22 Shock

Overview

Shock is a pathophysiologic state of systemic tissue hypoperfusion in which oxygen demand exceeds the supply capabilities of the circulatory system. It is a medical emergency.

The four broad categories of shock pathophsiology include:

Intrinsic cardiogenic shock

Obstructive cardiogenic shock

Hypovolemic shock

Distributive shock

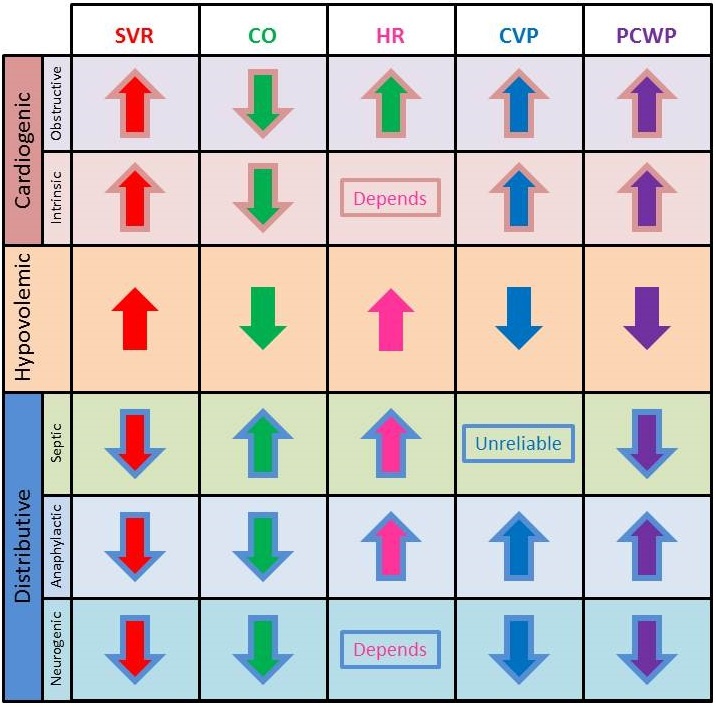

The type of shock can often be discerned if certain physiological parameters are known, as demonstrated in the accompanying table. This is a frequently tested concept.

Obstructive cardiogenic shock occurs when forces outside the heart significantly impede the normal flow of blood, resulting in extrinsic pump failure.

Intrinsic cardiogenic shock is the result of intrinsic pump failure.

Vasopressors and inotropes can be used in the treatment of patients with intrinsic cardiogenic shock to augment forward cardiac output.

Hypovolemic Shock

Hypovolemic shock is the result of inadequate blood or plasma volume causing decreased preload and insufficient cardiac output.

Hypovolemic shock can be divided into 2 broad pathophysiologic categories:

Hemorrhage: trauma, gastrointestinal bleeding, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, large hematomas (e.g. pelvic ring fractures, femur fractures), and ruptured aneurysms

Excess fluid loss: vomiting, increased insensible losses without sufficient repletion (e.g. fever), diarrhea, and large burns.

The left ventricle, decreased in size due to low filling volume, also compensates by increasing ejection fraction.

Treatment of hypovolemic shock includes:

IV fluids if due to a nonhemorrhagic cause

Transfusions if due to hemorrhagic cause after 3 L of fluids have been delivered

Surgery (if required) to stop ongoing blood loss

Specialized dressing if the cause is severe burns

Neurogenic Shock

Neurogenic shock is a type of distributive shock that occurs when sympathetic nervous system collapse results in widespread peripheral vasodilation and bradycardia (although tachycardia can sometimes occur).

Neurogenic shock is most commonly caused by central nervous system (CNS) or spinal cord injury.

In addition to hypotension and bradycardia, neurogenic shock presents with warm, well-perfused, hyperemic skin as a result of the peripheral vasodilation.

Treatment of neurogenic shock requires the use of IV fluids, vasoconstrictors to counteract the vasodilation, and atropine for bradycardia.

Septic Shock

Septic shock is a type of distributive shock that results from a systemic response to inflammatory cytokines.

Anaphylactic shock is a type of distributive shock that occurs in the setting of a generalized type I hypersensitivity reaction.

Intrinsic Cardiogenic Shock

Intrinsic cardiogenic shock occurs when the heart fails to generate sufficient cardiac output (CO) to adequately perfuse the tissues due to cardiomyopathies, arrhythmias, or mechanical abnormalities.

The most common cause of cardiogenic shock is acute cardiac dysfunction due to ventricular arrhythmia following myocardial infarction (MI). Other causes include:

Other hypoperfusing arrhythmias.

Cardiomyopathies: massive infarction involving > 40% of the left ventricular myocardium, decompensation of dilated cardiomyopathy, stunned myocardium secondary to prolonged ischemia, and myocarditis.

(Acute) mechanical abnormalities: acute valvular abnormalities (including papillary muscle rupture), acute septal disruption, and retrograde aortic dissection that distorts the aortic valve annulus. Note that in general, mechanical abnormalities that develop over time allow remodelling to occur such that intrinsic cardiogenic shock does not develop until an acutely decompensating stressor is present.

PE

Physical exam findings associated with cardiogenic shock include:

Jugular venous distention (JVD)

Crackles over the lung bases bilaterally in patients with pulmonary edema

Altered mentation

Cool, clammy skin

Weak, thready pulse

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of intrinsic cardiogenic shock is made with repeat electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrating recurrent ischemia and confirmed with echocardiogram demonstrating severe systolic dysfunction or mechanical abnormality.

Treatment

Treatment of intrinsic cardiogenic shock involves correction of the underlying disorder. For specific management protocols, please refer to:

Acute Coronary Syndrome: STEMI - Overview and Acute Management

Acute Coronary Syndrome: Unstable Angina & NSTEMI

Myocardial Infarction: Post-MI Complications and Long-term Management

Unlike some other forms of shock, IV fluids are contraindicated in the setting of intrinsic cardiogenic shock that is the result of acute left ventricular dysfunction because this can exacerbate the pulmonary edema; however, volume support is central to the management of intrinsic cardiogenic shock due to acute right heart failure in the setting of right ventricular infarction.

Vasopressors and inotropes can be use in the treatment of patients with cardiogenic shock:

The initial agent is generally a vasopressor such as dopamine or norepinephrine (for patients with marked hypotension).

Inotropic support with dobutamine is appropriate for less sick patients with low cardiac index and elevated PCWP who are not severely hypotensive.

Mechanical support devices such as an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) can rapidly stabilize a patient with intrinsic cardiogenic shock.

Obstructive Cardiogenic Shock

Obstructive cardiogenic shock is the result of extrinsic pump failure due to compression of the heart or massive obstruction to blood flow in the large vessels of the proximal arterial circulations that has the effect of reduced ventricular filling (insufficient preload) or impedance to ventricular emptying (insurmountable afterload).

Obstructive cardiogenic shock can develop in the following situations:

Massive proximal pumonary embolus (e.g. saddle embolus)

Tension pneumothorax

Severe pulmonary arterial hypertension

Cardiac tamponade

Severe constrictive pericarditis

Symptoms

Obstructive cardiogenic shock presents with the cardinal features of shock (hypotension, altered mentation, cool and clammy skin) along with features suggestive of an underlying condition:

Patients with a large pulmonary embolus may have signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea.

Patients with tension pneumothorax may present with tracheal deviation, unilaterally absent breath sounds, and signs of chest wall trauma.

Patients with cardiac tamponade may present with Beck’s triad and pulsus paradoxus.

Patients with constrictive pericarditis may present with a pericardial knock and Kussmaul’s sign.

Treatment

Conditions that cause obstructive cardiogenic shock can progress rapidly with high morbidity, so diagnosis is most appropriately made based on available history and rapid physical assessment, followed by immediate treatment of the underlying cause. Treatment of obstructive causes of shock should never be delayed for the purpose of further diagnostic workup

The best treatment for cardiogenic obstructive shock is to address the underlying cause of the obstructive physiology:

Massive pulmonary emboli require anticoagulation therapy

Tension pneumothorax requires chest tube placement

Severe pulmonary arterial hypertension requires inhaled iloprost or nitric oxide

Cardiac tamponade requires drainage of the pericardial space

Constrictive pericarditis requires surgical pericardectomy

SIRS

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is a clinical condition related to sepsis characterized by dysregulated inflammatory response to an infectious or noninfectious process. A patient must meet two or more of the following criteria to be diagnosed with SIRS:

HR: >90/min

Temperature: <36°C or >38°C

WBC count: <4000/mm3 or >12,000/mm3 or 10% bandemia

Respiratory rate: >20/min or PaCO2 < 32 mmHg

Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.

In a patient with sepsis, organ dysfunction can be defined as a change in the total Sequential (Sepsis-related) Organ Failure Assessment score (SOFA) (or quickSOFA [qSOFA]) of ≥2 points or more due to infection. The qSOFA criteria are:

Respiratory rate ≥22/min

Altered mentation

SBP ≤100 mmHg

Septic shock is a subset of sepsis in which the patient has hypotension refractory to fluid resuscitation. In addition to fulfilling the criteria for sepsis, patients both:

Require vasopressors to maintain MAP ≥65 mmHg

Have a serum lactate >2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL)

Note that these findings occur despite adequate fluid resuscitation.

Septic shock is caused by peripheral vasodilation leading to a severe drop in systemic vascular resistance. This is why patients with septic shock are described as having flushed, warm skin compared to patients with hypovolemic shock whose skin is cool due to peripheral vasoconstriction.

Risk factors for sepsis include:

Bacteremia

Advanced age

Diabetes

Cancer

Immunosuppression

In addition to having positive cultures, patients with sepsis often have other laboratory findings including

Elevated lactic acid

Increased BUN/creatinine ratio

Elevated liver enzymes

Leukocytosis or Leukopenia

Several physiologic parameters are used to compare septic shock to hypovolemic and cardiogenic shock:

Cardiac index: Increased

MVO2: Increased

Afterload: Decreased

PCWP: Normal or decreased

MVO2 = mixed venous oxygen saturation PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

Impaired cellular metabolism and dysregulation of the microcirculation (e.g. arteriovenous shunts that bypass capillaries) in septic shock lead to impaired oxygen extraction and delivery. This results in elevated mixed venous oxygen saturation (MVO2) and increased blood lactate despite the presence of an increased cardiac index and circulatory volume.

Obtaining blood, sputum or urine samples for culture and gram staining are important to diagnosis sepsis and to administer appropriate antibiotic therapy. It is critical that samples are taken BEFORE administration of empiric antibiotic therapy, to avoid interfering with culture growth and giving a false negative result.

Two thirds of sepsis cases in the U.S. are caused by gram positive bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly isolated gram positive pathogen.

One quarter of sepsis cases are caused by gram negative bacteria. E. coli is the most commonly isolated gram negative pathogen in cases of sepsis where gram negative bacteria are the causative pathogen.

One tenth of sepsis cases are caused by fungal infections. Candida albicans is the most commonly isolated fungus in cases of sepsis where fungus is causative pathogen.

Patients who acquire sepsis in a hospital setting must be empirically treated with antibiotics to cover 3 most common nosocomial infections including:

MRSA

Pseudomonas

E. coli

Early and aggressive treatment of sepsis and septic shock includes the use of:

Broad spectrum antibiotics

IV fluids

Pressors

Norepinephrine is a first-line vasopressor in the management of septic shock. Vasopressors are generally reserved for patients who remain hypotensive even after administration of IV fluids.

Patients who present with symptoms of sepsis should be immediately started on high doses of empiric antibiotic therapy until the specific pathogen is identified via culture, at which point they may be transitioned to targeted antibiotic therapy. It is critical that these patients be treated aggressively if there is any clinical suspicion of infection.

Tamponade

Cardiac tamponade occurs when fluid accumulates under high pressure in the pericardial space, compressing the heart's chambers and elevating the filling pressure. In other words, the diastolic filling pressure in each chamber becomes equal to the pressure in the pericardial space.

The most common etiologies of cardiac tamponade are those causing acute pericarditis:

Post-viral

Uremia

Neoplastic

You can remember the most common etiologies of acute pericarditis (and thus tamponade) by the mnemonic PUN (Post-viral, Uremic, Neoplastic).

Acute hemopericardium can also cause tamponade physiology. This generally results from one of the three following conditions:

Blunt or penetrating chest trauma

Rupture of the free wall of the left ventricle following myocardial infarction

Complication of a retrograde aortic dissection

Symptoms

Because the right and left atria cannot accommodate systemic and pulmonary return, respectively, blood may back up leading to acute signs of right-sided failure (e.g, hypotension, jugular venous distention) and left-sided failure (e.g. dyspnea, tachypnea).

Cardiac tamponade results in a decrease in preload, decrease in systolic stroke volume, and diminished cardiac output.

Key physical findings include jugular venous distention (JVD), muffled heart sounds, and systemic hypotension--the classic syndrome known as Beck's triad. Additionally, physical examination may reveal pulsus paradoxus. Note that Kussmaul sign (jugular venous distention with inspiration) is associated with constrictive pericarditis, NOT cardiac tamponade. Kussmaul sign, unlike pulsus paradoxus, IS physiologically paradoxical.

Pulsus paradoxus refers to a drop of 10 or more mm Hg in systolic pressure with inspiration. Note that this is not actually physiologically paradoxical, but rather an exaggeration of normal physiology.

Manifestations of cardiac tamponade on echocardiography include:

Diastolic collapse of the right atrium and ventricle

Since the right side of the heart is under lower pressures, it is most susceptible to compression by pericardial effusion

Bulging of the interventricular septum into the left ventricle

Due to constriction of right ventricle and underfilling of the left ventricle; accentuated by inspiration

However, under no circumstances should the definitive treatment of clinically evident or suspected hemodynamically significant tamponade be delayed for the purpose of confirming the diagnosis.

The definitive diagnosis of cardiac tamponade is made with cardiac catheterization, generally in the setting of catheter pericardiocentesis, which both confirms the diagnosis and allows for the definitive treatment.

Compression of the right ventricle in cardiac tamponade slows the emptying of the right atrium, resulting in a blunting of the y descent on right atrial or jugular venous pressure tracings.

Immediate removal of the high-pressure fluid surrounding the heart is the only definitive therapy for cardiac tamponade. This is accomplished by either catheter pericardiocentesis (i.e. echocardiographically-guided percutaneous drainage) or surgical drainage (i.e. cardiac window). Drainage via catheter pericardiocentesis is the preferred method, as it is associated with lower rate of complications and mortality. However, a surgical approach is prefered in the setting of traumatic hemopericardium, purulent pericarditis, and recurrent malignant pericardial effusions.

Hemodynamic compromise in the setting of a high clinical suspicion for cardiac tamponade is an indication for emergent pericardiocentesis without further diagnostic workup.

The use of positive pressure ventilation in patients with cardiac tamponade should be avoided since the increased intrathoracic pressure can decrease venous return (preload), thereby further reducing cardiac output.

This can result in life-threatening hypotension.

Untreated, acute cardiac tamponade can rapidly progress to extra-cardiac obstructive shock with insufficient forward cardiac output to supply the systemic demands.

Last updated