

In an immunocompetent patient, the granulomas ofpulmonary histoplasmosis may calcify forming target or bull's eye shapes on chest x-ray which may resemble tuberculosis.

Severely immunocompromised patients infected with Histoplasma capsulatum cannot form granulomas and instead form splenic and liver calcifications, which can be seen on abdominal imaging.

Patients with histoplasmosis who are asymptomatic are treated with supportive therapysince the infection is typically self-limited.

Patients with symptomatic histoplasmosis, but do not require hospitalization, are treated with oral itraconazole.

Patients with histoplasmosis that require hospitalization (e.g. disseminated variants) are treated with IV amphotericin B. Once a clinical response to amphotericin B is achieved, patients can be transitioned to oral itraconazole for 1 year.

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is a systemic pyogranulomatous infection that is caused by inhalation of _Blastomyces_spp. Blastomycosis mostly occurs in North America, with endemic areas in the southeastern and south-central states that border theMississippi and Ohio River basins, Great Lakes,and a small portion of New York and Canada along the St. Lawrence River.

Outbreaks of blastomycosis are typically associated with waterways.

The typical presentation of blastomycosis varies, and includes asymptomatic infection, acute or chronic pneumonia, and extrapulmonary disease

Symptoms of acute and chronic pulmonary involvement include productive cough, fever, chest pain, hemoptysis, and weight loss. Acute infection may be indistinguishable from viral or bacterial pneumonia.

Blastomycosis can involve every organ, although the lungs are most commonly affected. The most common extrapulmonary manifestation of blastomycosis is skin disease, with a characteristic finding of gray-violet verrucous lesions with irregular borders. Other skin findings may include ulcerative lesions or subcutaneous nodules.

Chest radiography of pulmonary blastomycosis typically shows non-specific findings of alveolar infiltrates with or without cavitation or mass lesions. Presumptive diagnosis can be made with visualization of the broadly-based budding yeast cells.Definitive diagnosis is with culture and growth from a tissue sample such as sputum or bronchial lavage.

In blastomycosis, the recommended treatment of mild-to-moderate pulmonary or extrapulmonary disease (excluding the CNS), is itraconazole for 6-12 months.

Patients with moderately severe or severe blastomycosis or disseminated infection including the CNS should be treated with amphotericin B.

Eosinophilic Pneumonia

In eosinophilic pneumonia, symptom onset is gradual. Patients generally present with asthma-like symptoms ongoing for several days. On physical examination, there are diffuse wheezes and fine inspiratory crackles suggestive of bronchial and interstitial involvement. Peripheral eosinophilia is also present.

Last updated