24 Urology

Acute Urinary Retention

Acute urinary retention, the inability to pass urine, is the most common urologic emergency, typically occurring in men over the age of 60 with benign prostatic hyperplasia.

Risk factors for acute urinary retention include:

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (prostatic volume greater than 30 mL)

Advanced age

Use of anticholinergic or sympathomimetic medications

Over-distention of the bladder

Spinal cord injuries or other neurological disorder

Tumors (e.g. fibroids in women)

Patients with acute urinary retention typically present with:

Inability to urinate

Lower abdominal pain or discomfort

Fullness on suprapubic palpation

The management of acute urinary retention includes:

Immediate bladder catheterization for decompression (may require suprapubic catheterization if the obstruction is severe)

BPH drugs in men (e.g. tamsulosin, finasteride)

Surgery (e.g. transurethral resection of the prostate)

BPH

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a disease of middle-aged and older men, with the prevalence increasing with increasing age (19-46% over the age of 50).

BPH develops in the periurethral zone (transitional zone) of the prostate leading to the obstructive symptoms seen in patients with BPH.

BPH DOES NOT predispose patients to prostate cancer.

The clinical presentation of BPH is related to the obstructed urine flow and includes:

Hesitancy

Weak urine stream

Frequency

Urgency

Dysuria

Nocturia

The diagnostic workup of BPH begins with a history and physical. A DRE (digital rectal exam) will reveal a uniformly enlarged, rubbery prostate. Contrast with prostate cancer, in which the prostate is non-uniformly enlarged with lumps and bumps.

There may be a mild increase in prostate specific antigen (PSA), which is age-dependent. For instance, the normal serum PSA for men 40 to 49 years old is 0-2.5 ng/mL, and for men 70 to 79 years old; 0-6.5 ng/mL. In addition the race of the patient should be considered when evaluating a serum PSA level.

The American Urological Association (AUA) recommends two laboratory studies to evaluate patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with BPH:

Urinalysis to look for infection or blood (associated with bladder cancer or renal calculi)

Serum PSA to screen for prostate cancer

There are several complications of untreated BPH from urinary obstruction:

Bilateral hydronephrosis

Bladder diverticula and smooth muscle hypertrophy

Predisposition to infection due to urine stasis

Prostatic infarct: painful, enlarged, firm gland with increased PSA

Behavior modifications are advised, which includes avoiding liquids before going out or going to bed, reduced caffeine and alcohol, and double voiding to completely empty bladder. Mild to moderate symptoms are initially treated with an alpha-blocker (e.g. tamsulosin, terazosin), which provide immediate benefits. Combination of an alpha-blocker and a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor (e.g. finasteride) is suggested for patients with severe symptoms, large prostates, and/or failed response to an alpha-blocker.

If refractory to medication, BPH is treated with TURP (transurethral resection of the prostate).

If refractory to medication but the patient is not a good surgical candidate, the BPH is treated with transurethral needle ablation.

Congenital Defects

Low implantation

Low implantation of the ureter is usually asymptomatic in boys but leads to unusual urinary symptoms in girls. Urine is deposited into the bladder by the normal ureter that allows appropriate voiding intervals. However, the low implanted ureter leads to urine that drips into the vagina, causing constant urinary leakage in females.

Imaging tests used to diagnose low implantation of the ureter include:

Renal ultrasound (initial diagnostic test)

MRI or CT with contrast

Voiding cystourethrogram

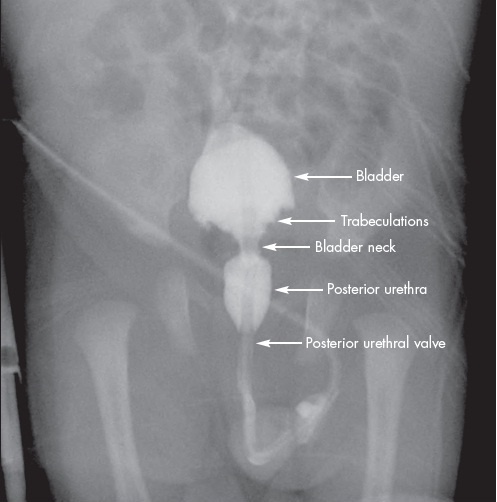

Posterior Urethral Valves

Posterior urethra valves is the most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction in male newborns resulting from an obstructing membrane in the posterior urethra from abnormal in utero development.

Posterior urethra valves is diagnosed with voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), which is characterized by an abrupt tapering of urethral caliber. It is associated with vesicoureteral reflux in 50% of children. Diagnosis can also be made by cystoscopy by direct visualization.

The treatment for posterior urethra valves is surgical endoscopic valve ablation. In select cases, fetal surgery is necessary for those with severe oligohydramnios, in an attempt to limit the associated lung underdevelopment that is seen at birth.

Reflux

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is an abnormal retrograde movement of urine from the bladder into the ureters. Children with VUR are predisposed to UTIs that can present as lethargy and failure to thrive in newborns, while infants and young children typically present with the following symptoms:

Dysuria

Increased urinary frequency and urgency

Malodorous urine

Low abdominal pain

Low-grade fevers

There should be a high degree of suspicion for VUR when a child <2 years old is diagnosed with a febrile UTI. A first-time febrile UTI in a child (boy or girl) younger than 2 years of age warrants a renal and bladder ultrasound.

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is diagnosed with voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) showing retrograde urine flow. Two indications for getting a VCUG to diagnose VUR are:

Recurrent febrile UTIs in a child < 2 years of age

A positive renal ultrasound upon first febrile UTI < 2 years of age

Treatment of VUR is low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis (often TMP-SMX) until resolution of VUR occurs, as most cases will resolve spontaneously. Surgical treatment is only necessary in very severe cases that show pyelonephritic changes or renal deterioration.

Ureteropelvic junction obstruction

Ureteropelvic junction obstruction is most commonly caused by intrinsic stenosis obstructing the flow of urine from the renal pelvis to the proximal ureter. The obstruction is usually not symptomatic until a large diuresis (for example, a first big drinking episode). Colicky flank pain is the most common clinical manifestation.

The work up for ureteropelvic junction obstruction consists of the following imaging studies:

Renal ultrasonography showing hydronephrosis

Voiding cystourethrogram to rule out vesicoureteral reflux

Diuretic renogram showing delayed clearance at the ureteropelvic junction

Most children are treated conservatively and monitored closely. Surgical intervention is indicated in the event of significantly impaired renal drainage.

Hypospadius

Hypospadias, which is more common than epispadias, is caused by failure of urethral folds to fuse completely and is characterized by the external urethral orifice opening on ventral surface of the penis.

The treatment for hypospadias is corrective surgery in order to prevent urinary tract infections. Children with hypospadias should never be circumcised since the skin of the prepuce is needed during surgical correction.

Epispadias is caused by faulty positioning of the genital tubercle during development and is characterized by the external urethral orifice opening on the dorsal surface of the penis.

Epispadias is associated with exstrophy of the bladder.

Epididymitis

Epididymitis is inflammation of the epididymis, caused by testicular inflammation (orchitis).

Etiologies of epididymitis include:

Chlamydia trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae (young, sexually active men)

Gram-negative aerobic rods (older men, > 35 years of age)

Local trauma

The classic symptom of epididymitis is unilateral testicular pain and tenderness that is relieved by supporting the scrotum, which relieves tension on the spermatic cord and the epididymis. Other symptoms include dysuria and induration.

Part of the differential diagnosis of the acutely painful scrotum is testicular torsion. Patients with suspected epididymitis should undergo testicular ultrasound to rule out testicular torsion.

(Note, however, that cases of suspected torsion are urological emergencies and should not be delayed by ultrasound confirmation).

Urinalysis in cases of epididymitis will show WBCs, whereas urine studies in testicular torsion almost always lack pyuria.

If caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and/or N. gonorrhoeae, epididymitis is treated with ceftriaxone/doxycycline or ceftriaxone/fluoroquinolones.

If non-infectious, NSAIDs and scrotal support are the preferred treatment.

Hydroceles

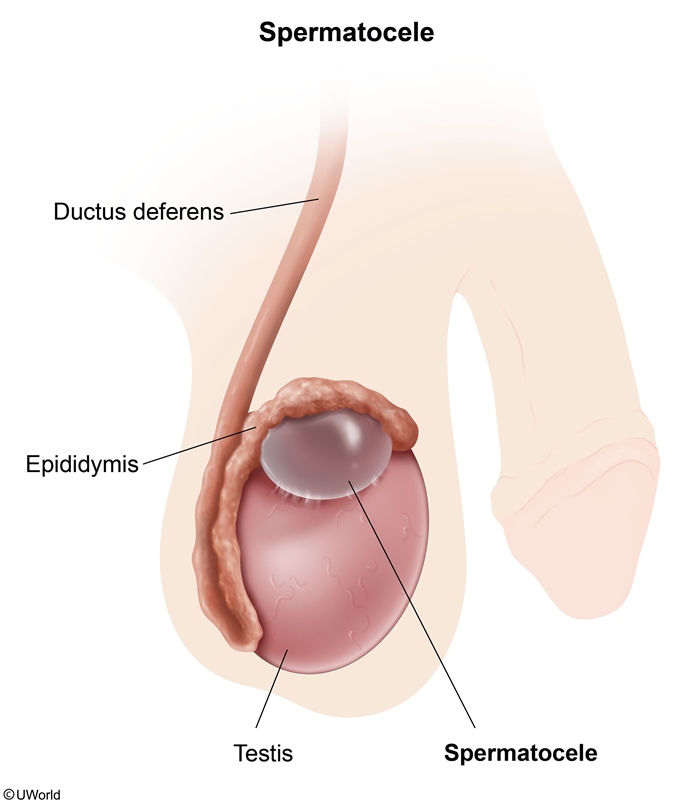

Spermatocele

A spermatocele is a cystic structure containing sperm, located within the epididymis.

A spermatocele presents as a painless scrotal swelling which does not cause symptoms or infertility.

On physical exam, a spermatocele may present as:

A palpable mass

Separate from the testis on palpation

Transilluminates (versus testicular tumors which do not)

Spermatocele and testicular cancer do not change in size with valsalva or position

When in doubt about testicular cancers, an ultrasound is useful in confirming the diagnosis of a spermatocele.

Spermatoceles are managed supportively, but surgically excised if symptomatic.

Varicocele

A varicocele is a dilation of the pampiniform plexus of veins that surrounds the spermatic cord.

Varicoceles classically occur following blockage of the left spermatic vein as it enters the left renal vein, but may occur in any instance that increases venous pressure.

The left spermatic (gonadal) vein drains to the left renal vein, which then passes between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the aorta. The left renal vein is vulnerable to compression beneath the SMA ("nutcracker effect"), leading to increased pressure in the spermatic vein, incompetence of the valves, retrograde blood flow, and venous dilation. In contrast, the right spermatic vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava; right-sided varicoceles are relatively rare and can be a sign of malignant compression (eg, renal cell carcinoma) or thrombosis.

Patients with a varicocele may be asymptomatic or present with:

Scrotal swelling

Aching scrotal pain

Sense of fullness in the scrotum

Testicular atrophy

Symptoms are typically exacerbated by standing and relieved by lying down due to the pooling of venous blood.

On physical exam, a varicocele typically:

Feels like a “bag of worms” due to dilation of the pampiniform plexus

Increases in size with increased intra-abdominal pressure (e.g. Valsalva, standing)

Decreases in size while the patient is supine

Does not transilluminate

US: retrograde venous flow

Varicoceles are usually managed supportively. Surgery is considered if one of the following criteria are met:

Decreased sperm count

Bilateral varicoceles

Pain

Surgery is via gonadal vein ligation.

Untreated varicoceles can lead to infertility because of testicular atrophy and hypogonadism secondary to increased scrotal temperature.

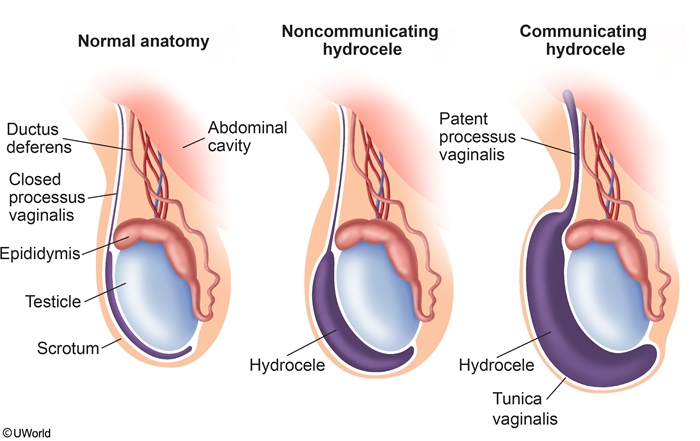

Hydrocele

A hydrocele is a collection of peritoneal fluid between the visceral and parietal layers of the tunica vaginalis within the scrotum.

Hydroceles come in two variants:

Communicating hydroceles develop from a closure defect of the processus vaginalis, allowing peritoneal fluid to enter the cavity.

Noncommunicating hydroceles develop from local secretion of fluids.

Patients with a hydrocele generally present with symptoms of:

Painless scrotal swelling

Fullness of the scrotum

Worsening of symptoms throughout the day (due to peritoneal connection)

Hydroceles are diagnosed based on palpation, transillumination,and ultrasound.

On physical exam, patients with a hydrocele typically have a scrotal swelling that:

Transilluminates (both communicating and noncommunicating)

Increases in size with standing or Valsalva (if communicating)

Does not reduce or change in size (if noncommunicating)

Hydroceles are typically managed supportively. Surgery is done if the hydrocele is symptomatic or persists for greater than one year.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer (adenocarcinoma) is the most common nondermatologic malignancy in males at rate of 128.3 per 100,000 (2011).

In males, lung and prostate cancer are the first and second, respectively, most common causes of cancer-related deaths.

Prostate cancer typically arises in the peripheral zones of the prostate.

Risk factors for prostate cancer include:

Advanced age*

Prostatitis

Family history of prostate cancer

High-fat diet

*Age is the most important risk factor. There is a strong relationship between age and rates of prostate cancer: 31-40 years, 9 to 31%; 81-90 years, 40 to 73%.

Since prostate cancer begins in the peripheral zones of the prostate, it is normally asymptomatic until advanced.

Once symptomatic, urinary symptoms of prostate cancer are related to the obstruction of urine flow:

Urinary retention

Weak urine flow

Frequency

Hesitancy

The main site of prostate cancer metastasis is bone, in particular the vertebrae. The clinical manifestations include pain (most common) and pathologic fractures.

The treatment of prostate cancer depends on the stage.

Management

If the cancer has not yet spread, it can be sucessfully treated with external beam radiation or brachytherapy (radioactive seed implants).

More extensive tumors can be treated with a radical prostatectomy, through varying approaches:

Retropubic

Perineal

Laparoscopic

Robotic

The following are used in treating metastatic prostate cancer:

GnRH agonist (e.g. leuprolide)

Androgen receptor antagonist (e.g. flutamide, bicalutamide)

Chemotherapy (not very effective)

Since many prostate cancers are very slow growing, older men are often observed because they are more likely to die from something unrelated to their prostate cancer.

Once treated, PSA is regularly measured to monitor for metastases and recurrence.

Screening

Current guidelines conflict on prostate cancer screening. Due to the controversy in evidence-based recommendations, PSA and/or digital rectal exam screening should be offered on a case-by-case basis. Societies that do recommend prostate cancer screening suggest beginning screening around age 40-50.

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) has historically been used as a screening test, in which concern for cancer arises in large or acute changes in number. If the cancer has invaded, then alkaline phosphatase is often elevated as well.

A abnormal digital rectal exam should prompt a tissue biopsy regardless of PSA level. An abnormal digital rectal exam includes:

Asymmtery

Nodularity

Induration

Needle core biopsy guided by transrectal ultrasound is the standard for definitive diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Complications

Impotence and incontinence are very common complications with a radical prostatectomy.

Testicular Cancer

Testicular cancer is the most common solid malignancy in males between the ages of 15 and 35 (i.e. young men). It occurs more commonly in whites than African-Americans.

Testicular lymphoma is an overall rare cause of testicular cancer, but is found in older men, greater than 50 years of age. It can be a primary lymphoma arising from within the testicle or can be metastatic disease from other parts in the body.

The risk factors for testicular cancer include:

Cryptorchidism (both testicles are at risk)

Testicular cancer in contralateral testicle

Klinefelter syndrome

Correction of cryptorchidism does not remove the risk factor; it only allows for better surveillance.

The classifications of testicular cancer are determined by the histology and cell type by a pathologist and are divided into the following types:

Germinal cell tumors (95% of all testicular cancers)

Seminoma (35% of all testicular cancers)

Nonseminoma

Embryonal carcinoma

Yolk sac (endodermal sinus tumor)

Choriocarcinoma

Teratoma

Mixed germ cell tumor (40% of all testicular cancers)

Stromal cell tumors (non-germinal cell) tumors

Leydig cell

Sertoli cell

Testicular lymphoma

The most common clinical presentation of testicular cancer is a painless testicular mass. Other symptoms include:

Weight loss

Pain in lower abdomen, perianal area, or scrotum

Gynecomastia (usually associated with hCG tumor production)

Hyperthyroidism (TSH and hCG have similar homology)

Symptoms of metastasis

Cough or dyspnea (pulmonary metastasis)

Bone pain (skeletal metastasis)

Leg swelling (iliac or caval venous obstruction)

Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, GI hemorrhage (GI metastasis)

The evaluation of a testicular mass begins with an ultrasound, which will show a hypoechoic intratesticular mass if it is a cancer. The following studies may be needed in order to determine the histologic type and extent of disease:

CT/MRI of abdomen and pelvis

Measurement of serum tumor markers

Radical inguinal orchiectomy (biopsy and treatment)

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (due to high false negative rate of CT)

Trans-scrotal biopsy of the testis or a trans-scrotal orchiectomy should NOT be performed because a scrotal incision in the presence of testicular cancer may cause local recurrence and/or metastasis.

The three most important serum tumor markers for testicular cancer are:

Beta human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG)

Alpha fetoprotein (AFP)

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

Beta-hCG is the most common serum tumor marker elevated in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs) and is produced by embryonal carcinomas and choriocarcinoma.

Note: serum beta-hCG is also elevated in 15-25% of patients with seminomas.

Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) may also be elevated in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, but is essentially never elevated in seminomas. Therefore, seminomas can almost completely be ruled out in the setting of elevated AFP.

Serum tumor markers should be measured before and after any treatment modalities are performed, since they are more useful for detecting recurrence than for diagnostic purposes.

Treatment

Men with suspected testicular cancer undergo a radical inguinal orchiectomy for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Once an orchiectomy is performed, the cancer is staged by radiographic imaging (similar for seminomas and non-seminomas):

Stage I: No clinical, radiographic, or marker evidence of tumor presence beyond the testis

Stage II: Retroperitoneal adenopathy on CT scan or palpable retroperitoneal adenopathy with disease limited to lymph nodes below the diaphragm, normal serum tumor markers after orchiectomy

Stage III: Visceral involvement

For early stage seminomas, treatment is orchiectomy with or without chemotherapy and radiation therapy. For early stage nonseminomas, treatment is the same, but with retroperitoneal lymph node dissection.

The most common chemotherapy used to treat testicular cancer is BEP:

Bleomycin

Etoposide

Platinum-containing chemotherapy (most commonly cisplatin)

Urethral Strictures

Urethral strictures are narrowings of the urethra which may be secondary to:

Inflammation (e.g. urethritis, sexually transmitted infections)

Scar formation (e.g. post-infectious, post-kidney stone passage)

Trauma to the urethral area (e.g. repeated catheterizations)

Pelvic fractures

Prior surgeries (e.g. hypospadias correction)

Prostate cancer radiation

Congenital causes

Patients with a urethral stricture typically present with difficulty voiding which may lead to acute urinary retention if severe.

Urethral strictures are diagnosed through history and a physical exam which includes a retrograde urethrogram.

Urethral strictures are typically initially managed with:

Balloon urethral dilation is the most common therapy

Endoscopic urethrotomy (incision of the urethra)

Urethral stenting

Suprapubic catheterization if acute urinary retention is present

Urethral strictures that recur may be managed with:

Reconstructive urethral surgeries (e.g. perineal urethostomy)

Surgical flap or graft for urethroplasty

Urological Emergencies

Testicular torsions

The presentation of testicular torsion is usually an afebrile adolescent with acute onset of severe pain in a testicle, lower abdomen, or the inguinal canal. The following are the most sensitive and important physical exam findings:

Pain not relieved upon elevation of testicle (pain relieved in epididymitis)

Absence of cremasteric reflex

Testicular torsion results from maldevelopment and fixation between the enveloping tunica vaginalis and the posterior scrotal wall.

Since testicular torsion is a clinical diagnosis and a medical emergency, immediate surgical repair is indicated. Bilateral orchiopexy is usually done to prevent future occurrences on either side. There is a salvage rate of 80–100% if pain presented less than 6 hours.

The feared complication of untreated testicular torsion is venous thrombosis followed by arterial thrombosis and infarction.

Priapism

Priapism is a painful condition in which the erect penis does not return to its flaccid state within 6 hours, despite the absence of physical and psychological stimulation.

Causes of priapism include:

Hematological disorders (e.g. sickle cell disease or trait, G6PD, leukemia, thalassemia)

Neurological disorders (e.g. spinal cord lesions or spinal cord trauma)

Medications (e.g. intracavernosal injections for treatment of erectile dysfunction and trazodone)

Since priapism in patients with sickle cell disease is a low flow priapism due to occlusion of venous drainage with stasis and ischemia, the treatment is the following:

Aspiration of blood, followed by saline irrigation and injection of adrenergic agonist

If still refractory, blood exchange transfusion

Surgical intervention (only considered if priapism lasts >12 hours)

The treatment of priapism not associated with sickle cell disease centers around intracavernosal phenylephrine.

Pyelonephritis

Acute obstructive pyelonephritis (also called febrile renal colic) is an infection of the kidney with co-occurring obstruction which is an urological emergency and can lead to rapid renal failure and potential sepsis.

The usual presentation of acute obstructive pyelonephritis starts as colicky lumbar pain (i.e. renal colic) that suddenly develops into chills, acute high febrile spikes, and flank pain.

Diagnosis of acute obstructive pyelonephritis is made by non-contrast abdominal CT (may or may not show stone depending on stone composition) and renal ultrasound, which will show urinary tract ectasia or hydronephrosis.

Since acute obstructive pyelonephritis is an urological emergency, immediate treatment is indicated requiring:

Drainage of the urinary tract via ureteral catheterization or percutaneous nephrostomy

IV antibiotics

Last updated