10 Dermatology

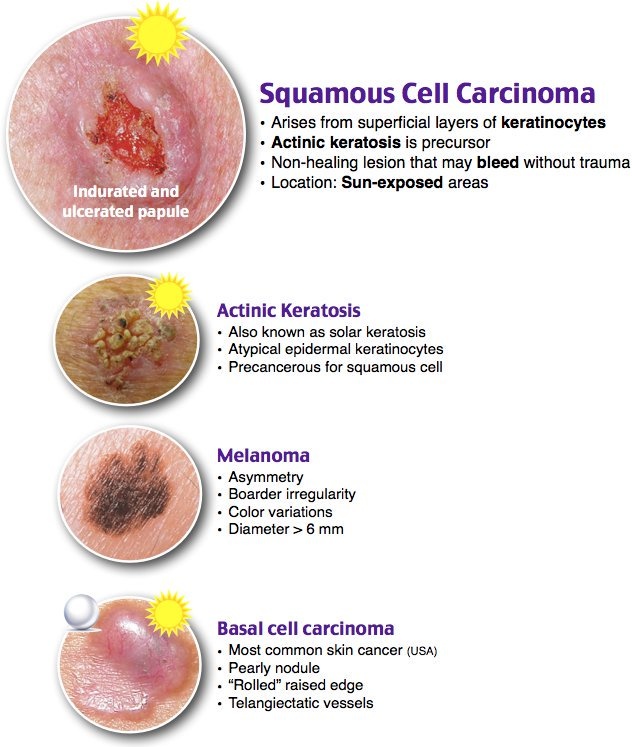

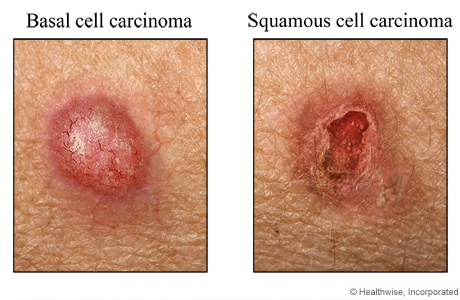

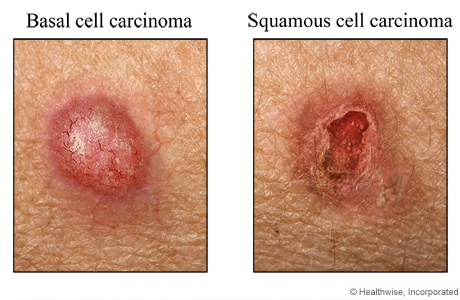

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin cancer in the United States. BCC typically occurs on sun-exposed areas and arises from mutated basal cells within the epidermal layer.

Predisposing factors thought to play a role in the development of BCC include:

Chronic sun exposure

Tanning beds

Genetic mutations (e.g. P53 gene)

Immunosuppression (e.g. HIV, organ transplantation)

Human papilloma virus infection

Regions near equator

Male gender

Fair skin

Basal cell carcinoma typically develops on sun exposed areas such as the face, scalp, ears, and hands. Basal cell carcinoma is more likely to develop on the upper lip, whereas squamous cell carcinoma is more likely to develop on the lower lip.

Characteristic features include lesions with a pearly, waxy appearance with telangiectases throughout the lesion.

Skin biopsy is the diagnostic modality of choice. Since BCC rarely metastasizes, laboratory and imaging studies are typically not required.

Complications associated with BCC include the following:

Metastasis (RARE)

Facial disfigurement

Scarring

Nerve damage

Treatment options for basal cell carcinoma consist of:

Electrodessication and curettage

Surgical excision

Cryotherapy

Topical medications

Radiation therapy

Topical creams, such as 5-Fluorouracil, imiquimod, and tazarotene, are used when patients cannot undergo surgery or radiation.

Radiation therapy is only used when disease is extensive or the patient cannot undergo surgery (e.g. allergic to anesthetics, taking anticoagulants, prone to keloid formation).

Mohs surgery is a specialized type of surgical excision where the tumor margins are optimally controlled, is used for tumors located in area with high cosmetic and/or functional concern.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common skin cancer in the United States. It results in scaly, ulcerated skin lesions.

Risk factors for the development of SCC include:

Chronic UV light exposure (e.g. sun tanning, tanning beds)

Immunosuppression (e.g. organ transplant, HIV)

Human Papilloma Virus infection

Marjolin's ulcer at site of an old burn or continuously draining sinus

Fair skin

Genetic mutations

Actinic keratosis

Female gender

venous ulcers, osteomyelitis, radiotherapy scars

marjolin's:

SCC can occur on any cutaneous area, but most commonly presents on sun exposed areas, with the head (i.e. lower lip, face, and scalp) and neck areas being most common.

The classic presentation is a lesion with a shallow ulceration and heaped up borders.

Even though visual examination may suggest SCC, only a skin biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

On physical examination SCC classically presents as crusting, scaling, ulcerated skin lesions.

SCC may result in complications such as:

Metastasis to distant sites

Facial disfigurement

Scarring

Nerve damage

Death

Treatment of SCC is dependent on the location and depth of the cancerous cells. Treatment options consist of:

Cryotherapy

Electrodessication and curettage

Surgical excision

Radiation therapy

Chemotherapy

Topical chemotherapy agents such as 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) and epidermal growth factor inhibitors are used as adjuvant therapy for high-risk types. Systemic chemotherapy is reserved for metastatic disease.

For SCC of the face and other cosmetically sensitive areas, Mohs surgery is the preferred treatment.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis and erysipelas are a cutaneous infection that develops due to bacteria penetrating broken skin.

Cellulitis is most commonly caused by S. aureus and group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (S. pyogenes).

Erysipelas is most commonly caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococci (S. pyogenes).

cellulitis:

erysipelas:

The cutaneous structures involved in cellulitis vs. erysipelas differ:

Cellulitis

Erysipelas

Deeper dermis & subcutaneous fat

Upper dermis & superficial lymphatics

Unlike in cellulitis, the lesions associated with erysipelas are raised relative to the surrounding skin, leaving a clear line of demarcation between the lesion and the surrounding skin.

Patients with erysipelas also tend to have a more acute onset of symptoms and systemic symptoms, such as fever and chills, are usually present. Cellulitis has a more indolent course.

Impaired lymphatic drainage from surgery can predispose to the development of cellulitis and erysipelas. Likewise, lymphatic damage sustained during the course of infection can increase the risk of local recurrence.

The typical presentation of a patient with cellulitis or erysipelas includes the following cutaneous findings:

Erythema

Edema

Warmth

The most common location of infection in both cellulitis and erysipelas are the lower extremities.

Severe infections that should be considered if there is rapid erythema with systemic toxicity include:

Necrotizing fasciitis

Toxic shock syndrome

Gas gangrene

Cellulitis and erysipelas are both clinical diagnoses based on clinical manifestations. Blood cultures and needle aspirations aren’t required for mild infections.

Cultures are more useful in cases where there is systemic toxicity.

Patients with either purulent or nonpurulent cellulitis can be treated empirically with oral antibiotics that include:

Clindamycin

Amoxicillin plus TMP-SMX

Amoxicillin plus tetracycline

Treatment of erysipelas in patients with systemic manifestations (e.g. fever, chills) is IV ceftriaxone or cefazolin.

Treatment of erysipelas in patients without systemic manifestations is oral penicillin or amoxicillin.

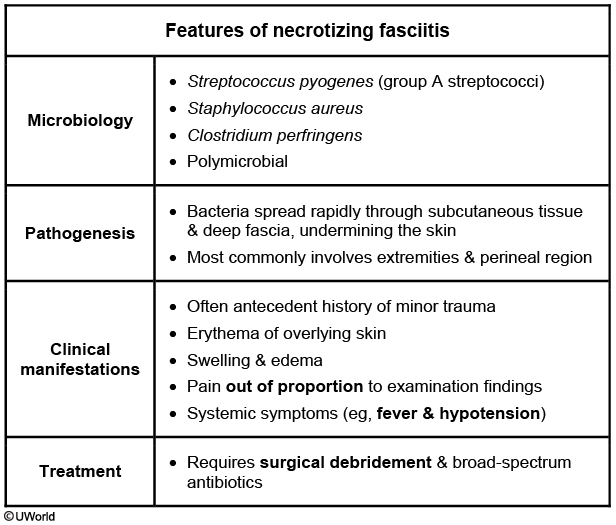

Necrotizing Fascitis

Deep-tissue infection (necrotizing fasciitis, clostridial gas gangrene) is also characterized by severe pain that is out of proportion to obvious clinical signs. These syndromes are commonly due to group A Streptococcus or mixed anaerobic infection. Symptoms generally evolve over several hours to days and are usually associated with skin necrosis, bullae, and crepitus or signs of significant systemic toxicity (high fever, hypotension). Abscess/cellulitis/hematoma does not have systemic signs. Pyomyositis is abscess of muscles and presents with systemic signs but the pain does not spread quickly to other places.

This patient has fever, hypotension, erythema, and swelling. Notably, she has pain out of proportion to the physical examination findings. In addition, her CT scan is suggestive of air in the deep tissue. This constellation of findings is concerning for necrotizing fasciitis. Necrotizing fasciitis is a rapidly spreading infection involving the subcutaneous fascia, generally following trauma. It can also result from significant peripheral vascular disease (ie, diabetes). Group A streptococci is the most frequently recovered pathogen, although necrotizing fasciitis is usually polymicrobial. Gas production by microbes leads to air in the soft tissues, which results in crepitus on examination in about 50% of cases.

Patients with necrotizing fasciitis have pain and swelling of the affected site. The pain is frequently more severe than expected based on the degree of swelling and erythema and usually precedes systemic signs such as fever or hypotension. Untreated necrotizing fasciitis progresses to rapid discoloration of the affected site, purulent discharge, bullae, and necrosis. Imaging can reveal the extent of the infection and identify air in the tissue bed. However, if necrotizing fasciitis is strongly suspected, therapy should not be delayed to pursue additional imaging. Broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and resection of necrotic tissue are necessary for treatment. Because of its rapid progression, necrotizing fasciitis causes significant morbidity and mortality even with aggressive treatment.

Decubitus Ulcers

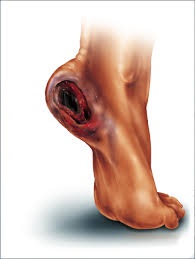

Decubitus ulcer (also known as a pressure ulcer) describes a localized ulceration, which typically develops over a bony prominence (e.g. sacrum, heel) from unrelieved pressure (i.e. hospital bed or wheelchair confinement).

Unrelieved pressure to the skin occludes local capillary networks, resulting in tissue ischemia, and ultimately tissue necrosis.

Immobility is the most important risk factor for decubiti. Patients confined to hospital beds or wheelchairs are at increased risk for decubitus formation, especially sacral decubiti.

Other risks include:

Nutritional deficiency

Urinary incontinence

Neurologic disorders (e.g. dementia, CVA)

Increased moisture (e.g. perspiration, feces)

Shearing forces (e.g. patients positioned at an incline).

Clinical presentation will vary depending on the stage (I – IV) and can range from mild erythema to extensive muscular necrosis.

Stage I represents intact skin with nonblanchable redness.

Stage II represents partial thickness loss of the epidermis and dermis with superficial ulceration.

Stage III represents full thickness loss of skin that extends into the subcutaneous fat tissue, but not into the muscle or fascia.

Stage IV represents full thickness loss of skin and subcutaneous tissue that extends into the muscle, tendons, and bone.

The best way to diagnose a decubitus ulcer is by determining its location, completing a thorough examination of the wound and tissue, and taking a tissue sample for wound cultures.

If there is bone involvement, a bone biopsy or MRI may be required to determine if the patient has osteomyelitis.

Decubitus ulcers may result in:

Permanent skin damage

Sinus tracts to the bowel and bladder

Sepsis

Osteomyelitis

Squamous cell carcinoma (Marjolin ulcer).

The first step in management focuses on patient positioning to help minimize tissue pressure and further damage. Patients should be repositioned every 2 hours regardless of the stage.

Optimizing caloric and nutritional status is extremely important in wound healing, as most patients are in a chronic catabolic state.

Stage I decubiti are treated by repositioning the patient.

Stage II decubiti are treated with occlusive dressings.

Stage III and IV decubiti require surgical debridement of the necrotic tissue and appropriate dressing changes. Some patients may benefit from hyperbaric and negative pressure therapy.

Melanoma

Melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer that arises from mutated melanocytes (pigment producing cells within the skin). Melanoma is predominantly a malignancy of the skin, but can occur anywhere in the body.

One of the most common causal relationships in developing melanoma is UV light exposure. Other risk factors include the following:

Fair skin

Tanning beds

Quantity of nevi on body

Immunosuppression (i.e. organ transplant)

White skin

The most common presenting symptom of melanoma is the development of a new mole or a change in color or size of an existing mole.

Other less common symptoms include:

Itching

Bleeding

Ulceration

The best initial step in diagnosing melanoma is a total body skin examination and use of the ABCDE mnemonic for nevi.

The ABCDE mneominc of melanoma includes:

Asymmetry

Border irregularity

Color variation

Diameter

Evolution of the lesion

On physical exam the entire body must be examined, especially the foot soles, fingernails, scalp, and rectum.

The gold standard for diagnosing melanoma is an excisional skin biopsy with a 1-2 mm rim of normal appearing skin.

Imaging studies such as CT, MRI, PET scan, and bone scan are used if metastasis are suspected.

Melanoma may result in the following complications:

Scarring

Keloid formation

Metastasis

Death

The most important prognostic factors in melanoma are tumor thickness and presence of ulceration.

The mainstay of melanoma treatment is surgical excision with negative margins. Adjuvant medications are used when distant sites are involved.

Mohs surgery is one of the best forms of excisional surgery types in treating melanoma. This form of surgery allows the surgeon to map the tissue removed and inspect the sample for tumor cells while the patient is still in the operating room. As a result, the surgeon is able to remove minimal tissue to achieve clear margins, with the option to remove more as required.

Skin Abscess

Skin abscesses are most often caused by S. aureus.

A carbuncle is a skin abscess that is a collection of boils, which are inflamed hair follicles containing pus.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is the term for recurrent abscesses in the axilla, groin, and perineum that result from chronic follicular occlusion and inflammation of apocrine glands. Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with metabolic disorders (e.g. diabetes, obesity).

Skin abscesses are generally:

Erythematous

Painful

Fluctuant

Cause localized skin swelling

The pain is frequently relieved when the abscess is drained.

If the specific pathogen causing a skin abscess needs to be identified, it must be cultured under sterile conditions. If not, the culture will likely pick up normal skin flora and/or be falsely positive.

Since the facial and ophthalmic veins are valveless, the spread of infection from a facial abscess can lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis.

The primary treatment for a large skin abscess is incision and drainage.

Last updated