12 ENT

ENT Cancers

Risks

Head and neck cancers are becoming more common in younger patients. Risk factors for its development include:

Smoking tobacco products (including second hand smoking)

Alcohol (may be synergistic with tobacco)

Epstein-Barr Virus (nasopharyngeal carcinoma or lymphoma) (China, Africa, Middle East)

Human Papillomavirus (type 16)

HIV (predisposes to lymphoma)

Occupational exposures (e.g. formaldehyde, hydrocarbons)

Prior radiation therapy

Plummer Vinson syndrome

The most common histological type of head and neck cancers in adults is squamous cell carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinoma is predominately secondary to alcohol, smoking, and HPV infections.

The most common type of head and neck cancer in children is lymphoma.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is becoming an increasingly recognized cause of squamous cell head and neck cancer in young, non-smokers. This is thought to be transmitted sexually.

Symptoms

Oral cavity cancers typically present with symptoms of:

Oral pain

Non-healing ulcers

Difficulty swallowing

Weight loss

Ear pain (referred pain)

Dysarthria

Pharyngeal cancers typically present with symptoms of:

Throat pain

Bleeding

Difficulty sleeping secondary to breathing difficulties

Trouble swallowing

Referred ear pain

May be asymptomatic

Laryngeal cancers typically present with symptoms of:

Hoarseness

Trouble swallowing

Coughing

Hemoptysis

Human papillomavirus (HPV) induced cancers may present initially as a cystic mass, in which fine needle aspiration would not be effective.

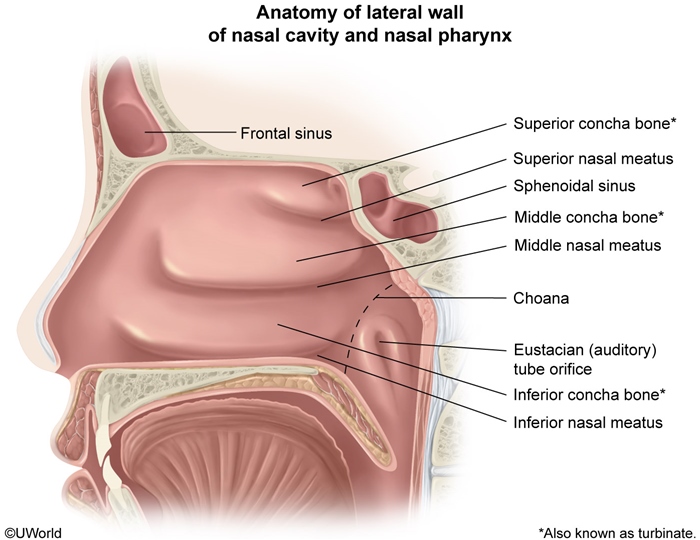

Nasopharyngeal carcionoma (NPC) tumors obstruct the nasopharynx and invade adjacent tissues, often resulting in nasal congestion with epistaxis, headache, cranial nerve palsies (eg, facial numbness), and/or serous otitis media (eustachian tube obstruction). Early metastatic spread to the cervical lymph nodes may cause a nontender neck mass (as in this patient).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a head and neck cancer relies upon a history and a physical exam which includes direct laryngoscopy for visualization of any masses.

Head and neck cancers may present with a single, painless, enlarged jugular lymph node.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) induced cancers may present initially as a cystic mass, in which fine needle aspiration would not be effective.

Imaging studies such as CT, MRI, and PET scan are used to stage malignancies. This should be done prior to biopsy to prevent false readings on PET imaging.

Fine needle aspiration of an enlarged lymph node has a high diagnostic probability. Sentinel lymph node biopsies may be used for both staging and diagnosis.

Open biopsy should never been done as it could alter staging and surgical management of the tumor.

Treatment

Head and neck cancers are typically treated depending on the extent of malignancy involvement:

Localized tumors are treated by radiation or resection (resection for oral cavity tumors)

Advanced malignancies are treated with a combination of resection, radiation, and chemotherapy (resection for oral cavity tumors)

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas are preferentially treated with radiation therapy.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) related head and neck cancers may be prevented with the tetravalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil).

ENT Infections

Ludwig

A form of cellulitis located in the submandibular space bilaterally and is typically secondary to a dental infection.,

Patients with Ludwig's angina symptomatically present with:

Pain

Drooling

Dysphagia

Fevers

Chills

Difficulty breathing in advanced disease

On physical examination, Ludwig's angina typically presents with:

An erythematous and raised floor of the mouth

Cyanosis (present in advanced stages)

Leaning forward (helps maintain a patent airway)

Ludwig's angina is diagnosed by both physical exam and CT imaging.

The initial therapy for Ludwig's angina is supportive therapy, however advanced cases require:

Airway protection via nasal intubation (tracheostomy if emergent)

Antibiotics such as ampicillin-sulbactam (Unasyn)

If left untreated, Ludwig's angina may cause airway obstruction and asphyxiation.

Epiglottitis

Epiglottitis is the inflammation of the epiglottis commonly caused by:

Haemophilus influenzae type b, although the rates are declining due to vaccinations

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae species

Staphylococcus aureus

Streptococcus species

Trauma (e.g. foreign body irritation)

Patients with epiglottitis typically present with acutely developing symptoms of:

Dysphagia

Drooling

Anxiety

No cough (versus croup)

Fever

Muffled voice

Dyspnea (lessened by leaning forward)

Stridor

The diagnosis of epiglottitis depends on visualization of an inflamed epiglottis and lateral neck radiographs which classically demonstrate the thumb print sign.

The management of epiglottitis involves:

Airway management

Antibiotic regimens such as ceftriaxone (Rocephin) and vancomycin (Vancocin)

If left untreated, patients with epiglottitis may develop:

Airway compromise

Abscess formation

Mastoiditis

Mastoiditis, the inflammation of the mastoid air cells, is usually caused by direct extension of an acute otitis media.

Mastoiditis is typically caused by:

Streptococcus pneumoniae

Streptococcus pyogenes

Staphylococcus aureus

Patients with mastoiditis typically present with:

Overlying acute otitis media

Fever

Postauricular pain

Postauricular mass

Displacement of the ear inferiorly

May be asymptomatic

Mastoiditis is diagnosed by history and physical exam, with CT scan used to confirm the diagnosis.

Mastoiditis is managed depending on its severity:

If no involvement of adjacent structures, use intravenous antibiotics such as vancomycin (Vancocin) and myringotomy

If adjacent structures are involved, use intravenous antibiotics such as vancomycin, myringotomy, and mastoidectomy

If left untreated, patients with mastoiditis may develop:

Facial nerve palsy

Hearing loss

Vertigo

Intracerebral lesions

Epidural abscesses

Rhinoplasty

Complications are common following rhinoplasty, and up to one in four rhinoplasties may need revision. Common complications include patient dissatisfaction, nasal obstruction and epistaxis. Those that involve the nasal septum are less common but more serious. The septum is made up of cartilage and has poor blood supply contrasting sharply with the rich anastomosing blood supply of the nasal sidewall. The underlying cartilage relies completely on the overlying mucosa for nourishment by diffusion. Because of the poor regenerating capacity of the septal cartilage, trauma or surgery on the septum may result in septal perforation. The typical postoperative presentation is a whistling noise heard during respiration. Following nasal surgery, septal perforation is typically the result of a septal hematoma though a septal abscess may also be the cause. Additional conditions that can cause septal perforation are self-inflicted trauma (nose picking), syphilis, tuberculosis, intranasal cocaine use, sarcoidosis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's).

Otitis Externa

Otitis externa is the inflammation of the external auditory canal. Risk factors for otitis externa include:

Trauma

Cerumen removal with a cotton swab (causing microperforations)

Swimming or water exposure in general (changes external auditory canal flora to gram negative predominantly)

Foreign bodies (e.g. headphones)

The most common microbiological causes of otitis externa are:

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (associated with water exposure)

Staphylococcus epidermidis

Staphylococcus aureus

Patients with otitis externa typically present with the following symptoms:

Localized ear pain

Pruritus

Fluid discharge

Changes in hearing

The diagnosis of otitis externa is typically made through history and physical exam, which must include otoscopy.

On physical exam, patients with otitis externa typically have:

A tender auricle or tragus when palpated

White discharge may be present

Erythematous external auditory canal on otoscopy

Mobile tympanic membrane on pneumatic insufflation (versus otitis media)

No granulation tissue or mastoid tenderness (versus malignant otitis externa)

Patients with otitis externa are typically managed through:

Cleaning of the ear canal using otoscopy and a cotton swab

Otic antibiotic drops such as ofloxacin (Floxin), ciprofloxacin (Cipro), polymyxin B, neomycin, or tobramycin (Tobrex)

Topical hydrocortisone to reduce swelling

Acetic acid drops (a low pH limits bacterial growth)

If left untreated, patients with otitis externa may develop:

Malignant otitis externa

Abscess formation

Tympanic membrane perforation

Otomycosis (fungal infection following an antibiotic regimen)

Malignant OTE

Malignant (or necrotizing) otitis externa is an infection of the external auditory canal and the surrounding bony skull.

Malignant otitis externa typically occurs in elderly diabetic patients.

Malignant otitis externa is most commonly caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Patients with malignant otitis externa typically present with:

Severe ear pain (out of proportion to simple otitis externa)

Drainage from the ear

Granulation tissue visible with otoscopy

Advanced cases may have cranial nerve involvement

The diagnosis of malignant otitis externa is dependent upon:

History and physical exam

CT imaging showing bony erosions

Biopsy to distinguish from squamous cell carcinoma

Bacterial culture for Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Intravenous ciprofloxacin is the the antibiotic of choice for the treatment of malignant otitis externa.

Otitis Media

Otitis media refers to an infection of the middle ear.

The most common causes of otitis media include:

S. pneumoniae

H. influenzae

M. catarrhalis

S. pyogenes

Viruses

Children are more at risk for developing otitis media than adults due to:

A shorter and more horizontal eustachian tube

Pacifier use

Hypertrophic tonsillar tissue

Symptoms and signs of otitis media include:

Ear pain and decreased hearing

Fever

An inflamed tympanic membrane with decreased mobility and poor light reflex

Otitis media with effusion (OME) refers to the presence of middle ear fluid in the absence of extensive inflammation, localized pain, and systemic signs (e.g. fever, malaise).

Patients with HIV have an increased risk of developing otitis media with effusion (OME) due to regional lymphoid tumors. Thus, the presence of lymphomas should be excluded in patients with HIV that present with OME.

Despite the absence of signs of inflammation, pain and systemic signs, patients with otitis media with effusion may present with a conductive hearing loss.

Otitis media with effusion can be distinguished from acute otitis media by the presence of a retracted tympanic membrane in otitis media with effusion.

Pneumatic otoscopy is the standard examination technique for diagnosing otitis media.

Complications of acute otitis media occur primarily due to local spread of the infection and include:

Mastoiditis

Meningitis

Hearing loss

Sigmoid sinus thrombosis

Brain abscess

The preferred initial treatment for acute otitis media in adults is amoxicillin.

Resistant cases may require amoxicillin and clavulanic acid or a stronger cephalosporin.

Surgical placement of tympanostomy tubes into the tympanic membrane is indicated in recurrent cases to help promote drainage of the middle ear.

Complications of chronic or recurrent otitis media include:

Extracranial and intracranial spread of infection

Facial paralysis

Cholesteatoma

Peritonsillar Abscesses

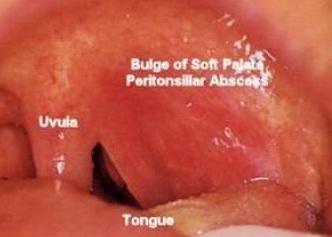

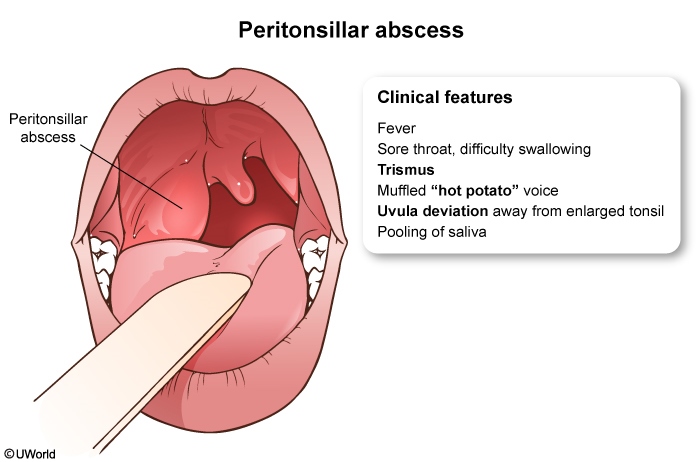

Peritonsillar abscesses are loculations of purulence located between the palatine tonsillar capsule and the pharyngeal muscles.

This patient has fever, pharyngeal pain, and earache suggesting a possible peritonsillar abscess (PTA). PTA, also known as quinsy, is an acute bacterial infection of the region between the tonsil and the pharyngeal muscles. It begins as persistent tonsillitis/pharyngitis and progresses to cellulitis/phlegmon, with pus collecting into an abscess within a week of symptom onset. PTA is most common in older adolescents and young adults, and drug or alcohol use increases the risk.

Peritonsillar abscesses are typically polymicrobial, including:

Streptococcus pyogenes

Staphylococcus aureus

Anaerobes (e.g. Fusobacterium spp.)

On physical exam, patients with a peritonsillar abscess are toxic-appearing and have concerning symptoms of trismus (inability to fully open mouth, spasm of jaw), muffled voice, odynophagia and respiratory distress.

Differential diagnoses that may resemble peritonsillar abscess include other deep tissue infections of the head and neck (e.g. retropharyngeal abscess) and epiglottitis. The presence of uvular deviation and unilateral cervical lymphadenopathy are relatively unique to peritonsillar abscess and can aid in diagnosis.

A CT scan with IV contrast is the imaging modality of choice for confirming the diagnosis of a peritonsillar abscess and also to see the extent of spread.

Two key components of the management of patients with peritonsillar abscess are:

Abscess drainage (via needle aspiration or incision and drainage)

Antibiotics

Supportive care (e.g. hydration, analgesia) should also be provided.

Initial empiric antibiotics used to treat peritonsillar abscess include parenteral. Use for GAS and oral anaerobes:

Ampicillin-sulbactam (Unasyn)

Clindamycin

Vancomycin or linezolid can be added to either of these agents in patients who do not respond to treatment or those with severe disease.

If left untreated, a peritonsillar abscess may cause:

Respiratory obstruction

Septic shock

Necrotizing fasciitis

Vascular compromise (internal jugular vein thrombosis)

Salivary Gland Tumors

Salivary gland tumors are rare, representing 6 - 8% of all head and neck tumors in the United States.

Risk factors for salivary gland tumors include:

Radiation

Viral infections (HIV, EBV)

Smoking (Warthin’s tumors)

Industrial exposures

Salivary gland tumors in order of prevalence:

Pleomorphic adenoma (60%)

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma (8%)

Warthin’s tumor (7%)

The most common benign tumor of the salivary glands is the pleomorphic adenoma (aka mixed tumor).

The most common salivary gland malignancy is the mucoepidermoid tumor, which typically arises in the parotid glands and involves the facial nerve. (Malignant = Mucoepidermoid)

Warthin’s tumors are benign cystic tumors most commonly in the parotid glands.

Symptoms

Patients with salivary gland tumors typically present with:

Painless swelling or mass in the face and neck

Facial muscle paralysis from parotid gland invasion of the facial nerve

Swollen lymph nodes in the neck

Diagnosing salivary gland tumors requires either a fine needle aspiration (FNA) or a ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy to determine whether the tumor is benign or malignant.

Staging requires a CT or MRI.

The treatment of salivary gland tumors generally involves surgery such as a parotidectomy.

Complications of parotidectomy include:

Facial paralysis from facial nerve irritation or transection

Frey syndrome (sweating over parotid area while chewing)

Retropharyngeal Abscess

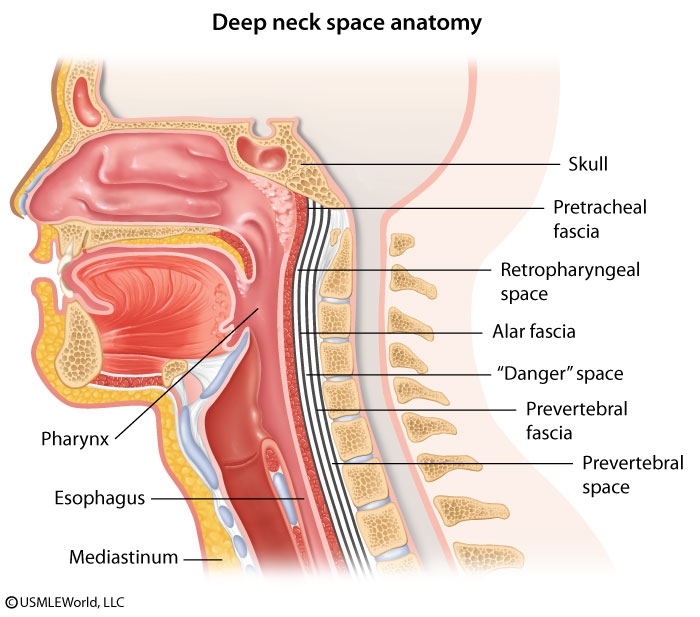

The retropharyngeal space is a deep compartment of the neck defined anteriorly by the buccopharyngeal fascia and constrictor muscles of the pharynx and posteriorly by the alar fascia. It communicates laterally with the parapharyngeal space. This patient has a retropharyngeal abscess with neck pain, odynophagia, and fever following penetrating trauma to the posterior pharynx. Examination findings can include nuchal rigidity and bulging of the pharyngeal wall. Although deep space infections of the neck have become less common since the advent of widespread antibiotic use, they can progress rapidly with potentially fatal complications.

Infection within the retropharyngeal space drains inferiorly to the superior mediastinum. Spread to the carotid sheath can cause thrombosis of the internal jugular vein and deficits in cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII. Extension through the alar fascia into the "danger space" (between the alar and prevertebral fasciae) can rapidly transmit infection into the posterior mediastinum to the level of the diaphragm. Acute necrotizing mediastinitis is a life-threatening complication characterized by fever, chest pain, dyspnea, and odynophagia, and requires urgent surgical intervention.

Last updated