09 Colorectal

Acute Abdomen

The definition of acute abdomen is the sudden onset of severe abdominal pain usually due to peritoneal inflammation.

The differential diagnoses of acute abdomen is wide and highly dependent on the clinical history. Some highlights include 4 "-itis" pathologies and the "three 3's":

4 -itis's: Appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis

3 miscellaneous GI: Small bowel obstruction, peptic ulcer disease, GI perforation

3 reproductive: Ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, ovarian torsion

3 cardiovascular: Myocardial infarction, mesenteric ischemia, AAA rupture

Since abdominal pain is the primary complaint of acute abdomen, characterization of the pain is the most important part of the HPI (history of present illness). The following questions should be asked:

Where is the pain localization? (e.g. RLQ- appendicitis, LLQ- diverticulitis, RUQ- cholescysitis)

Does the pain radiate? (e.g. cholecysitis- right scapula, pancreatitis- back)

What makes the pain worse (i.e. precipitating factors)? (e.g. eating- mesenteric ischemia)

What makes the pain better (i.e. relieving factors)? (e.g. fetal position- peritoneal inflammation)

What are the associated symptoms?

Medical history(e.g. atrial fibrillation- mesenteric ischemia, STDs- pelvic inflammatory disease)

Surgical history (e.g. past abdominal surgery- adhesions/small bowel obstruction)

Symptoms

The common symptoms of acute abdomen include:

Pain

Fullness, bloating

Nausea/vomiting

Dyspnea (due to decreased diaphragmatic excursion)

Fever

Treatment

The treatment for most causes of acute abdomen is surgery. However, the following are causes of acute abdominal pain that do not require surgery:

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Diverticulitis (sometimes)

Sickle cell crisis

Psychological

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Pancreatitis

Anus

Fissures

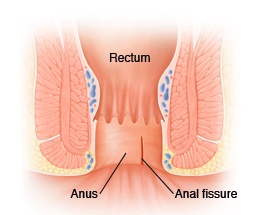

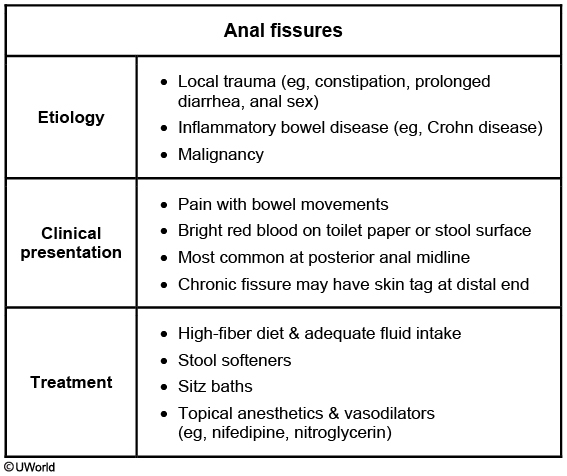

Anal fissures are linear tears in the anal mucosa below the dentate line, most commonly found in the posterior midline.

Anal fissures typically occur in the setting of repetitive local trauma (e.g. childbirth, repetitive constipation/diarrhea, anal sex).

Patients with an anal fissure typically present with:

Blood on the toilet paper following defecation

Pain

First line therapy for an anal fissure is conservative therapy (e.g. sitz baths, fiber, lidocaine, stool softeners).

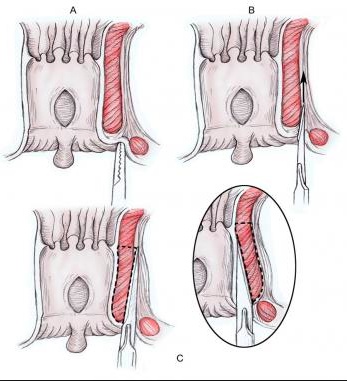

If conservative therapy fails in the management of an anal fissure, a lateral internal sphincterotomy or botulinum toxin injection may be beneficial.

Crohn's

Crohn’s disease should be suspected in cases when an anal fissure, perianal abscess, or an anorectal fistula fails to heal.

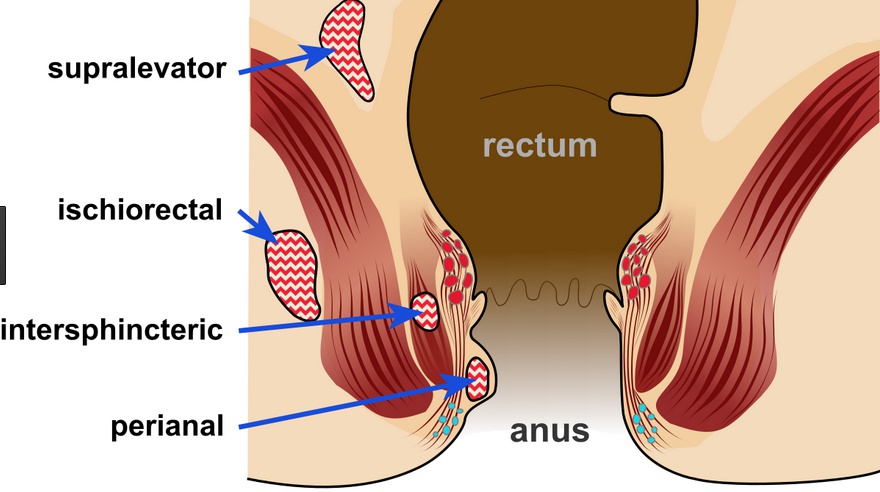

Abscesses

Perianal abscesses (aka anorectal abscesses) are caused by an obstruction of an anal crypt gland, resulting in bacterial overgrowth and abscess formation.

Risk factors for a perianal abscess include:

Constipation

Diarrhea

Inflammatory bowel disease

Immunosuppression or chemotherapy

Diabetes mellitus

Patients with a perianal abscess typically present with:

Severe anal or rectal pain not associated with bowel movements

Fever

Malaise

On physical exam, a patient with a perianal abscess typically displays:

A fluctuant mass

Overlying erythema, usually including the surrounding area

Purulent drainage

Perianal abscesses are treated by incision and drainage.

Poorly managed diabetics are predisposed to necrotizing tissue infections from a perianal abscess.

Fistula

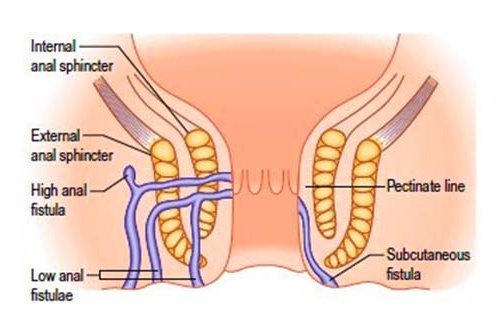

An anorectal fistula is a tract from the rectum to the perianal skin, most commonly due to reepithelialization of a ruptured perianal abscess.

Risk factors for developing an anorectal fistula include:

Perianal abscesses (most common cause)

Inflammatory bowel disease

Local radiation

Foreign bodies

Patients with an anorectal fistula typically present with:

Perianal drainage of fecal or purulent material

Itching

Intermittent pain

The diagnosis of an anorectal fistula relies upon visual inspection of an anorectal tract. A probe may be used to confirm the presence of a tract.

Anorectal fistulas are treated preferentially with a fistulotomy.

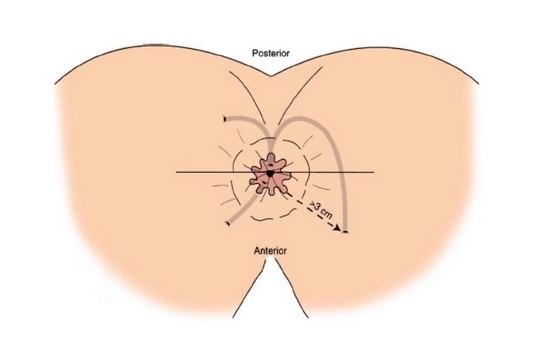

Goodsall’s rule is used to facilitate a surgical plan:

Anterior fistulas connect with rectum in a straight line

Posterior fistulas go towards a midline internal opening in the rectum

Anorectal fistulas that diverge from Goodsall’s rule should raise suspicion of Crohn’s disease.

Cancer

Anal cancer is an uncommon form of cancer. Risk factors for its development include:

Anal intercourse

Multiple sexual partners

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infections (16 is the most common subtype)

HIV

Immunosuppressive therapies

Smoking

Anal cancer is most commonly of the squamous cell carcinoma histological type.

Patients with anal cancer typically present with:

Bleeding

Feeling of perianal fullness

May be asymptomatic

Anal cancer is definitively diagnosed with a biopsy and CT or MRI imaging is used for staging.

The initial treatment for anal cancer is chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin (aka modified Nigro or Wayne State protocol).

Anal cancer refractory to chemoradiotherapy should be treated with abdominoperineal resection as indicated.

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids are dilations in the rectal and anal veins. The two types of hemorrhoids are:

Internal hemorrhoids which are dilated veins of the superior rectal plexus, located above the dentate line

External hemorrhoids which are dilated veins of the inferior rectal plexus, located below the dentate line

Internal hemorrhoids are lined by columnar epithelium,whereas external hemorrhoids are lined by squamous epithelium.

Some of the most important risk factors for developing hemorrhoids are prolonged sitting, constipation, and pregnancy. Other risk factors for developing hemorrhoids include:

Increased age (tissue scaffolding weakening)

Portal hypertension

Pelvic tumors

Patients with hemorrhoids typically present with:

Hematochezia

Rectal prolapse

Itching

Sense of fullness in the anorectal region

Acute pain from thrombosis (only if external, because of somatic innervation)

The first line therapy for hemorrhoids is conservative therapy such as sitz baths, stool softeners, OTC remedies and a high fiber diet.

Hemorrhoids refractory to conservative management may be managed surgically. Indications for surgery also include thrombosed or necrotic external hemorrhoids. Surgical management depends on the type of hemorrhoid:

Internal hemorrhoids: Rubber band ligation

External hemorrhoids: Hemorrhoidectomy

If left untreated, hemorrhoids may:

Strangulate leading to gangrene

Thrombose

Bleed leading to iron deficiency anemia

Inguinal Hernia

Inguinal hernias are classically categorized based on location:

Indirect inguinal hernias occur lateral to the inferior epigastric artery, “indirectly” entering Hesselbach’s triangle

Direct inguinal hernias occur medial to the inferior epigastric artery, “directly” entering Hesselbach’s triangle

The boundaries of Hesselbach’s triangle are:

Inguinal ligament inferiorly

Inferior epigastric artery laterally

Rectus abdominus muscle medially

An indirect inguinal hernia is caused by the failure of the processus vaginalis to close, allowing intestines to enter the inguinal canal.

Direct inguinal hernias are usually caused by inguinal canal floor weakness.

Indirect inguinal hernias are covered by all 3 layers of spermatic fascia (i.e. external spermatic fascia, cremasteric fascia, and internal spermatic fascia), whereas direct inguinal hernia sacs are covered by only the external spermatic fascia.

Risk factors for an inguinal hernia include:

Prior history of groin herniation

Caucasian

Elderly

Male

Previous abdominal wall surgeries

Anything that causes increased intra-abdominal pressure

Connective tissue abnormalities

Patients with an inguinal hernia typically present with:

Heaviness in the groin mostly at times of increasing intra-abdominal pressure (e.g. weight lifting)

Pain in the groin or testicles (if incarcerated or strangulated)

Changes in bowel movements

Asymptomatic

The diagnosis of an inguinal or femoral hernia is based upon physical exam, and when in doubt of the location, an ultrasound may be useful.

On physical exam, patients with an inguinal hernia typically have:

A reducible bulge in the groin if unincarcerated

An irreducible bulge in the groin if incarcerated

Increased size of bulge with coughing or Valsalva

The definitive treatment for inguinal hernias is surgery; however, for patients with no symptoms and an easily reducible hernia, watchful waiting is appropriate.

If left untreated, an inguinal hernia may become:

Incarcerated (irreducible bulge, not always strangulated)

Strangulated (systemic (e.g. fever, nausea, vomiting) and local (e.g. erythema, painful to palpation) signs and symptoms may be present)

Necrotic

Other Hernia

Femoral hernias anatomically occur through the femoral ring, which is the most medial aspect of the femoral sheath, lateral to the lacunar ligament, and inferior to the inguinal ligament.

Femoral hernias are typically acquired secondary to aging or injury.

Richter’s hernia occurs when only half of the intestinal wall is protruding, seen commonly in femoral and obturator hernias.

Littre’s hernia describes a hernia sac that contains Meckel’s diverticulum. (Think “Littreckel”)

Garengoff’s hernia and Amyand's hernia describe femoral and inguinal hernia sacs, respectively, that include the appendix.

A pantaloon hernia describes a combination of a direct and an indirect inguinal hernia. (The hernia is divided by the inferior epigastric vessels so that it is reminiscent of a pair of pantaloons)

Spigelian hernia describes a hernia sac passing through the spigelian (aka semilunaris) fascia. (Think of Smeagol, sounds like SPIGELian, standing in front of the moon, semiLUNAris fascia)

Cooper’s hernia describes a femoral hernia with two sacs, the first being in the femoral canal, and the second passing through a defect in the superficial fascia and appearing immediately beneath the skin.

An incisional hernia describes a hernial sac passing through a previous surgical incision, associated with obesity, diabetes, and infection.

Large Bowel Obstruction

Large bowel obstruction is a mechanical or functional obstruction of the large intestine.

The etiologies of large bowel obstruction include:

Colon cancer (primary concern)

Hernias

Adhesions

Volvulus

Diverticulitis/Diverticulosis

Inflammatory bowel disease

In severely ill patients, acute dilation of the colon can occur in the absence of any actual mechanical obstruction. This pseudo-obstructive phenomenon is known as Ogilvie syndrome.

Symptoms include constipation, abdominal discomfort, and feculent emesis.

On physical exam, the abdomen may be distended, tympanitic , and tender.

Diagnosis can be made with abdominal x-ray or CT imaging. Multiple air-fluid levels and dilated air-filled proximal colon with air-absent distal colon is highly suggestive of LBO. The clinician should also be vigilant to look for any masses.

Other pertinent studies to evaluate for the presence and/or cause of obstruction may include contrast enema or sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy.

Treatment is aimed at relieving the obstruction by enema, decompression with a rectal tube, or colonoscopy. In severe cases, surgery may be required.

Small Bowel Obstruction

The most common causes of small bowel obstruction are:

Adhesions from prior abdominal surgery (most common cause in US)

Hernias (most common cause worldwide)

Cancer

Other less common causes of small bowel obstruction include:

Appendicitis/diverticulitis/intraabdominal abscess

Intussusception

Volvulus

Crohn's disease

Congenital stricture

Traumatic intramural hematoma

Gallstone

Symptoms

The most common presenting symptoms of small bowel obstruction (SBO) are:

Nausea

Vomiting

Abdominal pain

Obstipation

The severity of the symptoms of SBO can vary depending on the location of the obstruction. Nausea and vomiting are prominent in proximal obstruction, whereas abdominal pain and distention is more severe in distal obstruction.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) is usually diagnosed based on history and physical examination. Physical examination may show any or all of the following:

Signs of dehydration (e.g. tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, decreased urine output)

High-pitched "tinkling" and hyperactive bowel sounds (though they may be later reduced/absent)

Abdominal tenderness and/or distention

Abdominal mass related to cause (e.g. tumor, hernia, volvulus)

Diagnosis

Complete blood count with differential (CBC with diff) and basic metabolic panel (BMP) are the most common laboratory studies ordered and are not specific or sensitive for SBO, but are used to identify possible complications. The results show any or all of the following:

Hypovolemia

Leukocytosis

Hyponatremia or hypokalemia

Elevated lactate (not part of CBC or BMP, but sensitive for acute intestinal ischemia)

Anemia (cancer or Crohn's disease)

Note: In patients with chronic small bowel obstruction, such as from Crohn's disease or slowly progressing tumors, no lab abnormalities may be present.

Imaging is used to identify the location, partial vs. complete obstruction, and the possible cause. Plain abdominal x-ray films may show dilated small bowel loops with multiple air-fluid levels and lack of gas in the colon. CT scans have utility when high clinical suspicion remains despite negative or relatively unremarkable radiograph.

Treatment

Management of small bowel obstruction requires volume resuscitation, electrolyte abnormality corrections, and determining if surgery is necessary. Surgery is required for complete obstruction and for clinical or radiographic signs of ischemia, necrosis, or perforation.

Non-operative management should be attempted if signs of a complete or complicated obstruction are absent. Management includes:

Bowel rest by making the patient NPO

Nasogastric suctioning to decompress the bowel

IV fluids to maintain electrolytes and hydration

Last updated